My 2024 in Reading (Plus Lessons from Tokarczuk's Prose)

A look back on the books I read in 2024 and some thoughts on Olga Tokarczuk's The Empusium

Like many, I keep a simple log of all the books I read and like to look back on my reading at the end of the year. Before I get to that, I wanted to talk a little bit about the last novel I read—Olga Tokarczuk’s The Empusium—because I thought it was a great example of the kind of prose I advocated for in my Substack essay “Turning Off the TV in Your Mind.”

The article was about how a lot of contemporary American fiction reads as if the writer is transcribing TV scenes they see in their mind rather than embracing the full possibilities of prose. TV and film will always produce the best TV and film. Novels should embrace the qualities novels excel at, I say. Counter Craft readers seemed to really enjoy that essay, but a few of you asked for specific examples. So, when I read Tokarczuk’s The Empusium I photographed a few examples that fit the topics I’d brought up.

I did have some issues with The Empusium—mainly that the novel felt aimless in the middle and how some of the themes felt heavy-handed and somewhat disconnected from the plot—but the prose was captivating and the translation, by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, expert. There were also some lovely horror moments and fairy tale vibes. But let me get to the examples of Tokarczuk’s prose. The novel employs a flexible third-person POV that is at times a close third on the main character (i.e., we are in the mind of the character), at times the commenting voice of a classic omniscient narrator, and at times a mysterious “we.” Here’s the opening:

This is a great example of prose that does not read like aspiring visual media. It establishes a narrative voice with a POV, one that will comment on the proceedings not merely transcribe them (“stalks of feeble little plants—a space trying at any cost to keep order and symmetry”). The prose takes its time to guide the reader into the book, not even revealing the main character’s name on the first page or worrying about starting “in media res.” This opening also allows Tokarczuk to set up some of the novel’s themes and the atmosphere, the latter quite important to a horror novel. (The book is subtitled “a health resort horror story.”) Granted, Tokarczuk recently won the Nobel Prize and so has far less pressure to cater to the markets than most of us. But this prose is more interesting, to me at least, than what you expect from the average “TV prose” opening. A little later the section closes this way:

(Sorry for the blurry pic.) Here, we see the flexibility of the POV as it can accesses both Wojnicz’s feelings and provides the peculiar “we.” Initially, this “we” seems to be the author guiding the reader along in that arm-on-the-shoulder way. “Dear reader, let us examine this now together...” Yet here the reader begins to realize that the “we” are entities of some sort, a mystery that will help drive the book. I won’t spoil that here. Obviously, a movie could show us these details. A camera shot could move through smoke and zoom into cracks in the floorboards. But it is the POV and the commentary that makes this prose.

Another moment from later in the book:

In my piece, I made the argument that “TV prose” fails to summarize. Instead, scenes play out in “real time” and show the reader every action and every spoken dialogue. The above is a quick and nice example of how prose can easily speed up time, skip around, and summarize. Specifically, I’m referring to the line In a few sentences, Wojnicz explained his family history. Many authors would quote that dialogue in full, but why? The reader doesn’t need the information repeated and summarizing helps the pacing and dark humor of the doctor’s response.

