Let Me Tell You About "Show Don't Tell"

This "rule" is neither a CIA psyop nor does it mean what some critics think

The central trust of this newsletter is exploring counterintuitive writing advice and poking holes in the alleged “rules” of writing. I like to look at alternate ways of structuring stories than “conflict,” defend boring sentences, and argue characters don’t actually have to change. Art is infinite. There truly are no rules. But sometimes a “rule” is so misunderstood and dismissed that defending it—or at least explaining it—actually seems like the contrary position. One example is the much-maligned “show don’t tell.”

“Show don’t tell” is a vague rule of thumb that many writing teachers jot in the margins of workshop submissions. It’s a reminder that readers respond more to what they can “see” in scene than what they’re just “told” in exposition. Most professors don’t treat it as any kind of iron-clad “rule,” although I’m sure some professors somewhere are overzealous with the phrase. But for many people on the internet, not only is “show don’t tell” over-prescribed advice it is literal CIA brainwashing developed in laboratory in Langley to destroy left wing politics and control the minds of every writer and reader in America.

This meme has gone around Twitter for a long time, and today Current Affairs published an article by Annie Levin about how “the rise of creative writing programs and ‘show don’t tell’ philosophy drained fiction of its political bite.” The article repeats a lot of the myths about the CIA and writing programs I’ve written about before. The tl;dr response is that yes during the Cold War both the USSR and America funded artists in a battle for cultural supremacy, sometimes secretly. However, in the US it was more a “throw it against the wall and see what sticks” approach than a magical “psy-op” campaign that had figured out what kind of aesthetics could mind control America. The CIA promoted literary realists but also abstract expressionist painters and writers like James Baldwin and Latin American magical realists we’d hardly call “de-political.”

In any event, it feels quite strange to see people claim the CIA “de-politicized” literature in the 60s or 70s. You see no politics in Toni Morrison, Thomas Pynchon, the New Wave science fiction writers, etc.? Most of what people complain about as de-political writing seems to be a reductive idea of post-Cold War literary realism that wasn’t the dominant school of literary fiction in the time when the CIA allegedly pulled the strings. That’s not even getting into all the other genres of fiction people read.

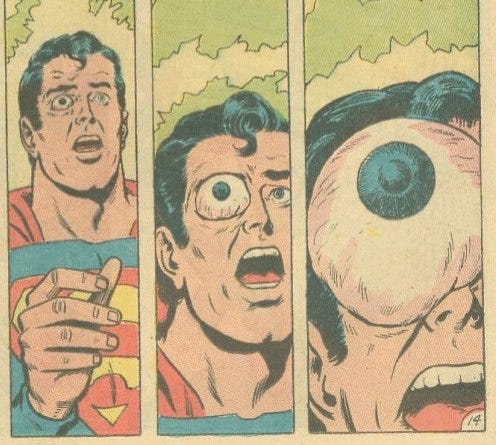

But CIA aside, what made my eyes bulge in the Current Affairs article was the explanation of “show don’t tell”:

You may, for instance, have been told that writing should “show and not tell.” In some ways, this advice is sound. To show (sensations, experiences, and memories) and not tell (doctrines, dogmas, and philosophies) in narrative fiction is a good idea. While people love to enthuse over what interests them, what readers need to know to understand what is happening usually needs to take precedence over a writer’s passions. […] The problem with “show don’t tell” is that applied to actual literature it becomes over-simplistic. Literature historically is full of dogmas, doctrines, and philosophies.

This is just not what “show don’t tell” means. It is not about writing memories over philosophies or having characters have only sensations and not beliefs. It’s certainly not about avoiding a “writer’s passions”! I’ve never once heard anyone argue this in any of the creative writing courses, craft lectures, or craft books I’ve read. If someone has made the claim, I think they also misunderstand both the idea of “show don’t tell” and how fiction works in general.

But lots of people seem confused about the term. I’ve even heard it means avoiding dialogue, since that’s characters “telling” things. So what does “show don’t tell” mean?

