Structure and Its Discontents

Some thoughts on kishōtenketsu, Freytag's Pyramid, and taking what you want from structure

This week there was a minor internet debate about “conflict” in stories that I won’t bother linking to, but which brought up a pet peeve. Namely, Americans (yes normally white Americans) claiming non-Western stories are free of “conflict” and “causality” (!) because they use kishōtenketsu. Typically, Miyazaki is the example of conflict-free and non-causal storytelling. This stance is meant to be progressive I think, but is obviously a bit othering and orientalist. It also seems wrong all around.

Anyone familiar with Japanese narratives know they frequently center conflicts of all sorts and “causality” is hardly a story concept limited to the West. At the same time, plenty of Western narratives are surrealist, non-linear, fragmentary, and so forth. Indeed, people daily complain that American literary fiction is just “plotless” stories where “nothing happens.” It should also be obvious that there isn’t one type of Western or one type of Japanese narrative (and that there are many non-Western countries other than Japan with their own artistic traditions). There is an infinite variety of stories in any culture, and culture always cross-pollinates. Kurosawa’s films were major influences on American Westerns and blockbusters like Star Wars, and Miyazaki was heavily influenced by Western films and novels. Etc.

Anyway, Miyazaki’s films are quite popular in America so framing them as having alien structures that American minds can’t grasp is a little strange. (Even more amusing, Miyazaki has said he found the traditional kishōtenketsu structure so constraining that he abandoned it decades ago in favor of less structured storytelling. )

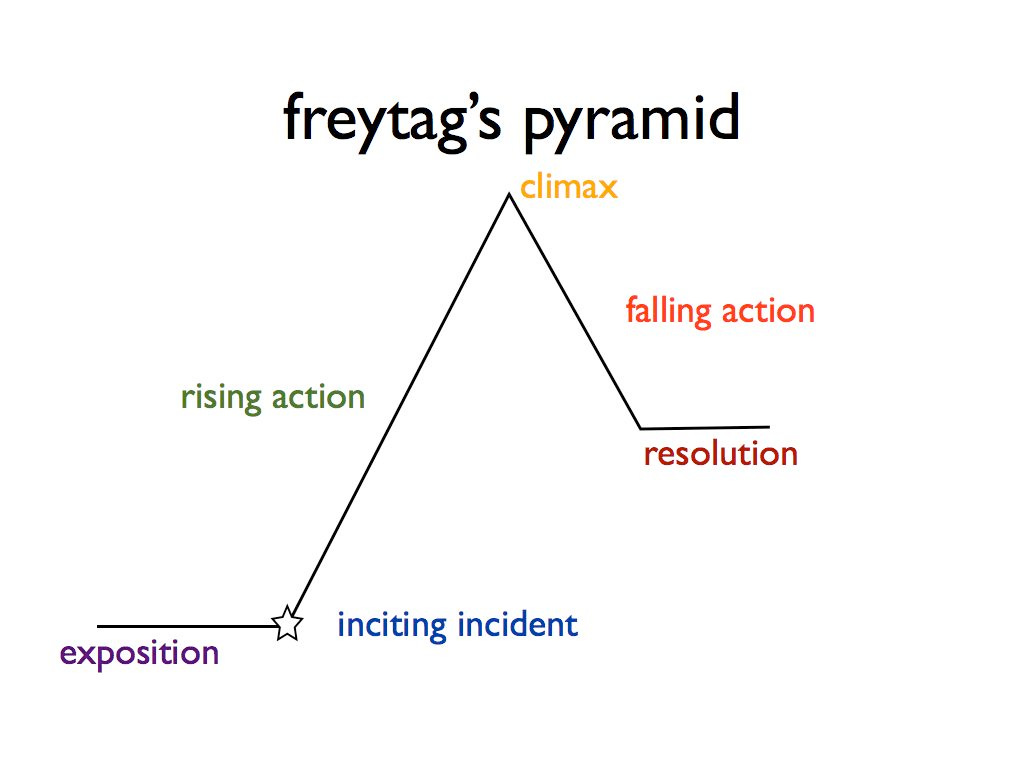

But let’s talk about structure. The first thing I think is important to remember about story structures is that they’re typically abstracted to such a degree that they can apply to nearly anything. Some years ago the news was filled with articles about how “every story in the world has one of these six basic plots.” Researchers analyzed books for use of “happy” and “sad” words which they translated to a story having either rising or falling action. They discovered that all stories have some variation of rising and falling. The six plots are variations of rising and falling to three steps—rise, fall, rise/fall, fall/rise, rise/fall/rise, fall/rise/fall—and all other narratives could be said to be versions of these six.

