Turning Off the TV in Your Mind

Thoughts on flipping from "TV brain" to "prose brain" when writing fiction

[2/12/25 note: since this essay is being shared around, I will quickly note there is currently a Goodreads giveaway for my new novel, Metallic Realms, underway. The novel was just named one of the 20 most anticipated books of 2025 by Esquire. For more info or to preorder (always deeply appreciated!) click here.]

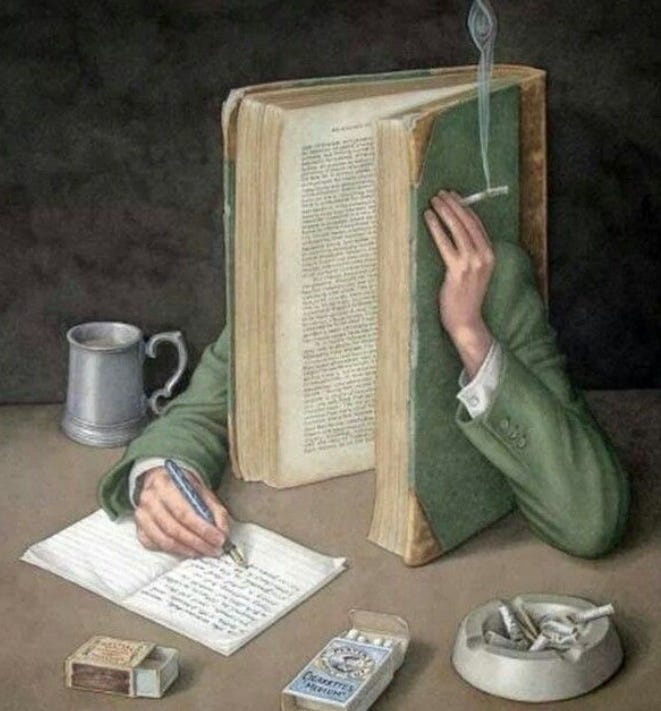

I am not a neuroscientist, but learning an artform changes your brain. Or at least it changes how you think. To learn to photograph, you learn to think in angles and apertures. To learn to paint, you begin to think in brushstrokes and pigments. And to learn to write fiction, you start to think in sentences, POV, and other aspects of narrative prose. This takes a lot of time. Time studying and time practicing. No, there never are any shortcuts there.

This applies within mediums too. Thinking in fairy tales is different than thinking in hardboiled detective fiction. Thinking in aphorisms is different than thinking in longform essays. So on and so forth. (This is likely why so many artists can excel in one area but struggle in adjacent ones. Short story writers who can’t finish novels. Actors who flop at directing. Etc.) Probably all this is obvious, but I was—sorry—thinking about this after discussing a few issues in contemporary fiction that all seem to add up to the same thing: novelists thinking not in prose but in TV.