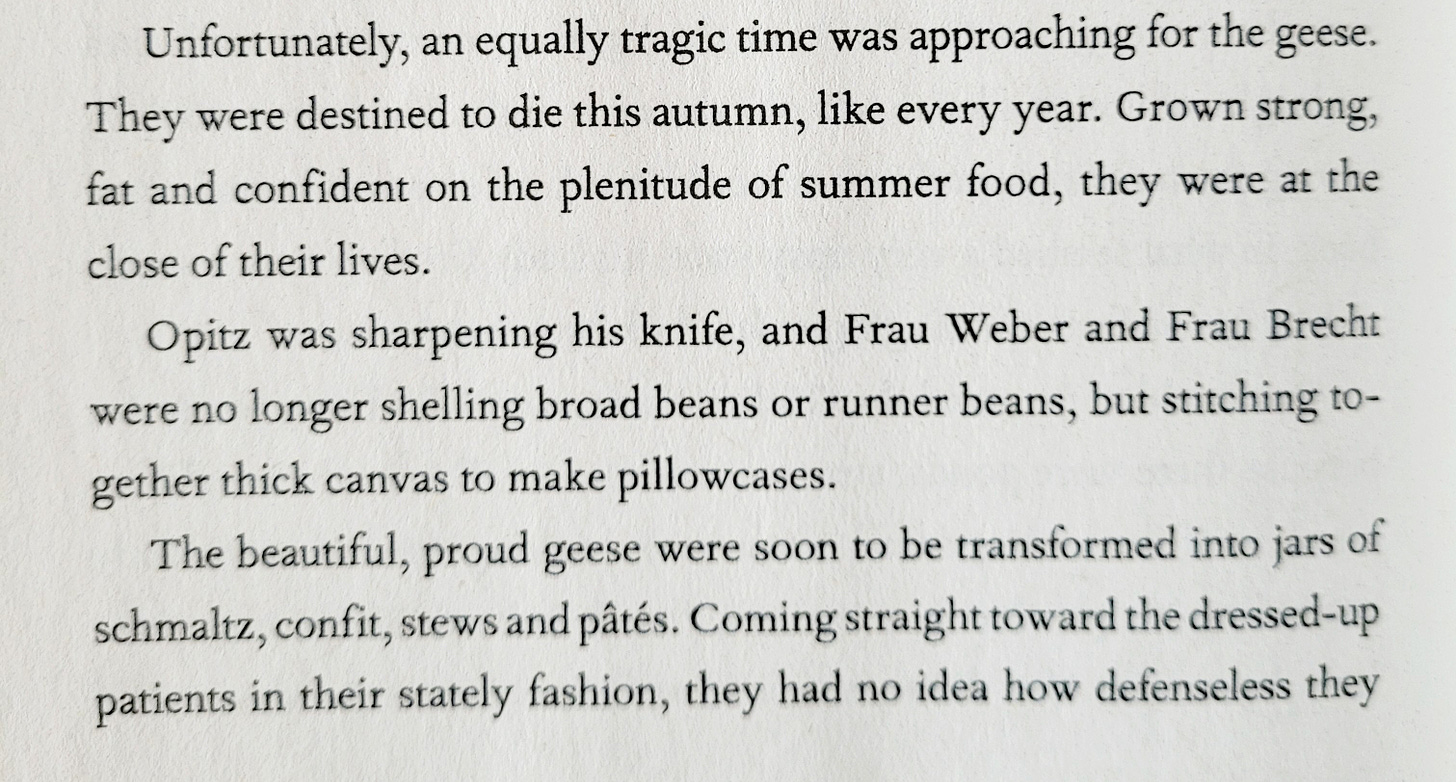

Lastly, I talked a lot in the article about interiority. Interiority is vital to first person and close third prose, and not something that film and TV can easily access. It is an advantage of prose. But I should have included a bit about how omniscient third allows for a kind of commentary that is also an advantage of prose. (Again, visual media has its own advantages that prose has a hard time replicating.) This description of geese would be hard to pull off in film:

My 2024 in Books

Okay, onto my 2024 in reading books. As I said, I keep a very simple count of books I read in a year. My rules are simple: 1) I only include books that are published or in galleys (i.e., no counting drafts of friends’ works-in-progress) and 2) I count any book I finish in the year I finish. I sometimes stretch books across multiple years, even many years in the case of short story collections, so only count them in the year I finish. I figure it all works out in the wash over time.

In this count, I read 53 books in 2024. Fewer than I’d like, though my reading time was more constrained than normal since I was deep in edits on my novel Metallic Realms—forthcoming in May 2025! Preorder here!—as well as working full-time. (Oh why pretend? I wasted too much time online as always…) I did my best reading of the year when I made a vow to put my phone away and just read before bed. I never once regretted doing so, even though the pull of the phone is always there. A 2025 resolution will be to read even more and scroll even less.

When I was younger, I made a conscious point to track the diversity of my reading throughout the year to make sure I was reading a good balance of genders, world literature, and genres (both in the sense of fiction genres and in the sense of types of books like non-fiction, poetry, etc.). I don’t do so anymore, which makes it nice to look back and see what I “naturally” gravitated to in a given year. For 2024, my gender split ended up nearly 50-50. 52% women, one non-binary author, and one multi-author anthology. A strong majority (58%) were translated, mostly Japanese and Spanish though also Polish, Danish, French, and others. I read almost exclusively fiction with only 13% non-fiction. I hope to improve on that in 2025.

Some of these books were old favorites I was rereading, often to teach. Five that really stood out on a reread:

The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter (I wrote about that book and Carter’s “So Fucking What?” approach here.)

Chronicle of a Death Foretold by Gabriel García Márquez (What can one say? Márquez is simply a master.)

The Mezzanine by Nicholson Baker (I wrote about that and “The Novel as Shaggy Dog Joke” here.)

Revenge by Yoko Ogawa (I read three Ogawas this year, but Revenge remains my favorite.)

Multiple Choice by Alejandro Zambra (A novel as standardized test. I remain amazed at Zambra’s commitment to the form and ability to pull emotion from it.)

Among new books, I interviewed many of the authors whose 2024 releases grabbed me in my “Processing” series or wrote about the books in other posts. So click on those if you’d like. I’ll add one more 2024 recommendation: Opacities by Sofia Samatar. This is a lovely and thought-provoking collection of quotes, anecdotes, and musings on the literary life. It would interest and inspire any author, I think.

In terms of new-to-me-but-published-before books that stood out, I wrote about The Palace of Dreams by Ismail Kadare and The Factory by Hiroko Oyamada already in this post. Both have lingered in my mind despite being in some ways flawed. Other older books that grabbed me this year were Vladimir Nabokov’s The Luzhin Defense—like Marquez, Nabokov is simply a genius who can grab my attention writing about any subject—and, to pick a non-fiction book, The Anarchy by William Dalrymple about the British East India Company’s fascinating and horrifying colonization of much of India. Lastly, I’ll recommend The Taiga Syndrome by Cristina Rivera Garza (translated by Aviva Kana and Suzanne Jill Levine), which is a lush and dark fever dream of a detective novel.

If you missed my 2024 round-up of what I wrote, you can read that here. And the Goodreads giveaway for my forthcoming Metallic Realms is still going on if you’d like to enter. Of course, it is available for preorder too. That’s it for 2024. See you in 2025 to talk more about weird books, writing craft, and other literary sundries.

If you enjoy this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout—which The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent”—or preorder my forthcoming weird-satirical-science-autofiction novel Metallic Realms.

If you liked The Palace of Dreams try out Kadare’s The File on H, I liked it even more. A fictional retelling of two scholars who go in search of the origins of oral epic poetry to answer the “Homeric question.”

That “writing like TV” business— i heard an interview with Nick Mamatas where he gave the impression this problem is an epidemic.