Angela Carter and the "So Fucking What?" Approach to Writing

Recommending The Bloody Chamber for your October reading pile

Last week, I was rereading and researching Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber to teach and came across this quote: “Okay, I write overblown, purple, self-indulgent prose. So fucking what?” Carter said this in a BBC interview, and it epitomizes what makes The Bloody Chamber such a unique and thrilling read. She does what she wants in those stories and doesn’t stop to worry about who will call it too indulgent, too overblown, too unlikable, or anything else. It’s also just a nice sentiment to hear in the social media era when so so many writers seem to spend their time fretting about “the rules” or trying to write for their worst readers at the expense of their best ones.

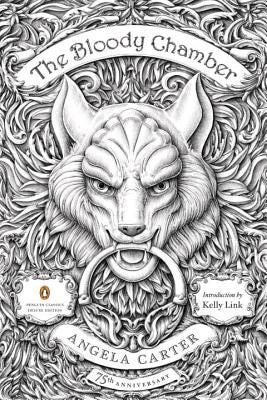

If you haven’t read The Bloody Chamber, it’s a perfect little book of dark stories to add to your Halloween reading list. The Bloody Chamber is typically described as book of feminist fairy tale retellings, although it’s a bit looser than that. The first few stories are recognizable as retellings of classic fairy tales like “Beauty and the Beast,” but Carter also includes a couple stories that aren’t based on fairy tales such as the vampire story “Lady in the House of Love.” In my reading, it is more of a Gothic horror / fairy tale mash-up collection—to the degree such labels are useful. I mean this pretty literally. The last three stories, for example, are all combinations of werewolf stories and “Little Red Riding Hood.”

This is already one way Carter is following her instincts rather than what might seem proper. Many writers sitting down to produce a collection of fairy tale retellings would first survey traditional fairy tales and try to find a representative samples of stories that cover different tropes and topics. One story about a princess in a castle. One story about the dangers of the dark woods. Etc. Carter, instead, writes three werewolf / “Little Red Riding Hood” tales, two (and arguably three) “Beauty and the Beast” remixes, and then a scattering of other stories with varying degrees of fairy tale influence. It’s chaotic, seemingly unplanned. Or rather, it is planned on other levels—through theme and imagery.

But I was talking about the prose. The Bloody Chamber luxuriates in lush, Gothic language from the first paragraph-long sentence:

I remember how, that night, I lay awake in the wagon-lit in a tender, delicious ecstasy of excitement, my burning cheek pressed against the impeccable linen of the pillow and the pounding of my heart mimicking that of the great pistons ceaselessly thrusting the train that bore me through the night, away from Paris, away from girlhood, away from the white, enclosed quietude of my mother's apartment, into the unguessable country of marriage.

This is the kind of prose most MFA workshops would tear apart like wolves. It’s rich, comma-filled, and also hardly subtle. The whole story discards subtlety. The narrator’s husband—who is a version of the wife-killing Bluebeard as well as a nod to the Marquis de Sade—is constantly described as a beast. She sees the “dark, leonine shape of his head” and thinks about how he moves “softly as if all his shoes had soles of velvet, as if his footfall turned the carpet into snow.” This is a predator in the shape of a man. If you were still unsure, a few pages later he gives her “a choker of rubies…like an extraordinary precious slit throat” that prompts the narrator to think how “aristos who’d escaped the guillotine had an ironic fad of lying a red ribbon around their necks at just the point where the blade would have sliced it through, a red ribbon like the memory of a wound.” There’s some death in the works, just to be clear.

Here’s another Carter quote from the year after The Bloody Chamber’s publication: “The short story is not minimalist, it is rococo. I feel in absolute control. It is like writing chamber music rather than symphonies.”

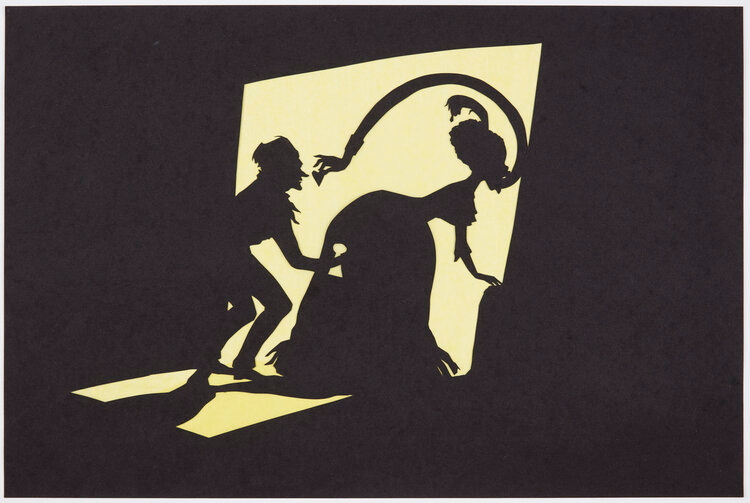

This rich and blunt imagery abounds in the book, and is appropriate for both Gothic fiction and fairy tales. In Kate Bernheimer’s classic essay “Fairy Tale Is Form, Form Is Fairy Tale,” she describes formal aspects of the fairy tale such as flat characters and notes “In a fairy tale, however, this flatness functions beautifully; it allows depth of response in the reader.” She brings up Kara Walker’s art as an example of how this works in visual media.

I think Bernheimer is quite right, and it makes me think about the way fairy tales, by their use of flatness and artifice, allow a depth of theme that more traditional narrative realism can’t achieve. Carter’s stories are bold in their explorations of violence, (hetero)sexuality, patriarchy, etc., in part because the the fairy tale flatness allows for it. We see something similar, I think, in “weird” writers like Franz Kafka. Stories like “A Country Doctor” don’t work because of their clever plot and character arcs. They ignore those in favor of psychological and philosophical depths.