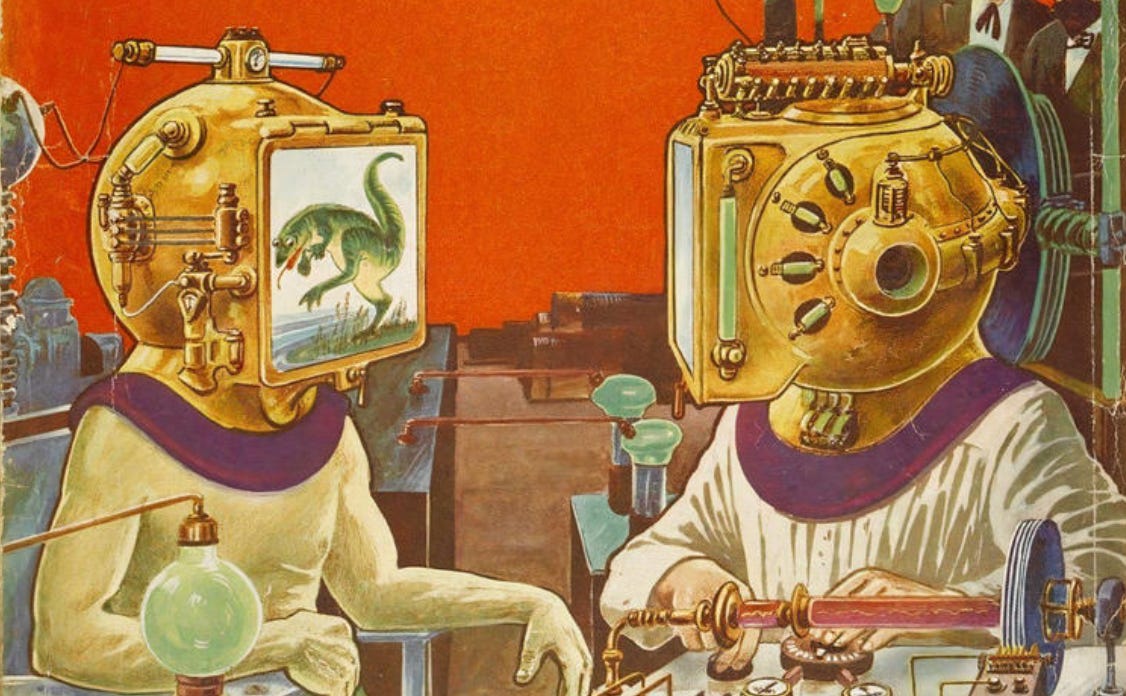

I’m using “TV” as a shorthand for any visual narrative art from feature length films to video games. A lot of fiction these days reads as if—as I saw Peter Raleigh put it the other day, and as I’ve discussed it before—the author is trying to describe a video playing in their mind. Often there is little or no interiority. Scenes play out in “real time” without summary. First-person POV stories describe things the character can’t see, but a distant camera could. There’s an overemphasis on characters’ outfits and facial expressions, including my personal pet peeve: the “reaction shot round-up” in which we get a description of every character’s reaction to something as if a camera was cutting between sitcom actors.

Some may argue these trends are the result of hammering “show don’t tell” at young writers or else the fact novelists increasingly write with Hollywood adaptations in mind. Perhaps both are factors. (Although in my limited experience, Hollywood options are about premise more than prose. If Wolfnauts gets adapted, it is because “GRAVITY meets TWILIGHT but with werewolves!” is an elevator pitch that wins over studio executives and screams sequel potential. OTOH, the quiet Künstlerroman A Portrait of a Millennial Author Ambling Around Brooklyn is probably not being adapted no matter how cinematic the scenes are written.)

My theory is that we live in the age of visual narratives and that increasingly warps how we write. Film, TV, TikToks, and video games are culturally dominant. Most of us learn how stories work through visual mediums. This is how our brains have been taught to think about story. And so, this is how we write. I’m not suggesting there is any problem in being influenced by these artforms. I certainly am. The problem is that if you’re “thinking in TV” while writing prose, you abandon the advantages of prose without getting the advantages of TV. Visual media and text simply work differently and have different possibilities and constraints. I don’t believe in rules for art. But I believe in general principles. One is that it’s typically best to lean into the unique advantages of the medium you are working in. A novel will never beat good TV at being TV, but similarly TV will never beat a good novel at being a novel.

Perhaps the dominance of visual narrative forms means that readers simply want prose that reads like TV and I’m simply in “old man yells at cloud” territory. But then, I am an old man, or at least have the gray hair of one. And I think the risks of “TV brain prose” are ones we all face. Even most published novelists—and I include myself here—consume more visual narratives than prose narratives, which makes it harder to switch on your “prose brain” when writing.

