Why "Plot" Isn't a Four-Letter Word

On teaching yourself plotting and part one of an attempt to describe my "Principles of Plotting"

In personal news, I had a great time talking to Eva Langston about writing, editing, and my most recent novel Metallic Realms for The Long Road to Publishing podcast. Give it a listen here!

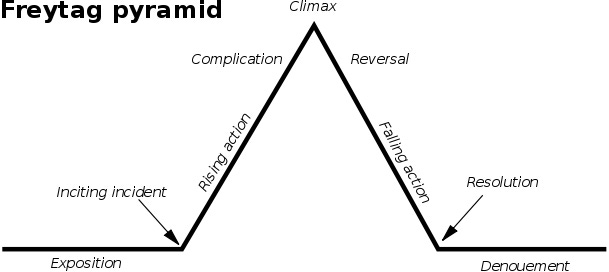

Before I could write my first novel, I had to teach myself plot. More or less from scratch. Despite several years of creative writing courses and many years of literature classes—in which I was introduced to many excellent authors and learned many useful things—I had been taught almost nothing about plotting and structure. Perhaps a vague notion that characters should “end in a different place than they start” and occasional references to Freytag’s Pyramid, but that’s about it.

Partly, this comes from the literary world’s aversion to plot, which is thought of as lowbrow or in opposition to more weighty matters like character and theme. Plot is sometimes envisioned as an artificial constraint on what should be an “organic story” (whatever that would mean). The attitude might be summed up in a frequently bandied-about quote from Grace Paley’s “A Conversation with My Father”1: “plot, the absolute line between two points which I’ve always despised, not for literary reasons, but because it takes all hope away. Everyone, real or invented, deserves the open destiny of life.” In the usual rhetorical escalation of social media, you will sometimes see literary writers (normally poets) claim “plot is fascist!” But it isn’t only literary fiction writers who spurn plot. Even Stephen King derided plot in his memoir On Writing, in similar terms: “I distrust plot […] because our lives are largely plotless” and “Plot is, I think, the good writer’s last resort and the dullard’s first choice.”

Much of this debate seems merely semantic. Some writers say they prefer “story” to “plot,” without really explaining the difference, or else conflate “plot” with “outlining.”2 I think plot is an element of narrative like any other. It is brilliant when done well and boring when done poorly. Writers have their own proclivities. Some prioritize plot over setting, or character over form, or dialogue over description. Anything can work. There are many excellent works of fiction that are largely “plotless,” and great ones that do not have “characters” in the traditional sense. I’ve enjoyed stories that are entirely in dialogue or that have no dialogue at all. The beauty of fiction is that there are countless ways to tell infinite stories. The rules do not exist.

Still, eschewing plot because you dislike formulaic stories is like renouncing character because you dislike stock figures and stereotypes. If a plot is too rigid and the hand of the author too overt, that’s bad writing. It isn’t the fault of plot per se.

The idea that plot is in opposition to innovative, experimental, or strange fiction is perhaps even backwards. A strong plot can be a sturdy foundation that allows you to build weirder and wilder structures, akin to how avant-garde painters use traditional subjects (like still lifes or portraits) as springboards to new styles. For The Body Scout, I found that using a hardboiled detective plot structure gave me more freedom to get stranger in my worldbuilding and other elements. But this was hardly a new trick. The list of writers who’ve borrowed hardboiled/noir plots for their own purposes—Thomas Pynchon, Kobo Abe, Cristina Rivera Garza, Roberto Bolaño, Paul Auster, Jonathan Lethem, Ottessa Moshfegh, etc.—is nearly endless.

