Is Your Worldbuilding Up To Code?

On the infinite ways to build cities, realms, worlds, and galaxies

In personal news, I’m thrilled that Metallic Realms is still getting coverage more than a month after publication. Electric Literature included Metallic Realms in a piece on comedic science fiction: “This one will leave you cringing, asking your friends if you’re the Annoying One, and laughing out loud.” And here on Substack, Danny Sullivan wrote a very kind and thoughtful review of the novel with an accurate (IMHO) title of “The Charles Kinbote of Millennial Losers” and called Metallic Realms “a testament to the power of having fun, and to the deeper meanings that playing around can bring to light.”

If your interest is piqued, consider checking out the novel. Metallic Realms also, coincidentally, dramatizes some of the arguments about “worldbuilding” (among other things) that I’m talking about today.

A couple weeks ago, Lillian Wang Selonick wrote a smart article on worldbuilding in The Republic of Letters that brought up an old essay of mine called “Against Worldbuilding”:

The rising use (and overuse) of the term led to a brief literary dustup in 2017 prompted by Lincoln Michel’s provocative essay Against Worldbuilding. Michel argues that worldbuilding is only useful in some very specific science fiction/fantasy secondary world contexts, and that an over-reliance on top-down, nuts-and-bolts fictional universe engineering is tedious and unnecessary in the vast majority of cases. Instead, he argues convincingly for something he calls world-conjuring, which is the light-handed use of evocative details that allows the reader’s imagination to fill in the logic of a fictional world. The essay triggered a slew of responses from worldbuilding’s defenders.

I really enjoyed Selonick’s piece, and who doesn’t love to cause a literary dust-up? I’ve talked about the topic of “worldbuilding” in different ways in Counter Craft. But reading Selonick’s essay made me think I might as well revisit, restate, and rethink my arguments from “Against Worldbuilding” in this space.

Against (Limiting Ourselves to One Type of) Worldbuilding

Despite the “Against Worldbuilding” title, I’m in no way opposed to the dominant mode of worldbuilding. You probably can’t be a SFF nerd if you don’t enjoy getting lost in lore and exploring, discussing, and arguing over the details of imaginary worlds. I’ve gone down my share of wikipedia holes about Arrakis, Middle-Earth, and Westeros. Many of my favorite novels, such as Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed, wouldn’t work without worldbuilding. In the hands of an author like Le Guin, worldbuilding goes hand-in-hand with the exploration of ideas in a way that enriches both.

I do think there are dangers for writers in focusing on worldbuilding. Many young writers can fall into the trap of spending forever fleshing out the logic of their world, the lore of their factions, the rules of the magic or technology, so on and so forth… and then forget to actually write the damn book. Even professional writers can fall into the trap of expanding their worldbuilding until the whole story implodes. (*Cough* George R. R. Martin. *Cough*) But those aren’t my main concerns.

I worry that worldbuilding has gone from a term for the various ways we can conjure a fictional setting in prose to an argument that there is one way that imagined worlds must be built. The way some people talk about worldbuilding is like saying that buildings require “four walls at right angles” and then declaring gazebos, pyramids, igloos, pavilions, etc. to be failed structures.

What I love about fiction is its infinite possibilities. Stories can be constructed in any form, take any shape, center any subject, and be told in endless styles. Even the same story can be constructed in endless ways, in much the same way that painters can render the same subject in countless styles. Isn’t that what makes art great?

But the hardening of one way of “worldbuilding” into the Official Rules of Good Worldbuilding shrinks art. It gives us fewer possibilities. And that’s always something to push against.

What People Mean by “Good Worldbuilding”

One definition of worldbuilding is merely whatever the author does to construct a fictional setting on the page, whether detailed or sketched, logical or intentionally illogical, consistent or chaotic. By that definition, all stories have worldbuilding. In practice, many have a narrower conception of worldbuilding—or else they would not spend so much time discussing “failed” or “lazy” or “bad” worldbuilding.