So, how do you think in prose instead of TV? First, adjust your inputs. Read more and watch less. Study great books and look at how the masters deploy diction, details, syntax, and structure. In your own writing, pay attention to sounds and sentences. How information is ordered and how a reader will experience a story word by word and paragraph by paragraph. Those are the most important things, but also the vaguest. Here are some more specific tips:

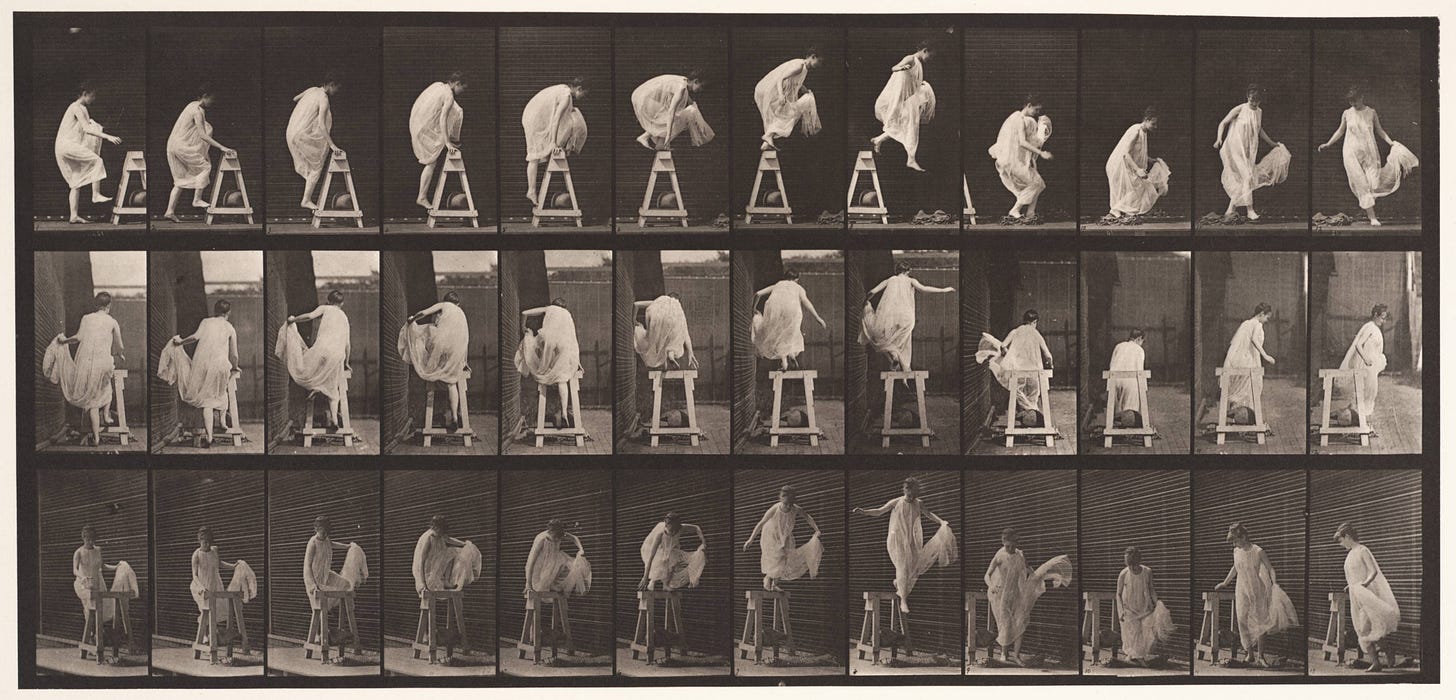

Avoid Describing Every Single Movement

One might assume that what “TV prose” losses in depth it would make up for in speed. That the stripped-down text would move at a quicker pace, perhaps one more geared to the modern short-attention-span mind. Perhaps, in theory. But in practice, TV brain prose can be more cluttered with filler sentences because writers describe more than they need to. The occasional montage aside, most TV scenes play out in real time. If a character gets a glass of water, they perform every movement—opening the cabinet, pulling out the glass, turning on the faucet, filling the glass, etc. So, writers who are jotting down a TV scene in their mind likewise enumerate these actions. “Farah got up and walked over the cabinet, reached inside, and withdrew a tall glass. She then turned on the faucet and filled the glass. She took a sip.” Such banal movements are tedious in prose. Unless there is a point to the tedious description—I dunno, this is a Martian carefully studying human movements?—a simple “she got a glass of water” is probably all you need.

