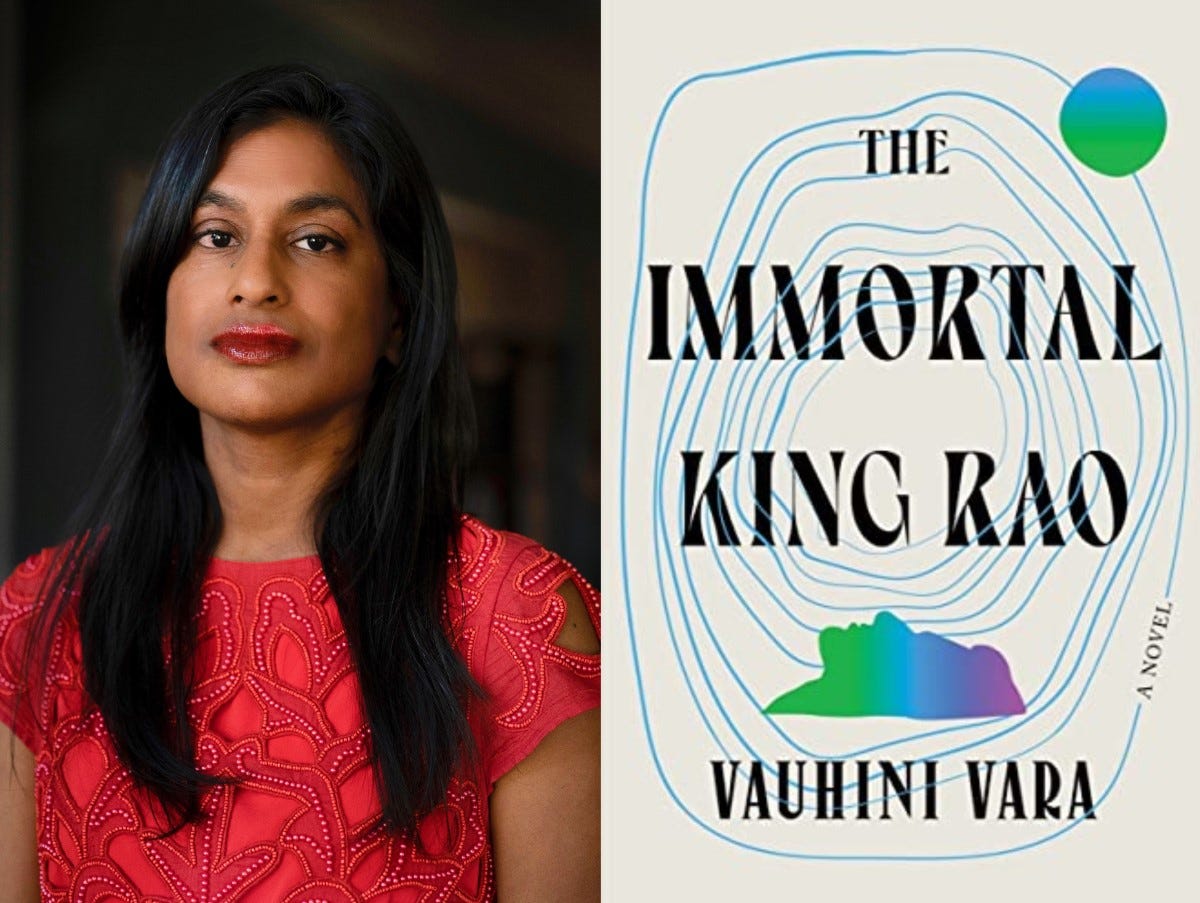

Processing: How Vauhini Vara Wrote The Immortal King Rao

The author on genre blending, the differences between journalism and fiction, and publishing her debut novel

Every now and then I like to interview authors about their writing processes for this newsletter, and I’m thrilled to have been able to talk Vauhini Vara, whose novel The Immortal King Rao is easily one of the best books I’ve read this year.