What people typically mean by the word these days is what I’ll call consistent, explicated, rules-based worldbuilding or CERB. Just kidding. I will not inflict a geek acronym on you. Instead, let’s call this “hard worldbuilding” since it is entangled with the concept of “hard magic” and to a degree “hard science fiction.” Hard worldbuilding insists upon consistent worlds in which the speculative elements are explained and everything operates in a logical, rules-based fashion. In science fiction, this means giving “scientific” explanations for every technology, alien race, and idea. But something similar should occur in stories of wizards, dragons, or other illogical things. See, for example, bestselling fantasy author Brandon Sanderson’s influential “laws” of magic that explain why even magic should be rules-based and explicated. Sure, magic isn’t science. Yet it should be treated as science so that a reader will e.g. know exactly what spells a given character can cast with what knowledge or ingredients they have. (Sanderson is expressing a preference not entirely dismissing other modes of the magical. But for many young writers, this has become the “right way” to do magic.) In one way, this kind of SFF worldbuilding is similar to historical fiction. The author is providing the reader with both the facts and the explanations to understand how this world really works.

Since this type of worldbuilding is taken as dogma, I don’t need to spend much time defending it. Again, I enjoy many books in this vein and I get the appeal. By making the rules of the world consistent, explicated, and rules-based, the reader better understands the stakes throughout the story. Hard worldbuilding helps create large and immersive worlds that readers can get lost in but also that authors can luxuriate in. It’s likely the ideal method of worldbuilding for really long works, like epic fantasy trilogies or space opera series.

I do think that the expectation for explanations for every worldbuilding element can cause problems. Most shorter works simply can’t explain everything without overwhelming the story. This is true for a short story, obviously, but even a single novel or film. Audiences watching Star Wars: A New Hope didn’t need explanations for “the clone wars” and “the Kessel run” much less a faux-science explanation for the Force or the history of every random background character. They were just little seeds of worldbuilding to give texture to the world. (Well, until Lucas and Disney realized they could milk every throwaway line and side character in an ever-expanding franchise.)

There’s also point at which the obsession with the logic of a fictional world and the “canon” can blind you to what the artists are trying to say. Under the pretense of rigor, fans can ignore the harder and more interesting questions that good art raises. See for example Adam Kotsko talking about the attitude some Star Trek superfans developed:

