How Chandler Klang Smith Writes with Robots

The author on collaborating with AI writing programs and getting around writer's block

A few weeks ago, I wrote a newsletter about what I saw as the great (and perhaps terrifying) potential of AI visual art programs and the comparatively weak and uninteresting reality of AI writing programs. AI visual art programs like DALL-E are already producing usable art and can imitate unique styles. On the other hand, AI writing programs don’t seem to be able to produce much beyond some accidental surrealist sentences. Nothing interesting at the macro level of plot, character, or scene. Maybe AI programs will replace novelists one day, but that seems far off. They aren’t even useful to collaborate with.

Or so I thought.

My friend and author Chandler Klang Smith commented on my Facebook post saying that while she agreed that AI writing programs weren’t able to replace novelists, she in fact was already collaborating with one for her next novel. I found her description particularly intriguing: “it's like a robot has a dream about your work in progress and you get to decide if anything from that dream reflects what you're trying to do.” I was eager to hear more and Smith agreed to answer some questions for this newsletter.

Chandler Klang Smith is a great writer and teacher whose debut novel, The Sky Is Yours, is a wild genre-bending work that combines postmodern playfulness with epic fantasy adventure. It was named a best book of the year by The Wall Street Journal, NPR, Lit Hub, and elsewhere. Check out it, if you haven’t already.

Can you tell me a little about how you got started using SudoWrite. What made you think about using an AI program could be useful?

Almost exactly a year ago—April 2021—the writer Stephen Marche, who’s a Facebook friend of mind, published an article in The New Yorker entitled “The Computers Are Getting Better at Writing.” It opened with a dramatic hook: a surprisingly convincing paragraph that purported to be a section from Kafka’s The Metamorphosis but that was actually generated without human intervention by SudoWrite. I reached out to Stephen over Facebook Messenger and he helped connect me with the appropriate person at SudoWrite to become a beta tester. We also had a thought-provoking back-and-forth about the issues raised by this technology: although Stephen is a bit more pessimistic than I am about its implications, we agreed that the ultimate question for us as artists is whether a tool like this can help make writing better, since there’s certainly no shortage of bad or even competent but lackluster writing out there.

My theory, that I expressed to him at the time, is that removing the obstacle of the blank page is potentially revolutionary—it gives the writer material to shape and react to, and/or to curate. Kind of like photography. Diane Arbus didn't make her subjects' faces, but she spotted what was interesting about them and pointed them out to others through her art. So I didn’t (and still don’t) share the fear that the SudoWrite will lead to writing without an identity or personality.

But I probably should rewind a bit further. The reason I read that article with such interest was that I was already fascinated with AI-generated text, and the reason I was fascinated with AI-generated text was almost completely due to this bizarre Facebook account called Bots of New York. I don’t know if you’ve seen it, but the posts on there parody the person-on-the-street photography and interview project “Humans of New York” via often nonsensical images and monologues from these stream-of-consciousness bots. I haven’t independently verified this, but the human admin of BoNY claims it’s all AI-generated.

For a long period during the pandemic, Bots of New York was the only fiction—if we can even call it “fiction”—that I got any enjoyment out of reading. It was hilarious, full of language-level swerves and reversals, with the trippy logic of an exquisite corpse or an experimental Adult Swim show. I was also dazzled that anything resembling literature could hold my attention enough to stop my doom-scrolling even for a couple of paragraphs, or inspire fellow doom-scrollers not only to read and comment but buy merch. I wanted to steal some of that fire for myself.

I find all of this very fascinating and a lot of your thinking mirrors mine. I remember when Gary Kasparov lost to Deep Blue and the predictions that advanced computers would destroy chess as a game or sport. However, it quickly became clear that even if computers can beat humans easily, well, few people have any interest in watching two computers play chess against each other. It’s just not interesting for most of us. So people still play chess and the big shift has been computers assisting humans in training. This seems like the artistic version of the chess question. Can computers assist us in making art?

I absolutely think they can, and that it will be a bigger and bigger part of the process for many authors.

There are tons of parallels for this in the visual art world, but one that springs to mind for me is my favorite artist Judith Schaechter. She works in the medium of stained glass—she (usually) hand draws images, hand etches the surface of the glass with those images, layers different colored panes on top of one another to create specific hues and ghostly overlays, then solders copper foil to hold the pieces together in the composition. It's hard to imagine a less digital process than this! But when I heard her speak at a recent art show, I was fascinated to learn that she uses Photoshop to store, manipulate, and combine the images that she ultimately uses in her art. I would never have suspected that from the finished product. So I think even writers who are much less interested in work that retains the weirdness of the AI "voice" will find ways to employ this or related tools in their process.