At least as I’ve ever heard it, “show don’t tell” is a rule of thumb for how information is best delivered to the reader. It’s not about what type of information to convey. Both memories and philosophies can be “told” or “shown.” The gist is that readers are typically more engaged with “scene”—characters moving, talking, feeling—rather than exposition. We tend to connect to characters and feel things more strongly when information is filtered through people. So “it was a hot day” is less evocative than “Eloise was sweating through her shirt.” A related idea is that specificity is more visual and thus more interesting. “Asha walked into the shop to buy a cake” is less interesting than “Asha walked into the little blue pastry shop on the corner hoping they still had a slice of their special black forest cake with the ring of raspberries on top.” And visual or other sensory details are more evocative than plain information. So “Raj got embarrassed” is less evocative than “Raj’s face turned bright red” or even “Raj blushed” to stay concise.

That’s… really it. That’s what “show don’t tell” means.

The origin of the idea is typically attributed to Chekhov, who apocryphally said “Don't tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass.” (In reality: In descriptions of Nature one must seize on small details, grouping them so that when the reader closes his eyes he gets a picture. For instance, you’ll have a moonlit night if you write that on the mill dam a piece of glass from a broken bottle glittered like a bright little star, and that the black shadow of a dog or a wolf rolled past like a ball.) Moonlight glinting on broken glass is an evocative visual image that activates the reader’s imagination in a way that “the moon was shining” doesn’t.

Does “show don’t tell” mean characters shouldn’t have beliefs or ideologies? Of course not. If you want to apply it, it means that it is better to have scenes of characters arguing their beliefs in dialogue with each other rather than have a narrator simply state their opinions.

Again this is pretty basic stuff, not complex mind-control.

Of course, it wouldn’t be a Counter Craft post if I didn’t also contradict or complicate the advice. So here’s a few additional ideas.

First, it’s certainly true that great writers can break all the “rules.” Plenty of brilliant passages, stories, and chapters have been written in “telling” style with minimal “showing.” Filtering information through characters in scenes is effective. But so is having a compelling narrative voice or writing style.

Secondly, even if you are looking to “show” it’s important to remember that virtually all fiction involves both “showing” and “telling.” If some over-zealous writing teacher claims you should never tell, ignore them. You need both exposition and scene, at least in most works. The way to apply this rule is to show the most important information for your themes, story, and characters. Show us the pivotal scenes, the dramatic peaks, and the crucial plot twists. Tell us the information we might need to know, but isn’t as dramatic or thematically important. Part of this is a question of emphasis, signaling to the reader what is important, but another part is time management. Put simply: telling is typically quicker than showing. It takes less words to sum up a conversation or scene than to summarizing it. So understanding when to tell and show is a crucial aspect of controlling the pacing of any story.

Thirdly, I would argue that there are showing ways to tell and telling ways to show. By that I mean that one can write exposition that is full of evocative details and visual metaphors and conversely you can write scenes that are completely dull and forgettable. “I’m very angry in the mornings,” Jack said as he made an angry face might be technically “showing” but… it’s not terribly interesting or visual. In the mornings, Jack was as grumpy as grizzly bear crawling out of its cave on the first day of spring is—well bad writing—but it’s a “telling” sentence that includes a visual metaphor the reader can see.

What is true for conveying emotions and sensations is also true of conveying ideas. There is a reason that philosophers from Plato to today have “shown” us what they wanted to “tell” with visual metaphors, characters, and even fictional scenes. Plato could have simply told us his ideas about building an ideal society, but he knew—despite his grumbling about the poets—that writing scenes of characters acting and speaking and using visual metaphors was more effective.

What’s true of Plato is true of most philosophers and political theorist across the ideological spectrum. Even the densest philosophical treatises and political manifestos are often filled with “showing” moments, because the authors know that we respond more to what we see than what we’re merely told.

As always, If you like this newsletter, please consider subscribing or checking out my recently released science fiction novel The Body Scout, which The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent” and Boing Boing declared “a modern cyberpunk masterpiece.”

Like the toll of a bell, this article resonated deeply.

Wrestling with this exact issue at this exact time; how to portray philosophical positions of partisans just before the Civil War. Great information and insight.