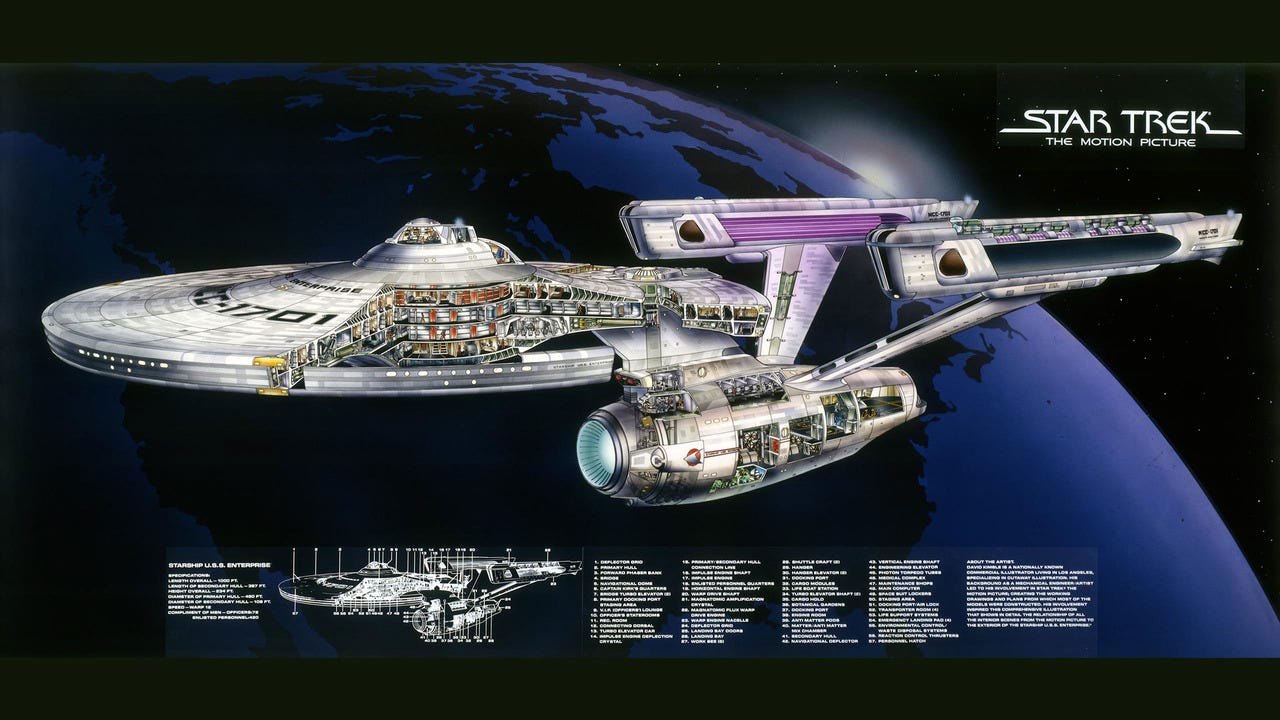

I found in my discussion with fans that they resisted the idea that there was symbolism or that there were themes discussed, or even that there were patterns or that there was intentional structure to things. They want it to be a newspaper from a fictional universe. They don't want it to be a story. They want it to be factual.

I don’t think most readers fall into those traps. But I do fear that “hard worldbuilding” rules—which have made their way out of SFF fandom and into everything from MFA programs and commercial fiction how-to guides—can leave both readers and writers unable to delve in the pleasures and opportunities that other modes of worldbuilding can provide. Certainly, I frequently hear other types of work dismissed as sloppy, lazy, or “bad at worldbuilding.” Most complaints about how novels—especially so-called literary speculative novels—fail are on these CERB grounds. “The Road doesn’t explain the apocalypse!” “The world of The Underground Railroad isn’t consistent!” “The magic in One Hundred Years of Solitude doesn’t follow any rules!”

Here’s what I think such readers are missing:

Other Ways to Building Worlds

I agree with the common SFF world irritation at realist writers who decide to slum in science fiction or fantasy without, to quote Selonick, “thoughtful engagement with the traditions or history of the genre.” This irks. Honestly, I find myself less annoyed by such writers than by the surrounding critical praise that often acts as if some literary author is the first to do X, Y, or Z when the novel is closer to the one millionth book to do so—and is doing it much worse than books shelved in SFF!

But. I fear that many who make this complaint commit the same sin by flippantly dismissing works for “failed” or “lazy” worldbuilding when in fact those works fall into their own long and rich literary tradition. You can trace a clear lineage from European writers like Kafka, Schulz, and Kubin and the Surrealists to magical realist Latin American writers like Márquez, Cortázar, and Borges through the 60s/70s American postmodernists like Barthelme and Pynchon to many of the speculative literary fiction writers working today. We could add in an infinite number of authors here, including many from outside of Europe and the Americas of course (e.g., Ben Okri, Kobo Abe, Can Xue, Yoko Ogawa, etc.). We could even trace it all the way back to the earliest fairy tales and ancient myths—those are rarely logical or consistent in their worldbuilding after all.