Right now, SudoWrite and the other programs I’ve heard about mostly generate prose. But I could also imagine future AIs that help identify patterns that already exist in what someone has written, or that help authors switch tenses or POV, or that organize/make searchable materials related to a project (I don’t use Scrivener but a lot of writers I know do, and I could imagine a system like this being even more helpful with a level of AI assistance). Most contemporary writers already use spelling and grammar check without even thinking about it, and we have templates for resumes and other common documents on our computers, so I don’t think it’s far out to imagine people would accept this even if they don’t share my enthusiasm for, say, BoNY.

So how has your experience been? When you commented on Facebook, you said that the program didn’t rise to the level of collaborating with a human and explained it with this really interesting phrase: “it's like a robot has a dream about your work in progress and you get to decide if anything from that dream reflects what you're trying to do.” Could you expand on that?

Honestly, that’s the best description I can offer of what SudoWrite feels like. I don’t use it every time I sit down to work on my book, and as others have pointed out, it’s really unhelpful at macro stuff like plot and structure (except by giving the writer one idea at a time, as you’ll see in my example below). But when I’m stuck, I do find that using the “wormhole” or “describe” functions can unlock ideas that seem like they were already buried somewhere already in the text. It truly does remind me of the—all too rare—occasions when I’ve solved a writing problem with a dream… except the AI dreams on command.

A couple of times, SudoWrite has even given me a short chunk of prose or dialogue that I was able to integrate into my manuscript with relatively minor edits, which feels like literal sorcery. In a field where we’re taught to be so watchful about plagiarism it feels odd to slot in words that weren’t originally your own, but in a way these words are mine, since they never would have been generated without my original inputs. And then I think about Burroughs’ cut-ups or Jonathan Lethem’s essay “The Ecstasy of Influence” and I’m bowled over by the potential for writers to use similar techniques without the risk of infringement.

It’s worth mentioning that the novel I’m working on right now is highly experimental and meta (think, Paprika meets I’m Thinking of Ending Things) so I’ve given myself a lot of freedom to use dream logic and swap genres at will – if I’d had this tech when I was writing The Sky Is Yours, which is comparatively plot and world-building heavy, it might not have been quite as directly useful.

This makes me want to try SudoWrite myself. I have to confess that your Facebook comment made realize I’d missed a major area of potential AI application in my newsletter. Like you, I’ve found that AI can sometimes generate fun/weird/surreal little bursts of text. In this way, it reminds me of cut-up exercises or “weird things my kid said” tweets. And also like you, my attempts at generating longer AI texts have produced nothing interesting at more macro levels of plot, structure, character arc, etc.

But I really hadn’t thought about AI as a writing block workaround. This might be because I’m not the kind of writer who has problems with the blank page (this is not a brag, I have many other problems with many other steps of the process!).

Before using SudoWrite, did you use analog blank page work arounds such as the Burroughs’ cut-ups you mentioned or erasure poems or Oulipo games?

I’ve totally written line-by-line parodies/homages to existing texts. In The Sky Is Yours, for example, I include a screenplay for a recruiting ad by the Metropolitan Fire Department (which fights fires caused by the dragons ravaging the city). In order to come up with it, I basically transcribed an existing US Army commercial and then went through beat by beat, substituting in my own language and context, obviously, but keeping most of the structure and rhetoric. I also have poem parodies in Sky that I created the same way. Some of my motivation here was certainly to give the book a postmodern, allusive texture, but it was also easier than coming up with these whole cloth sans models. I do not share your superpower of fearlessly confronting the blank page :-)

When I was first seriously writing as a teenager, I did try cut-ups (I have a painful memory of reading what was probably a pretty incomprehensible one at an open mic poetry event), but as an adult with publication in mind for my work I’ve always steered clear of anything with an attendant risk of plagiarism or copyright concerns. Even getting epigraphs okayed is a hassle in traditional publishing.

I followed the case of QR Markham and Assassin of Secrets back in 2011 with a lot of interest and non-zero sympathy, though – the idea that someone could write a propulsive spy novel, of all things, that consisted mostly of stolen text suggests to me that what we lump together as “writing ability” might actually have a couple of separable constituent parts, only one of which is an author’s talent for/interest in composing their own sentences.

Could you share any examples, either of SudoWrite text you found interesting or of how you integrating some into a passage?

The book I’m writing is so weird I’m not sure this will make enough sense for you to include, but I can give it a shot.