The Immortal King Rao is a true genre-bender mixing family drama, historical fiction, tech satire, and near-future science fiction into a unique and engrossing novel. The story spans time from 1950s India to 1970s America and a future where the world’s citizens have become “Shareholders” in an algorithm-driven corporate dystopia. There’s so much I loved in this novel. The tech satire is razor sharp—Vara has long worked as a tech journalist—and Vara’s prose is equal parts moving, humorous, and thought-provoking.

I talked to Vara about blending genres, how journalism informs her fiction, and the process of completing and selling The Immortal King Rao.

Your novel blends different genres like historical fiction and science fiction. How did you decide on mingling genres in this way and were there any books (or other art works) that inspired the form?

So, the initial idea for the novel came from my dad. In January 2009, we were traveling together, and he was teasing me about writing only short stories and not a novel, and I was like, “Okay, dad, give me an idea for a novel, then”—and he did. He said I should write about a Dalit family on a coconut grove in Andhra Pradesh, in India—based on his own family. At the time, I’d just taken a leave of absence from a tech reporting job at the Wall Street Journal, where I’d been writing mostly about Oracle (and Larry Ellison) and Facebook (and Mark Zuckerberg). I found these men and their companies and the socioeconomic systems in which they were operating really fascinating. So I had this idea to start with a child growing up on a coconut grove like my dad’s, in the 1950s, but then have my character, King Rao, move to the US and start a tech company in the 1970s. But then I had a writing problem—a craft problem—which was that these kinds of experiences, both growing up as a Dalit boy on a coconut grove in India and starting a tech company in the 1970s as a man, seemed so distant to me; I felt like I lacked the authority to write about them from the perspective of the main character.

At the time, my husband and I were watching the Battlestar Galactica reboot from the mid-2000s, where there’s this technology that allows some characters to access one another’s consciousnesses, and I was like, Ah, if I could just have my narrator use a tool like that, the narrator could tell these stories—about the coconut grove in the 50s, Silicon Valley in the 70s—without having to exactly embody King Rao himself. That narrator eventually turned into Athena, King’s daughter, who can access his consciousness using her mind. All of this is to say, in the case of this novel, all the choices felt really organic to the needs of the book — and my needs, as its writer. I wasn’t aware at the time of books with a similar form or structure. That’s one reason I’m especially interested in your writing about the speculative epic. It seems like all these writers settled on this kind of form around the same time, more or less independently.

How did you keep track of the various timelines and worldbuilding elements? There is a lot going on in the novel, but it all reads very smoothly and I never felt lost. Did you use any program like Scrivener or your own systems to keep timelines, characters, and such straight?

I was really groping around in the dark for so much of this process—all of it, maybe. At first, I was using Scrivener, but I could never really figure out how to properly use all of its features, so at some point I moved the whole manuscript to Google Docs and wrote the rest of it there; I used the super-basic outlining tool in Google Docs to keep track of what I was putting in the book, in what order. (At the top of each chapter, I’d summarize what was in it, and then that would automatically show up in the outline.)

For a long time, the structure of the book was a total mess; early readers—friends, my husband, my agent—would tell me that the transitions from each chapter from the next felt whiplashy and confusing. What I ended up doing, after each draft, was outlining the book so I could understand exactly what was problematic about it. Then I’d try something else and have more people read it. And at some point, people stopped saying it wasn’t working, and that’s when I thought, OK, we’re good here.

You mentioned that your father gave you the first nugget of the novel idea in 2009. If you’re willing to share, can you talk about the overall process of writing, revising, and selling the novel?

I was in graduate school when I started the novel; that trip with my dad, in 2009, happened just after my first semester. I began writing it pretty soon after that—over the following spring and summer; that fall, I told a friend that I thought I would finish and sell it within a year and a half. In the summer of 2010, I traveled to India for a month to do research on the India-related portions of the novel; I interviewed relatives, along with experts on coconuts, on caste, on Indian history.