Well… duh? Tautologically all narratives viewed through a lens of falling and rising will have some variation of falling and rising in some combination. That’s all that could possibly be discovered within the parameters! (It only stops at 6 plots because by the artificial cutoff. If they went to four steps we could have rise/fall/rise/fall narratives and so forth.)

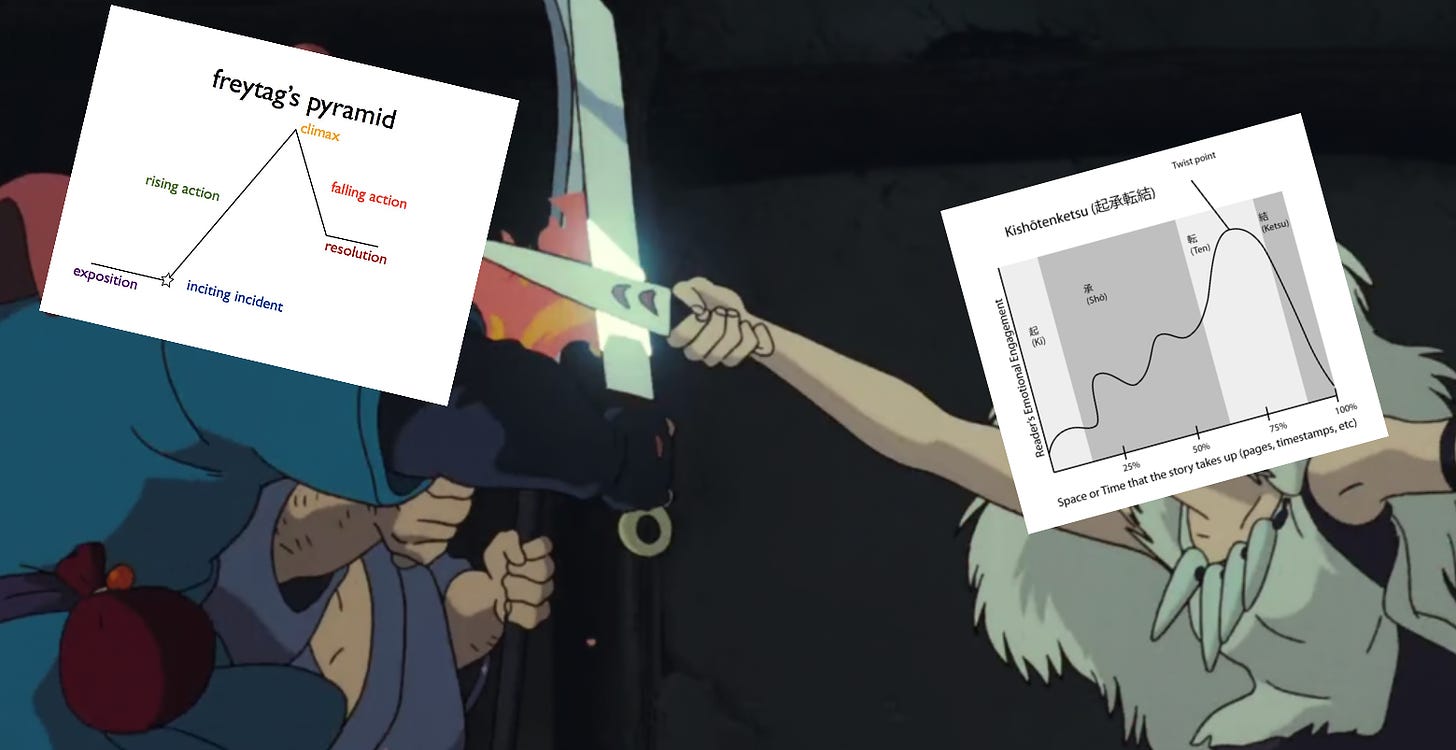

In this way, structures are more useful as ways to think about existing stories or to generate new stories than they are evidence of fundamental differences between themselves. Squint at my header image, and these two structures look almost the same, no?