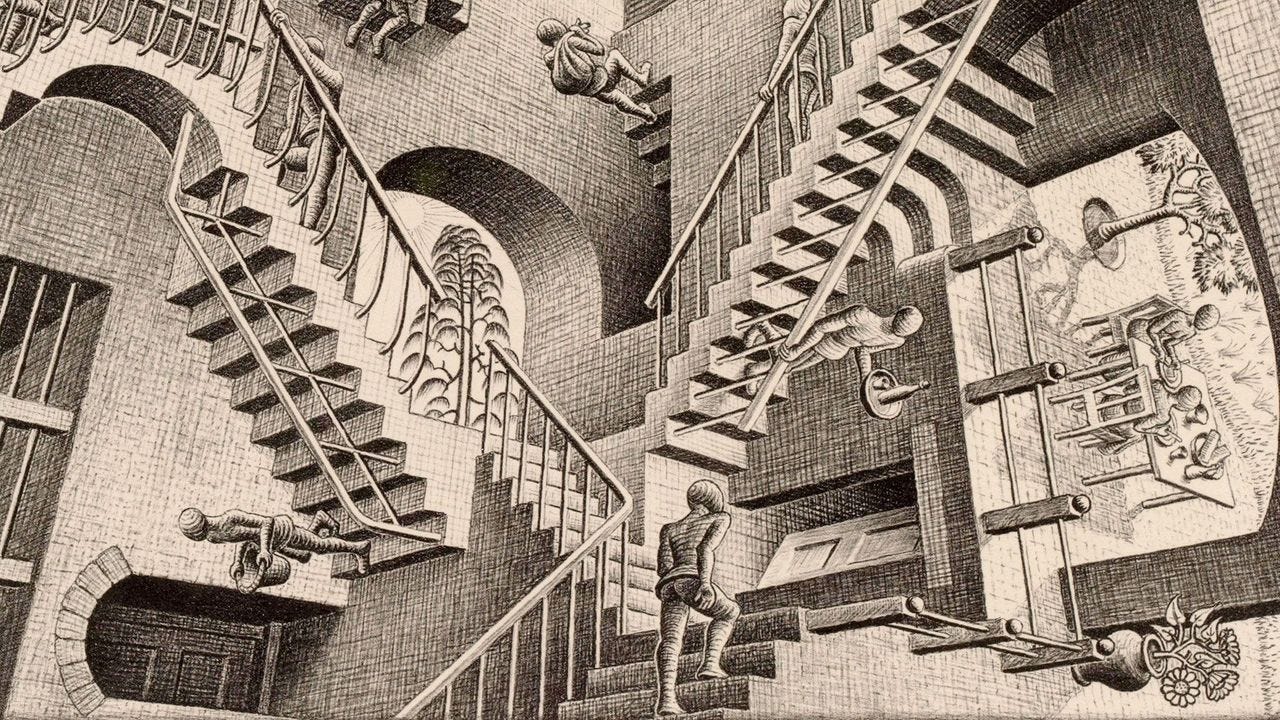

The surreal. The fabulist. The magical real. These methods of worldbuilding don’t “fail” at hard worldbuilding. They’re doing something else entirely—and something you cannot do with hard worldbuilding. Surrealism cannot be consistent by definition. Magical realism mingles the magical with the mundane in a way that would not work if the magic was rules-based. The minimalist world of a fairy tale clashes entirely with the detailed, lore-heavy realms of epic fantasy.

My point here isn’t that any one method of constructing a world is better or worse than another. Only that each presents different opportunities and limitations, unique possibilities and constraints. Kafka’s The Castle would not be improved by detailed lore of A Song of Ice and Fire. One Hundred Years of Solitude could not be written by Brandon Sanderson. Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities couldn’t exist with consistent rules.

Obviously we can have a taxonomical debate here. Should surrealism be considered a subgenre of fantasy or not? Is it only magical realism if the writer is from the global south? Should the label “speculative” be reserved for traditional SFF genres? I won’t wade into all that here. I will only insist that these other traditions are equally valid traditions and ones that work by different methods.

SFF Didn’t Always Care about Worldbuilding Anyway

I fear it sounds like I’m arguing that hard worldbuilding is for science fiction and fantasy and other modes are for literary fiction. I do not think this is true, especially not historically. There have been plenty of great surreal or fabulist SFF works like Dhalgren and Gormenghast. The entire mode of “weird fiction,” in both old and New Weird varieties, embraces the surreal and inexplicable. Indeed, much of horror fiction—traditionally grouped with SFF—doesn’t follow these rules.