Carter’s stories are free in their prose and also in their form. The Bloody Chamber stories break most of the structural rules of short stories. These are not stories of first page inciting incidents and so on. One of my favorites in the book is “The Werewolf,” a story that’s less than three pages in print. It begins:

It is a northern country; they have cold weather, they have cold hearts.

Cold; tempest; wild beasts in the forest. It is a hard life. Their houses are built of logs, dark and smoky within. There will be a crude icon of the virgin behind a guttering candle, the leg of a pig hung up to cure, a string of drying mushrooms. A bed, a stool, a table. Harsh, brief, poor lives.

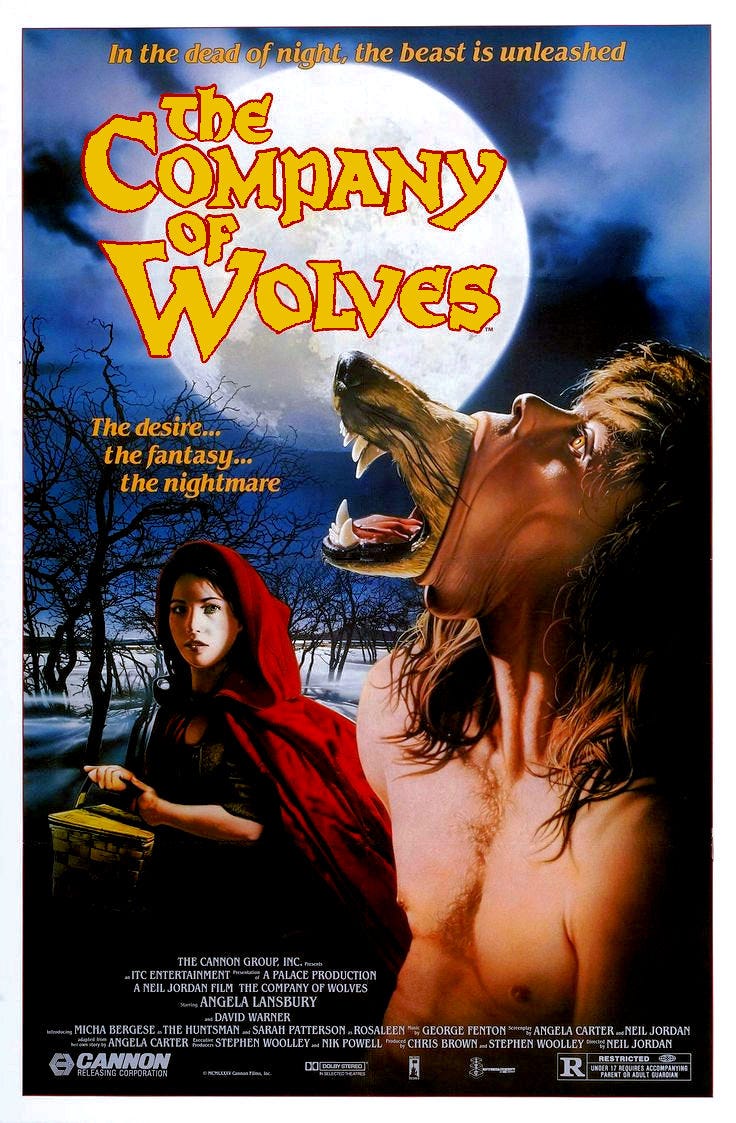

The story goes on like this for a few paragraphs and it isn’t until about the midway point that our hero, Little Red Riding Hood, appears. The next story, “The Company of Wolves” begins with five pages of mini-stories about various wolf-men and dark goings on before (another) Little Red Riding Hood appears. This one is quite spirited and later, when the wolf tries to eat her, laughs—“she knew she was nobody’s meat”—and leaps in bed with the wolf.

“The Company of Wolves” was the expanded and changed by Carter into a screenplay for a movie also called The Company of Wolves. It’s appropriately dark, weird, fabulist, and filled with wolves. Some of the film is a bit clunky but it does have perhaps the best bizarre werewolf transformation scene in all of cinema. (As the screenshot shows, it is pretty macabre. So fair warning.)

How does Carter pull all this off? Mostly, perhaps, her sheer mastery. Good writers can pull off anything and break every rule. But also, she dares to. In my edition of The Bloody Chamber, there is an introduction by the great Kelly Link. Link notes “The girls and women in The Bloody Chamber remake the rules of the stories they find themselves in with their boldness. And Angela Carter, too, was bold. I tried to learn that lesson from her.”

Carter is bold on the page. She’s willing to be lush, to break rules, to bend form. If a reader doesn’t like it, “So fucking what?” That’s a lesson every writer should endeavor to learn.

If you enjoy this newsletter, please consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.” Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

Carter is a true reader's writer, which is why literary scholars and nerds like me love her so much. She had a specialist's knowledge of fairy tales and folklore, which started when she translated Perrault's contes into English. She even once referred to The Bloody Chamber and her early writing as "lit crit."

I once wrote a 30-page paper that traced the cultural and literary allusions to Bluebeard in the title story, and honestly the paper could have been longer. She'd woven so many intertexual jewels into that one story alone. She wears the research so lightly, though, most readers won't know that La Bas is a shout-out to Gilles de Rais or that the Marquis is a reference to King Mark, and they don't really need to. Those rich layers of intertextuality soak into the story to give it the feeling of a palimpsest, like a ghost haunting the pages.

I wonder if this is part of the reason Carter's stories feel like they're spilling over at the edges and part of why her maximalism works so well. It helps to know all the notes of the old wine before you create the new stuff and watch the old bottles explode :).

"So fucking what" is all I need to know to want to read this author.