So, what are these structures?

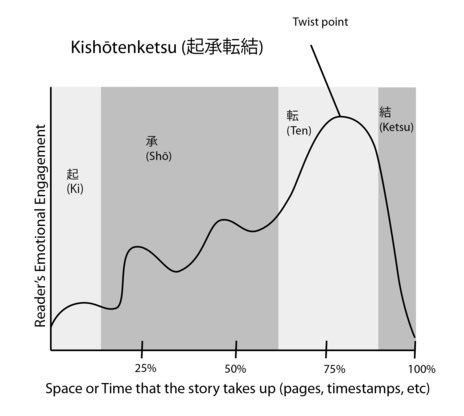

Kishōtenketsu is a four-part structure that originated in Chinese poetry, but in Japan today is perhaps akin to the three-act Hollywood structure or Freytag’s Pyramid in the sense of being a general structure that can be applied to many narratives in different mediums. Here’s a video of some Japanese manga artists breaking it down. The steps can be translated as 1) introduction 2) development 3) twist or turn 4) conclusion.

When this structure is brought up in America, it’s normally to highlight that it doesn’t necessitate “conflict.” For example, here’s an article from Mythic Scribes that gets frequently linked. That the structure doesn’t have conflict built into the four beats is true. At the same time, even the classic Western Freytag’s Pyramid structure doesn’t have conflict built into the steps. (As Wikipedia notes, Freytag himself “argued for tension created through contrasting emotions, but didn't actively argue for conflict.”)

I think it’s true that Hollywood blockbuster movies have an overfocus on conflict in a fairly rigid structure. If you’re used to only watching big budget action films, then movies from other cultures may surprise you. But Hollywood blockbuster movies aren’t all Hollywood movies, much less all Western movies, much less all narratives in all mediums.

Anyway, these abstract structures can and are mutually applied. A Japanese critic may discuss Hollywood movies through kishōtenketsu just as Western critics will analyze Japanese films through the three-act structure or hero’s journey. As an example, I’ll use Mythic Scribes’s own example of Kiki’s Delivery Service, the most commonly referenced film among the “Miyazaki doesn’t have conflict” crowd. Here is how the article summarizes the structure of Kiki’s Delivery Service as evidence it is free of conflict:

Ki Kiki doesn’t quite feel at home in the big city which is very different from her own little village

Shō Kiki is beginning to doubt whether a witch can be accepted in such a big city.

Ten Tombo gets into trouble and Kiki saves the day.

Ketsu Everything works out well in the end.

This fits the kishōtenketsu quite well. But I don’t need to alter a word to fit it into the textbook “character vs. society” conflict cited in one hundred million internet articles. Kiki is an outsider in conflict with her society, her problems escalate, she completes a heroic act, and she is now accepted by the society. The same story beats are used in Disney films. Now, that doesn’t mean Miyazaki’s films are identical to Disney films. Only that the same abstracted structures can be applied to both. We can do this in reverse. Ki A young elephant named Dumbo is mocked for his large ears. Shō Dumbo is increasingly bullied and shunned at the circus Ten Dumbo learns he can use his ears to fly and wows everyone. Ketsu Everything works out well in the end.