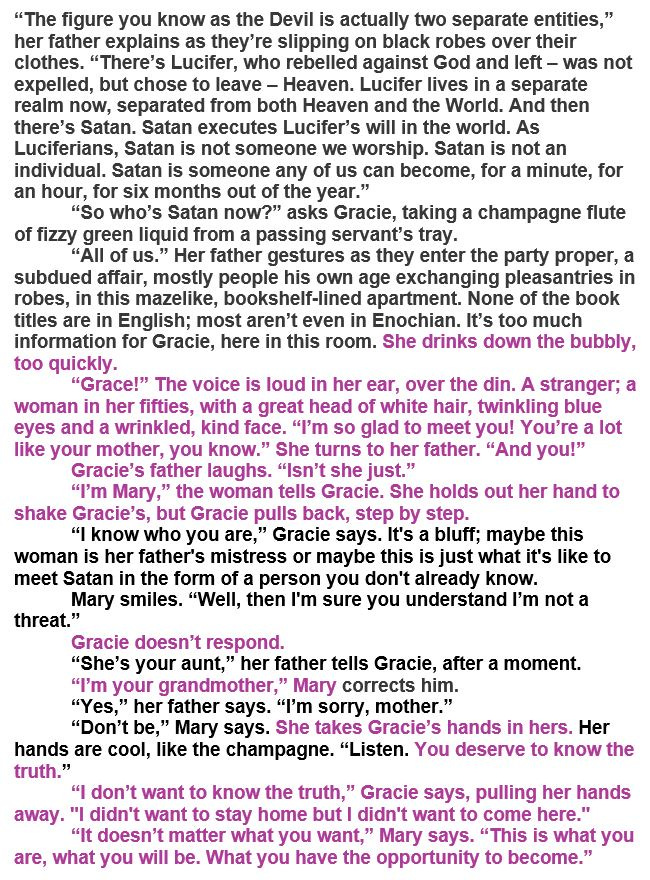

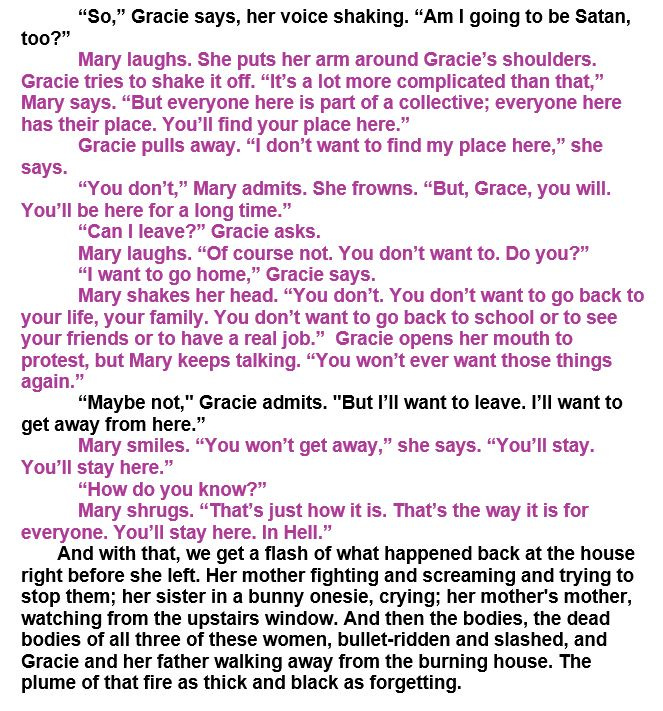

This scene was the part of the book where I probably kept the most prose directly from SudoWrite. It’s a nested story (in a novel that’s rife with them)—a Rosemary’s Baby type film that the characters are watching, about a girl who leaves home with her semi-estranged father to join a Luciferian cult. I knew I wanted this scene to be creepy as hell, but I couldn’t figure out what needed to happen to achieve that. SudoWrite had an answer: Mary.

The parts in black here are my text. The first chunk, ending with “here in this room,” is what I initially gave SudoWrite. In response, it generated the parts in purple. I went in, edited, and added the text in between and after those purple parts, which appears here in black. This is one of my favorite passages in the book, and the first time I’ve ever written something I genuinely find unsettling… possibly because I didn’t write it alone.

I love this, and thank you so much for sharing! I agree this scene is quite creepy and I’m impressed with how much of the SudoWrite text is used (as well as your skill in making it work with your own text.) One thing that strikes me here is that it might be fair to say you are using the flaws of AI text as a strength. By that I mean that AI text still seems unable to perfectly mimic human writing or speech (e.g. incomplete lines like ““Isn’t she just.”), but because of that it might be ideal to use for passages that are uncanny or surreal. If AI is in the “uncanny valley,” why not embrace that?

Well-put: I totally agree. I’d add that, although this is totally not my writing jam, I could see the SudoWrite working well for children’s literature too, especially work at the more zany, nonsense-y end of that spectrum. As you’ve noted before, writing by actual children often has a super free associative quality that it can be difficult for adults to duplicate so SudoWrite might be a way to tap back into that.

And do you have any final thoughts about collaboration with AI?

I can certainly imagine ways in which future AI collaboration could be employed to limit authors’ creativity – an AI coming in to “correct” a manuscript, for example – but at this moment in time, the technology that exists, exists for us to use as a tool. So I for one want to explore what it can do.

Thank you so much for chatting with me about this. And I can’t wait to read the new novel when it’s out!

Haha, thanks. Here’s hoping I manage to finish it before the inevitable robot uprising.

As always, If you like this newsletter, please consider subscribing or checking out my recently released science fiction novel The Body Scout, which The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent” and Boing Boing declared “a modern cyberpunk masterpiece.”