Remember too that actors perform small actions that have may have no real effect in a given scene because it would be boring to watch actors stand still arms at their side while delivering lines. Movement, even pointless movement, has a use in visual media. We like to watch actors do things. Prose is different. In prose, you can simply skip all the pointless actions. You can write just the dialogue, or fill space between dialogue with interiority, setting description, flashbacks, or whatever you want. Perhaps you don’t need even “she got a glass of water” unless that detail is important for the plot, themes, or characters.

Remember Written Characters Don’t Have Actors

Two advantages that visual media has over text are 1) human faces and bodies are inherently interesting (see above) and 2) the eye can process large amounts of visual information near-instantaneously. We take in a TV frame much quicker than a full page of text. One feature of TV prose is a lot of attention paid to the things that your eye notices on TV such as actors’ faces and outfits. But there are no actors on the page. Your prose is—for better or worse—only words.

Watching your favorite actors cheer and clap for 2 seconds on TV works differently than reading two whole paragraphs of “Ross clapped and then pumped his fists. Chandler jumped and slapped Joey’s shoulder. Monica…” And that’s before getting into the actor’s outfits, which would also take much longer to describe in prose than to see. Sometimes there will be a reason to describe a character’s clothes at length—I always think of American Psycho’s brand-name laden outfit descriptions, which play into the novel’s theme of vapid consumerism—but normally it is better to be selective with your character details in prose. One to three repeated visual details might better conjure a character in the reader’s mind than an item-by-item and feature-by-feature list that in prose will likely be confusing and quickly forgotten.

You Are the Lord of Time

Above, I described areas where visual media has an advantage on prose. Here’s an example of where prose has an upper hand: the author can completely manipulate time. Want to speed through a long argument? You can summarize it in a sentence or two (they argued for hours, growing drunker as the sun slipped away). Want to slow down time? You can write an entire novel that takes place in the span of an escalator ride. You can skip past a century in a sentence or stretch out a second for pages and pages.

While visual information is processed together and quickly—we take in the entire frame or canvas more or less at once—textual information proceeds word by word and line by line. This gives the author great power at controlling the “speed” of any given action or scene. In text, we can dip in and out of scene between long passages of interiority (or vice versa) in a way that film just can’t. Yes, a TV show can do a freeze frame or use a montage. But these methods are cruder than the myriad complex ways that prose can control time. If you are prone to writing real-time, film-type scenes, then in revision look and see if the story needs all the action and dialogue you put down in the first draft. If something is boring or not doing enough work for the story, it can probably be cut or summarized.

Interiority, Interiority, Interiority!

When I talk with other creative writing professors, we all seem to agree that interiority is disappearing. Even in first-person POV stories, younger writers often skip describing their character’s hopes, dreams, fears, thoughts, memories, or reactions. This trend is hardly limited to young writers though. I was speaking to an editor yesterday who agreed interiority has largely vanished from commercial fiction, and I think you increasingly notice its absence even in works shelved as “literary fiction.” When interiority does appear on the page, it is often brief and redundant with the dialogue and action. All of this is a great shame. Interiority is perhaps the prime example of an advantage prose as a medium holds over other artforms.

Prose allows free and complete access to character’s minds in a way you can’t really get with film. Other than voiceovers, film is largely constrained to conveying character by action and dialogue. Even memory is typically rendered by action and dialogue via flashbacks. Prose can do all those things and far more. Stream-of-consciousness, free indirect speech, filtering details through POV, exploring a character’s thought process, etc. We can have it all in fiction. That’s no little thing. We all live our existences inside our minds. The interior world is at least as large as the exterior one.