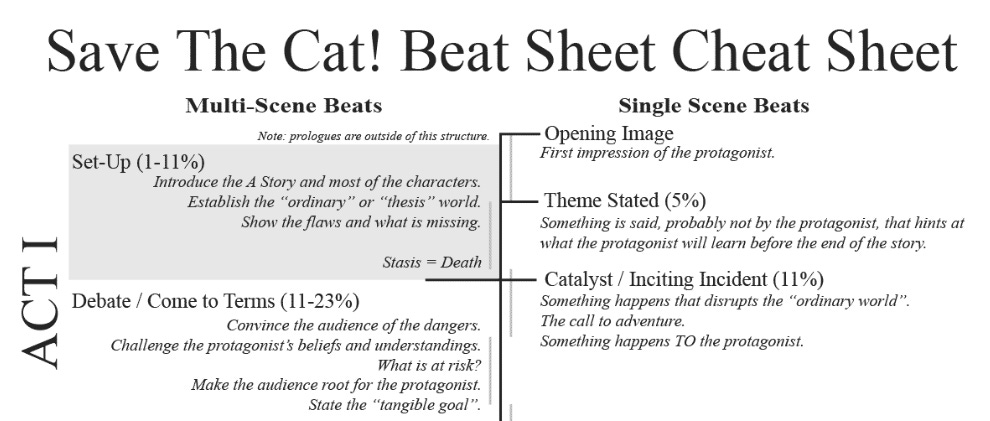

Many of my readers likely are nodding along, thinking, Yes of course plot is a useful tool. But for any readers who don’t like to think about plot or actively eschew it, I’m going to argue that plot is a skill worth honing. When I say I taught myself plot, this was mostly from studying great novels. But I also read up on narrative structures like Freytag’s Pyramid, the Hero’s Journey, Kishōtenketsu, and the Story Circle. I also found it useful to read screenwriting guides, such as Robert McKee’s Story, which approach writing in almost the opposite way of creative writing classes. The latter tend to focus on abstract—but also artistically freeing—ideas like “finding your voice” and “telling the story only you can tell.” By contrast, screenwriting guides seem bizarrely prescriptive. Here’s the start of a beat sheet based on Blake Snyder’s influential Save the Cat3 that lays out the exact percentages where plot beats should occur.

I roll my eyes at attempts to show a single story or monomyth, there are commonalities between all those structures and guides. Most offer a variation on the following: a norm is established (exposition) that is broken by a change (inciting incident) which leads to a question (or conflict) that is answered (resolved) at the end (climax), leaving the character(s) themselves changed (resolution). The norm that is changed might be the character’s world itself changing (“a stranger comes to town”) or the character being forced to enter a new world (“a man goes on a journey”). The ending might be the character’s entire world changing, the character’s situation changing, or simply their mindset changing.4 These ideas are all well and good, although I find them somewhat limiting. A lot of interesting fiction doesn’t really fit this model unless you really stretch the definitions. And anyway, you don’t need me to repeat Freytag’s Pyramid or the Three-Act Structure.

I try to synthesize all of the above. To balance the extreme prescriptivism of Hollywood guides or Hero’s Journey-type maps with the freeing yet vague advice of the literary world. For me, this takes the shape of what I’ll call story principles. Principles are not rules. They are not saying X must happen between beats Y and Z. And principles are flexible, applying to a wide variety of stories across styles and genres (though never, of course, covering everything). But principles also give you something more tangible to think about than “find your voice,” which may leave most writers shrugging their shoulders instead.

Last year, I said I was going to write a series of posts on “The Principles of Plotting.” I didn’t get to it then, but will write these this year. I’m not presenting these principles as a unique formula that I alone have uncovered in my literary alchemy lab. I’m not inventing anything new. I will cite and quote other critics and authors. But these are the principles that I like to keep in mind when I am writing. I’m not sure how many I’ll get to, but I’ll aim to cover at least Escalation, Variation, Oscillation, Intersection, and Redirection. The rest of this post will talk about Escalation.

Principles of Plotting Part 1: Escalation

In almost any type of story, we want a sense that things are escalating. That the story is growing and getting more intense/interesting/dramatic/what have you. That it is moving along whatever axis it is operating on. You can call this the dramatic stakes if you’d like. Or perhaps simply the force that makes the reader keep reading. A story without escalation tends to feel, well, flat or deflating. Imagine a sports narrative where the scrappy team wins the championship in act one and then spends the rest of the book playing meaningless exhibition matches. Or a superhero story that starts with defeating the big villain in a dramatic conflict then moves on to moderately difficult battles with henchmen and climaxes with the simple capture of a piddly street-level thug. Or a hardboiled story where the detective solves the big case at the midway point, then just goes home to tidy the apartment and have a relaxing weekend for the second half of the book.

