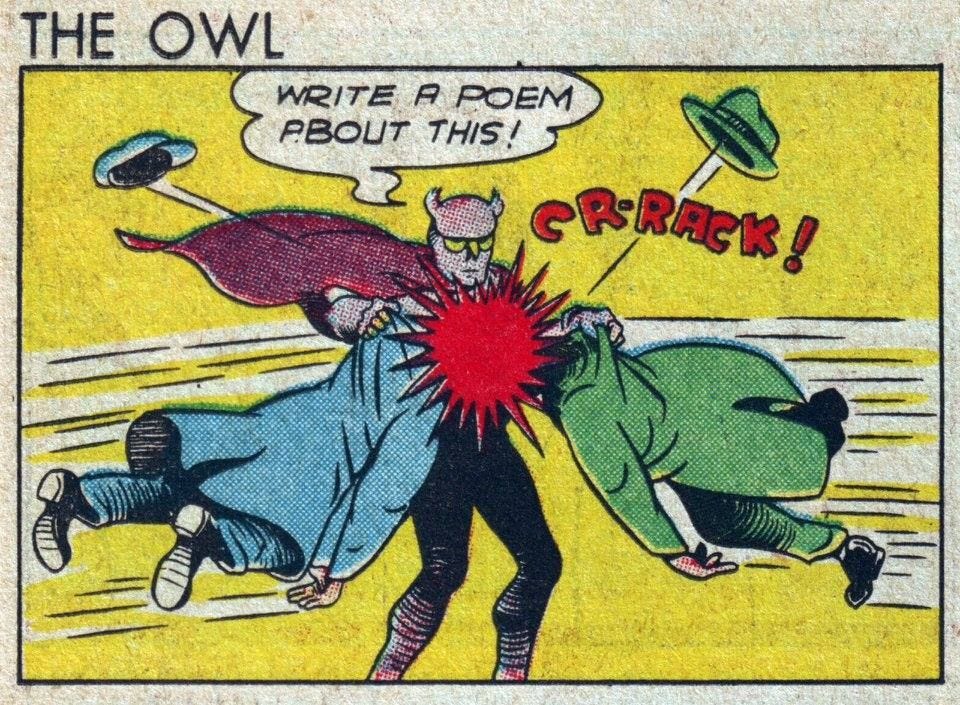

Conflict Is Only One Way to Think About Stories

Some conflicting feelings on conflicts in literature

If you’ve been reading literary Twitter this week, you’ve almost certainly seen a lot of, uh, conflict over the question of conflicts in literature. Are all stories driven by conflict? Or is that claim both false and perhaps even a problematic way to think about stories? A whole lot of very smart writers have weighed in falling on one side or the other …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Counter Craft to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.