Every few months, someone on Twitter hears that the CIA helped fund the Iowa MFA program in the 1960s and soon the discourse has decided that all creative writing advice stretching back to Aristotle is a “CIA psyop.” This is only a slight exaggeration. I don’t want to call individual Tweeters out, but it’s easy to find people claiming “show don’t tell” and “write what you know” are CIA propaganda or that “MFA-style” fiction (whatever that means) is a form of social control.

(“Show don’t tell” is advice passed down from Anton Chekhov, a pre-Russian Revolution author who died several decades before the CIA was founded. So unless there is a time-travelling CIA agent seeding creative writing advice throughout space time....)

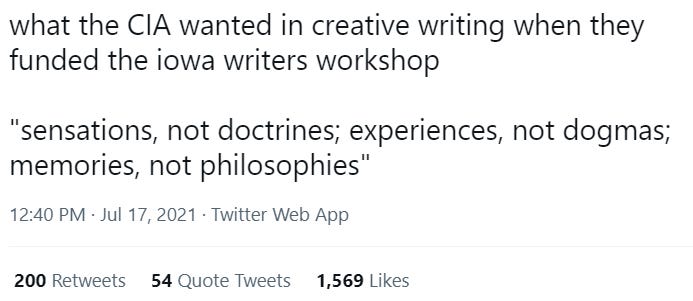

Twitter is, of course, not known for its adherence to context, nuance, or history. In the most recent viral thread on the subject, a third-hand summary of former Iowa MFA director Paul Engle’s philosophy of literature—“sensations, not doctrines; experiences, not dogmas; memories, not philosophies”—is being quoted in a way that makes it read like an actual CIA mission statement.

While the CIA has an obviously vile and bloody history, and it’s amusing to imagine some CIA spooks huddled around trying to come up with a style of literary short fiction to control the population, the actual history of CIA and government arts influence is a pretty interesting if more complex one.

The claims about the CIA’s influence in creative writing programs is mostly sourced from Eric Bennett, an Iowa MFA grad. His work has been critiqued, for example for conflating Engle getting funding for an international artist program after he had left the Iowa Writer’s Workshop with the IWW itself. And anyway Bennett himself does not argue what the above tweet does much less the extrapolated claims. Bennett found that Engle, after he stopped being the MFA director, “received $10,000 to travel in Asia and Europe to recruit young writers—left-leaning intellectuals—to send to the United States on fellowship” as a way to counter a similar USSR effort to woo artists. Interesting! And weird. But hardly proof that the entire field of creative writing in a CIA psyop.

Still, it’s certainly true that the CIA via various channels funded or promoted many different artists and arts organizations during the Cold War. For example, the CIA famously (if secretly) boosted abstract expressionist painters like Pollock and Rothko to counter Soviet Realism. I highly recommend Joel Whitney’s Finks for a look at how CIA money ended up helping found The Paris Review and other CIA literary entanglements. The CIA also allegedly promoted left wing magical realist authors in their attempts to influence Latin America as well as writers like James Baldwin. And needless to say the Soviet Union puts tons of money into funding artists. During the Cold War, everything was a field of battle including the culture.

The history is fascinating, but of course the Twitter conclusions are often far removed from the actual history. The fact that the CIA was promoting abstract expressionism and magical realism as well as (allegedly) preaching non-abstract non-magical literary fiction and poetry probably doesn’t indicate the CIA figured out that that a certain aesthetic style was a form of social control… nor does it mean that, decades later, if you are influenced by James Baldwin or Marquez you’ve been duped by the government. Much of the CIA efforts promoted American art as superior to Soviet art and ergo the US as superior to the USSR. This doesn’t mean the CIA’s influence was good much less that the CIA itself is good (most definitely not). But there’s no evidence that vague MFA jargon like “write what you know” or “show don’t tell” are MK-Ultra tactics.