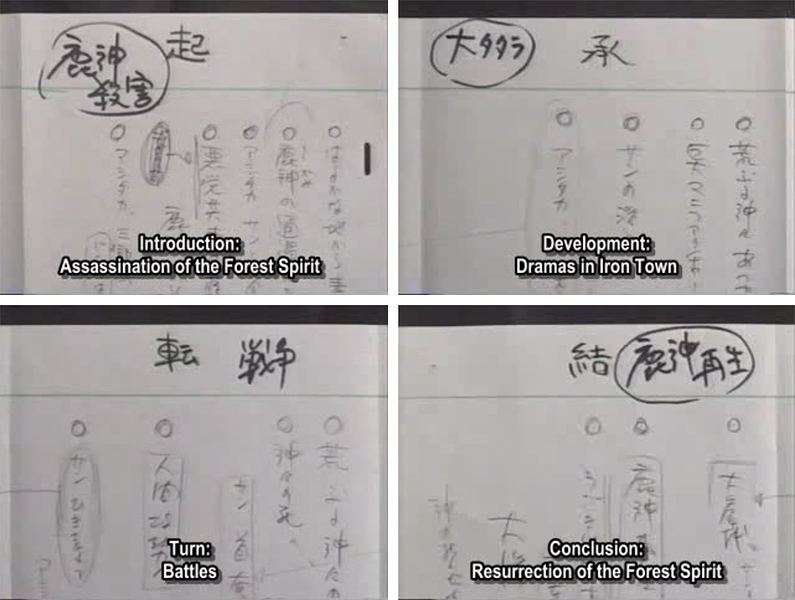

Here’s another example of outlining a Miyazaki film with kishōtenketsu, in this case the film is my personal favorite Princess Mononoke. The film stills are from How Princess Mononoke Was Born (stills taken from here). Surely it’s not hard to compare the ten aka “turn” third act of “battles” with a Hollywood movie climax. Princess Mononoke has a clear inciting incident (Ashitaka’s village is attacked and he’s infected) and has rising action and all the usual beats in Freytag’s Pyramid. You could also easily map the Hero’s Journey (Ashitaka goes on a quest, meets mentors, has an abyss moment, is transformed, etc.) onto this or any of these films too.

This doesn’t mean the stories are all the same by any means. I don’t think Disney would have made Spirited Away anymore than Miyazaki would have made Frozen. It is just that abstracted structures can fit anything. What story doesn’t have an introduction and a conclusion? What story doesn’t have some kind of climax or twist? What story can’t be broken into three or four acts? We could indeed name some—Invisible Cities is always my go-to example—but most narratives can fit rather comfortably into either structure.

For writers, I think is useful to think about different structures to remind yourself that there isn’t just one way to think about these things. Hollywood screenplay guides can at times be ludicrously prescriptive, but other conceptual structures like kishōtenketsu exist around the world. The real question is what structure is generative for you in any given project? If you want to decenter conflict and thinking in terms of “development and twist” instead of “rising action and climax” helps you do that, that’s great. If a given project is better thought of as two acts, or three, or four, five, or more, go for it. And if you’re feeling your work is getting stale relying on one structure, ditch it and try a new framework.

Why not get even weirder with it? Jane Alison’s Meander, Spiral, and Explode asks writers to think about a variety of structures such as spirals, explosions, and waves. Or, like Martin Solares does in this Lit Hub essay, why not draw your own weird shape?

Structure is only constricting if we let it be. I think it is quite helpful to learn about different story models from around the world—and even more useful to read widely and deeply from across cultures and time periods. Take what interests you and is productive for your work. Cobble together your own structure idea from various parts. If it’s not working, ditch it. Try something new. Read some more. Find something new to try. That’s all we can ever do.

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.”

Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

Some stories just don’t fit into traditional western structures. I’m writing a novel now in what I’m calling a Collage structure, though I’m not sure it fits the official definition. It certainly feels like a collage though.

What is the structure of Beloved? What is the structure of The Rabbit Hutch? That’s what I’m trying to define.

Thank you for your post. I always appreciate talk of different structures.

Great essay! Along somewhat similar lines, but dealing with non-fiction, this article by Julia Rosen for The Open Notebook compiles a series of different approaches to visualizing structure:

https://www.theopennotebook.com/2015/10/20/narrative-x-rays-stories-structural-skeletons/