These could all work in some sort of experimental metafiction story—in which case something else in the narrative would likely be escalating—but there is a reason that normally the team plays ever-more-important matches, the superhero fights ever-more-dangerous battles, and the detective discovers ever-more-important clues: we want stories to escalate. The battles and stakes get larger in each subsequent book of Lord of the Rings. Eleanor grows ever-more unstable/haunted in The Haunting of Hill House. The objects the titular police disappear in Yoko Ogawa’s The Memory Police grow increasingly extreme. Even in books we might not think of as plot-driven, there is usually something that escalates. It is just that what is escalating changes from genre to genre and style to style. In a language-driven story, it might be the mania of the narrative voice. In a surrealist story, it might be the absurdity of the situation. In a quiet domestic realism story, it may be the stresses on the protagonist that build until they are forced to make the decision that reveals their true character.

I imagine most writers are familiar with Freytag’s Pyramid. It’s often the only story model you’re ever shown in a writing class, although many others exist. In Freytag’s Pyramid, the section marked “rising action” is most akin to escalation, but much has been lost in translation. In Freytag’s model—which was based on a study of five-act plays—the “climax” is the turning point where the hero’s course is redirected rather than the point at which the central conflict comes to a head. E.g., in Romeo and Juliet the “climax” (in Freytag’s sense) is when Romeo kills Tybalt and thus ensures that his star-crossed romance can only end in tragedy. In a contemporary literature class, we would call the climax the scene near the end where Romeo and Juliet both kill themselves.

Outside of five-act Shakespearean tragedies, it is more useful to think of a story as escalating all the way to climax and then having a small amount of falling action or dénouement. In a Hollywood movie, this might be the last ten minutes of the film where the hero(es) take stock of the state of the world and/or return to their usual lives but changed. In a novel, this might be the last chapter or epilogue. In a short story, this is often a short final paragraph, single sentence, or even just a final clause.

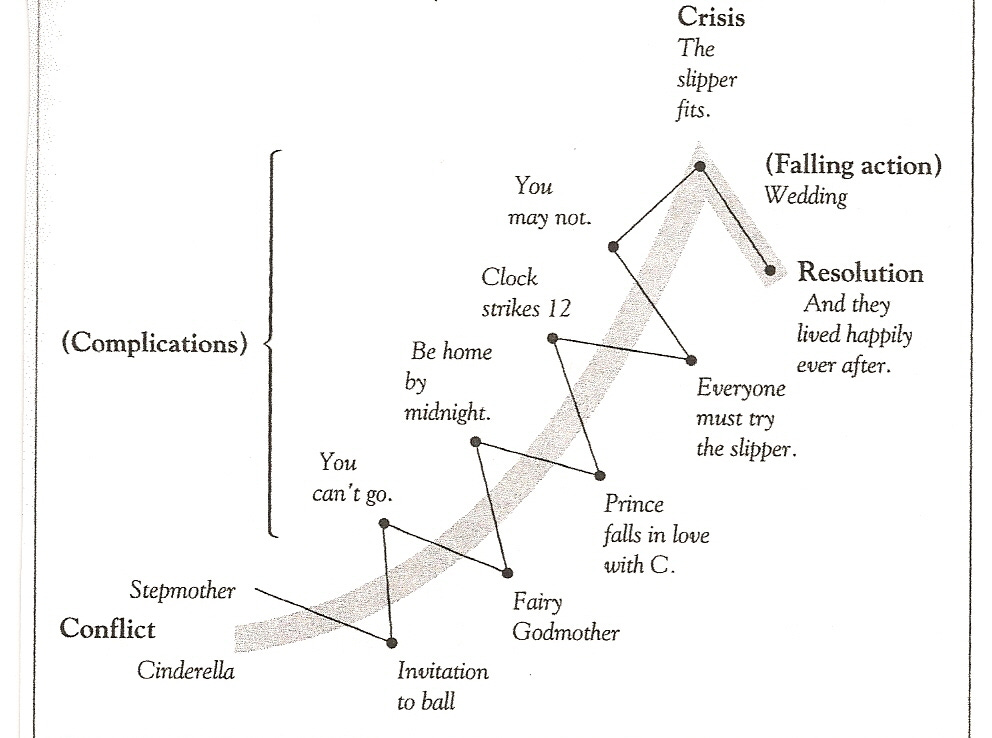

A story model I find more flexible is Janet Burroway’s upside-down checkmark, here mapped with Cinderella:

Again, what is escalating will differ from story to story and genre to genre. It may be a character’s despair or their hope, a failing marriage or a budding romance, the character’s descent into madness or their looming epiphany. It can be multiple things at once. As always, the specifics depend on the specific work and the the genre, style, and themes you are engaging.