It’s also perhaps interesting that during the period in which the CIA is alleged to have been pulling the strings of literary fiction across the country, the “postmodern” style of fiction that Bennett said was forbidden at Iowa was perhaps the most popular around. In the 60s and 70s, you were more likely to find a non-realist, idea-driven story by Robert Coover or Donald Barthelme in the New Yorker than the Lorrie Moore/Raymond Carver minimalist realism school that is today so associated with MFAs. (Carver’s breakout book and Moore’s debut were in the 1980s.) Barthelme, Coover, and many other postmodernists taught at MFA programs too so postmodernism has hardly been excluded from the MFA world. American literature, like any literature, goes through different waves with competing styles, principles, and theories constantly clashing. If there is a good lesson here, it’s that craft advice isn’t a set of timeless scientific principles but different ideas that reflect different histories, theories, and styles.

Anyway, like many literary scuffles the whole thing feels oddly quaint in 2021. It’s hard to imagine the government caring about little poems published in small magazines when the most dominant entertainment is militaristic (and near fascistic) superhero films with global reaches and billions in revenue. If I was a time-traveling CIA art operative, I’d be implanting myself at Disney not Iowa…

"Anyway, like many literary scuffles the whole thing feels oddly quaint in 2021. It’s hard to imagine the government caring about little poems published in small magazines when the most dominant entertainment is militaristic (and near fascistic) superhero films with global reaches and billions in revenue. If I was a time-traveling CIA art operative, I’d be implanting myself at Disney not Iowa…"

What's even more quaint is to believe that the Cold War ever ended. A list of prominent Hollywood films which were produced with "assistance" from the Pentagon can be found here, including blockbusters from 2022:

https://www.academia.edu/4460251

What's more, Call of Duty, an extremely popular video game franchise, is also produced with assistance from the Department of Defense:

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/oct/22/call-of-duty-gaming-role-military-entertainment-complex

The Chekhov quote regarding "show, don't tell" also has a totally different meaning from the view widely propagated in creative writing courses:

'"Don't tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass." What Chekhov actually said, in a letter to his brother, was "In descriptions of Nature one must seize on small details, grouping them so that when the reader closes his eyes he gets a picture. For instance, you’ll have a moonlit night if you write that on the mill dam a piece of glass from a broken bottle glittered like a bright little star, and that the black shadow of a dog or a wolf rolled past like a ball."' (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Show,_don%27t_tell) Interestingly, this quote comes from a book of Chekhov's untranslated work—first published in English in 1954.

Chekhov here is advocating for specificity of detail, not to avoid ideological commentary in writing. In modern contexts, "show, don't tell" means that we are supposed to focus on the senses and avoid authorial commentary. It *can* mean specificity of detail ("He was sad" versus "His tears run down his beard, like winter's drops From eaves of reeds") but it *definitely* means that we should avoid explaining things to the reader—like, for instance, that characters in novels which take place in the modern imperial core are miserable because they are bourgeois parasites, not necessarily just because of their own individual atomized problems.

Assuming this comment isn't deleted, I recommend that curious readers have a look at this article (https://www.currentaffairs.org/2022/04/how-creative-writing-programs-de-politicized-fiction). It states, notably, that the Iowa Writers Workshop—the model for all other workshops, which are themselves often founded by IWW graduates—was funded by CIA front organizations. Years before Engle's CIA-funded trips abroad—I wonder why they decided to give him so much money in the first place?—his work at the IWW was also funded by the Rockefeller Foundation (https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-iowa-flattened-literature/?cid2=gen_login_refresh&cid=gen_sign_in), whose ideological goals are indistinguishable from those of the CIA, and which—like the CIA—is also closely linked to Nazism. Interestingly, the IWW was far from the only organization affected by the Cultural Cold War. The Paris Review—which has published some of your work—was founded by a CIA agent.

But what was the effect on American literature? Let's see...

"When I was first studying literature in college, I started putting a dividing line between literary novels written before and after World War II. It seemed like the books from the before times were good at doing lots of things. They could world build and philosophize. They could be love story, adventure novel, and satire all in one. Books written after the war, however, could only do one thing at a time. Mostly that one thing was soul-searching or introspection. Serious postwar fiction, whether it was what I was being fed in school or read in the pages of The New Yorker, was about sad white people with relationship problems."

The CIA—an organization staffed by Nazis rescued from Europe at the end of the Second World War, and their ideological descendants—fully admits to involving itself heavily in virtually every aspect of society. The quaintest thing of all is the fact that liberals know this and don't care.