TV prose does tend to include some interiority. But there is, in my reading, typically little investment in the interiority and what is provided is often redundant with the action and dialogue. Sarah stared at Tim’s luscious lips. God, I hope he kisses me, she thought. “Kiss me already,” she said, leaning close. The second sentence doesn’t tell us anything new. If this is the kind of interiority you’re offering, well, little is lost by cutting it. But interiority it is an ideal spot to complicate the story and deepen the characters. If Sarah thinks something that subverts or rearranges our understanding of the scene—or even explores her hopes and fears beyond a basic repetition of the information we have—that’s much better.

POV Isn’t a Camera on the Wall

My last suggestion is to remember that POV isn’t a camera. A camera is in some sense “objective,” showing us everything in frame. But POV is subjective, and everything should be filtered through a character’s subjectivity. (Caveat: Yes, there is the “camera on the wall” Third Person Objective POV… but there is a reason that’s rare.) Let’s assume you are writing in first person or close third. If Raúl is describing Gunther’s green sweater, ideally the description is filtered through Raúl’s mind and tells us about his character as well as Gunther’s sartorial choices. It shouldn’t be a dry and neutral description—Gunther was wearing a green cable knit cotton-Merino blend sweater from The Gap—but a description from Raúl’s POV. Maybe Raúl thinks the sweater is the kind of goddamn ugly sweater Gunther always wears, that fool. Or maybe he thinks it is gorgeous and now he’s embarrassed to go out to the club in his dingy moth-eaten sweater like some dork-ass loser. Similarly, such details should make sense for what the character would notice. TV prose often has neutral but also overly specific visual details where we are told the make and model of car the drives by, say, or the type of fabric used in every item of furniture. Can you tell that when you walk into a stranger’s home? Unless Raúl is really into sweaters, is he likely to recognize what is a cotton-Merino blend? Or tell what specific brand a sweater is? Doubtful.

Okay. Once again, what I thought would be a short post is giving me a “Near email length limit” warning. I’ll stop here. I know that most of the above is somewhat obvious. But I find these points useful to remember, especially when revising my work. The main thing is that prose is not film. Text functions differently, with different possibilities and limitations. My advice is always to lean into what the medium you are working in does best. And, of course, read, read, and read, then write, write, and write.

In personal news, I have a little fairy tale called “Sleeping Beauty and the Restless Realm” up at Lightspeed. I’m quite happy with this one, and it’s short (under 1,000 words) if you are looking for a quick read while you have a snack.

As always: If you enjoy this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout—which The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent”—or preorder my forthcoming weird-satirical-science-autofiction novel Metallic Realms.

I've noticed that a good day of writing is when I get this exact thing right the first time, and that the majority of my editing is "de-TV-ifying" my drafts.

There's a great bit in "Understanding Comics" where Scott McCloud says that - paraphrasing here - it takes fewer panels to depict the creation and destruction of the known universe in a comic book than it does to depict a person blinking. (I bring up McCloud's work a lot because it was genuinely life-changing for me as a teen, but it really is applicable here! One of those books has an entire chapter about word + image combos that makes almost the same point that this post does about redundancy: a picture of a smirking guy jabbing his finger, saying "I jab my finger at you!," captioned "He jabbed his finger!")

Anyway! As always I will say "TV innocent ;-)" - or rather, it's worth noting that good TV writing can do all the stuff you mention in this post on a mechanical level, and that aspiring novelists could learn a lot by thinking about those aspects and applying them to their writing. E.g., so much of cinema is built around the question of "when and why and on what image do we cut to the next shot/scene?", which is something authors... I mean, maybe you ask that question! But you don't *have* to ask that in the same way a good filmmaker does, and I wonder if novels would be better if novelists regularly asked themselves questions like that.