I do think escalation, while not universal, is common in most stories from Hollywood blockbusters to experimental short fiction. And it can certainly be misapplied. The demand for escalation is why TV/film sequels always have more villains and crazier plotlines, often to the point of being overstuffed or underbaked. No principle should be followed mindlessly.

Everything I’m saying about escalation is pretty basic. But the basics are often forgotten. When I read student work that feels inert, it’s often because the story lacks escalation. The characters meander about with not much going on and then a “sudden outburst of plot” occurs at the very end to wrap the story up. Or if a plot is present, that plot is not structured so that it escalates. The beats feel out of order where the opening is more dramatic than the ending or the stakes seem to lower as the tale goes on. Normally, this is not done with intention. The writer is not trying to subvert expectations, but simply didn’t think much about the order of the story. They wrote the scenes as they came to them and figured that was that.

That’s fine to do in a first draft. But in revision, the author should be thinking about the sequence of moments, scenes, and events and the overall shape they are making. Revision often means rearranging. Escalation is a principle to keep in mind not just for the ending of the story—not just to make sure your climax wows—but for the whole duration. When you’re looking at your story or novel, think about whether the chapters and scenes are in the right order so that the story has a sense of escalation from start to finish. Are your scenes increasing in intensity and interest? Would the narrative be more intriguing or dramatic if the order of chapters or scenes were changed? I my experience at least, many narrative problems can be solved without major rewriting by simply reordering.

Of course, there are always caveats and there is a big one with escalation. You don’t want your escalation to be too clean, too rigid, too expected. If your character is climbing up a straight slope at a steady incline, that’s predictable. Who wants to read predictable? A trick of plotting is providing a sense of both escalation and unpredictability. The couple in a romantic comedy can’t inevitably march from good date to great date to blissful marriage. The action hero can’t beat ever-stronger enemies with no setbacks. A character’s climactic choice only reveals their character if it seems possible they might choose another way.

Two principles that usefully complicate escalation are what I’ll call variation and oscillation. I’ll talk about those in my next “Principles of Plotting” post.

My new novel Metallic Realms is out in stores! Reviews have called the book “brilliant” (Esquire), “riveting” (Publishers Weekly), “hilariously clever” (Elle), “a total blast” (Chicago Tribune), “unrelentingly smart and inventive” (Locus), and “just plain wonderful” (Booklist). My previous books are the science fiction noir novel The Body Scout and the genre-bending story collection Upright Beasts. If you enjoy this newsletter, perhaps you’ll enjoy one or more of those books too.

This quote is not actually Paley stating her personal aesthetic conviction, but rather a character in a work of fiction. The subtext of the story is that the narrator is refusing to accept the “closed destiny” of her father’s impending death.

This seems to be how King defines it, as he insists he doesn’t plot because he doesn’t outline ahead of writing.

The title refers to the idea that you should make your hero (especially if an anti-hero) do an act of kindness very early on, such as saving a cat from being run over by a car, that will make the audience root for them.

A character getting what they wanted at the beginning of the story, only to find out it isn’t what they wanted at all at the end of the story, is a classic version of the mindset change.

In my one published novel and my current WIP, I've been a "pantser": someone who writes/plots by the seat of their pants. I take no perverse pride in that, nor do I recommend it: it's labor-intensive and, in my case, entails throwing a lot of early writing out (though I never REALLY throw anything away: you never know when it may come in handy).

One advantage to pantsing, however, is that developments in my own plot sometimes sneak up and surprise me. I see connections between incidents that I hadn't planned. Characters do unexpected things.

One tool I've stumbled on only recently is to plot chapter by chapter. I brainstorm a list of possible incidents from beginning to end. Then I write, referring to my outline, highlighting the parts of it I use and striking through the parts I don't.

I'm still teaching myself how to do this, and I'm grateful for that. This is a fine, practical post, Lincoln.

Such a helpful post. When I was writing the first draft of the novel I'm working on now, the lack of plotting was part of what made me start over. I had a vague three-act structure in mind but nothing scary happened in the first/third of what was supposed to be a horror novel, and I realized that was... not good.

I came across a 7-point structure and plot-mapping ideas in Save the Cat! Writes a Novel, and it helped way more than I anticipated. I don't follow it religiously, but it's useful to have a reference that prompts me to think, "Oh, is it time for a plot turn?" More often than not, so far, the answer is yes. Or, I'll move too quickly to the next Thing, and then realize there needs to be escalation or misdirection in between. I'm a convert now.