And then I returned home and had to go back to work; I’d taken a two-year leave of absence from working as a reporter at the Wall Street Journal, and my time was up. Once I went back to work, it got a lot harder to sustain work on the novel. I’d write pretty much every weekend, and some mornings and evenings, but progress was really slow. In 2014, I got pregnant and decided I needed to sell the novel right away, before the baby arrived, so I sent it to the agent I’d gotten in graduate school. She was thoroughly unimpressed and basically fired me. Soon thereafter, I met a new agent, Susan Golomb, who also saw issues with the manuscript but also saw a lot of promise in it. I signed with her, and she gave me some notes; she said she thought I could probably respond to them in a matter of months.

Then I had the baby, and that slowed things down further. Several more years passed. Still, I kept writing whenever I could. I started freelancing, which gave me flexibility to take some time off from work, once I’d earned enough during a given period. Residencies, at MacDowell (once) and Yaddo (twice), played a really important role; so did a grant from the Canada Council for the Arts—Canada’s version of the National Endowment for the Arts in the U.S.—which bought me a couple of months to finish the novel toward the end. Finally, in early 2020, we sent the novel out, and in March, we sold it to Alane Mason, an editor at Norton. That was followed, of course, by another couple of rounds of edits. Alane was happy with it before I was. I kept revising and revising and revising, and finally, Alane intervened—she pried it out of my fingers and published it.

You cover technology as a journalist and editor. How did your writing process on the novel differ (if at all) from your work as a journalist?

Truthfully, the biggest difference is that I’ve been paid for working as a journalist and editor—I write or edit something, it’s published, and I get compensated soon thereafter—while my work on this novel, over 13 years, went uncompensated for a long time. That meant that I always had to prioritize the work as a journalist and editor; creative writing came next, when I could squeeze it in.

Craft-wise, the problem to be solved feels the same, for me, with journalism and fiction. You have some material in hand, and your job is to turn that material—plus some yet-nonexistent material—into a piece of writing. It feels daunting, in both cases. With journalism, the job is to go out and find the truths that need to be told in order for the piece to be fully realized—they’re out there, but you just don’t know how to find them at first. It requires an outward-looking approach and real doggedness: sending cold emails; making phone calls; going down rabbit holes in random public databases. With fiction, on the other hand, the job is to imagine your way to the truth; similarly, it’s in there somewhere (though in this case, it’s internal, rather than external), but you just don’t know how to find it at first. Doggedness isn’t quite the right approach, here; you can’t force it, the way you sort of can with other things. You’re basically daydreaming your way to the solution.

Could you imagine returning to the world of King Rao for a future novel? And what are you working on next?

This had never occurred to me, but over the past couple of weeks, as people have finished the book, a lot of readers have asked this question—or have even suggested that they found the ending to be strategically open-ended, to leave room for a sequel. Still, though, I can’t imagine returning to the world of this novel. The arc of the characters’ stories feels complete to me; I don’t have that curiosity about what happens next that I think would be required if I wanted to revisit this world in another novel.

What’s next, instead, is a collection of stories, This is Salvaged, which Norton will publish next year. I’m editing those stories now. And I’m also starting work on a collection of experimental essays—it’ll include this essay called “Ghosts,” which the Believer published last year, among others—having to do with technology.

Thank you so much for talking with me with me! Any bits of wisdom you can share for aspiring debut novelists out there?

I’ll share the same wisdom that I received, over and over, early in my own writing career, which is that the only thing that distinguishes writers from non-writers is the writing—which is to say, if this is something you want to do, then go ahead and do it and keep doing it. Don’t stop.

Previous Counter Craft writing process interviews include Matt Bell, Alexander Chee, Chandler Klang Smith, and Calvin Kasulke.

As always, If you like this newsletter, please consider subscribing or checking out my recently released science fiction novel The Body Scout, which The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent” and Boing Boing declared “a modern cyberpunk masterpiece.”

I juuuuuust bought this book-what perfect timing!!

Lincoln, what other books have you read that explore “future worlds” like this? I’m very into this genre right now, but it seems like everything in the future fantasy space is more sci-fi/space-centric/dystopian/apocalyptic which I’m not as into... any recs?

Great interview! It’s amazing to hear how Vaunini kept at the same novel for years and years. Very encouraging!