If you read Golden Age science fiction, there is often little focus on either detailed lore or consistent, logical rules. Some of the greatest works of classic science fiction, like Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles, are completely inconsistent chapter to chapter (perhaps in part because many, like The Martian Chronicles, were “fix-up” novels made by combining short stories). Classic SFF writers like John Wyndham, Kurt Vonnegut, and Isaac Asimov would be roasted alive by a modern SFF reviewer for their lack of worldbuilding explanations or consistent rules. When did it all shift? In fantasy, perhaps it all comes from the long shadow of Tolkien’s lore-heavy books. In science fiction, you start to see more attention to coherent universes and rigorous exploration of technology during the New Wave. But even as recently as the 80s, authors like William Gibson seemed unconcerned with hard worldbuilding. (Gibson on meeting with RPG makers interested in adapting Neuromancer: “They set me down and questioned me about the world. They asked me where the food in the Sprawl comes from. I said I don’t know. I don’t even know what they eat. A lot of krill and shit. They looked at each other and said it’s not gameable. That was the end of it.”)

I suspect one source is the rise of creative writing courses, both in academia and outside of it. Many students come to classes looking for simple rules to follow and many professors default to them because rules are easy to explain and make your advice “actionable.” “Well, actually there are infinite ways to do X…” is a harder sell than “Jot this down, Johnny. X requires A, B, and C and that’s that.” But I suspect much of the preference for hard worldbuilding doesn’t come from SFF literature itself really. I think it may come from gaming culture, whether tabletop RPGs like Dungeons & Dragons or miniature wargames like Warhammer 40k or video games like World of Warcraft, where rules are required for the game to function and the (ever-expanding) lore is both a major part of the appeal and a requirement for ongoing commercial viability. Gotta keep those expansion packs rolling out after all. A similar logic governs corporate SFF franchises with their endless spinoffs and sequels.

I also assume it comes from fan culture—especially as amplified by the internet—where nerds get together to overanalyze everything they love. Again, I grew up in nerdy circles. I get it. One of the most popular pastimes in SFF circles is going off about worldbuilding problems, whether amusingly pointing out that “meat’s back on the menu, boys!” implies orcs have a dining culture or spending time coming up with “fan theories” for this or that alleged worldbuilding issue. I cannot think of a single popular SFF franchise or series that hasn’t spawned long-winded and not-necessarily-wrong worldbuilding critiques. Star Trek, Game of Thrones, Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, you name it.

But here I have to make one final observation. Doesn’t the fact that every popular franchise has “worldbuilding problems” prove that no one really cares about worldbuilding problems—or for that matter plot holes or flat characters or any other alleged literary sin—as long as the work is good?

My new novel Metallic Realms is out in stores! Reviews have called the book “Brilliant” (Esquire), “riveting” (Publishers Weekly), “hilariously clever” (Elle), “a total blast” (Chicago Tribune), and “just plain wonderful” (Booklist). My previous books are the science fiction noir novel The Body Scout and the genre-bending story collection Upright Beasts. If you enjoy this newsletter, perhaps you’ll enjoy one or more of those books too.

I think we will look back on Sanderson as the origin of a real paradigm shift in fantasy. There seems to be a flattened version of how Sanderson writes his stories due to his popularity and lecture series, similar to what happened the 70s and 80s. We saw clones of Tolkien who copied his plot structure, world elements, and themes, then a reaction to that which brought about the likes of Martin and grim dark fantasy, the hard world-building is having it's moment.

LitRPG and progression fantasy, blurbs about magic systems, and shared universes seem to be everywhere. These are the natural extension and simplification of Sanderson's works. I suspect in 5-10 years grounded, very soft magic, and a greater focus on small slivers of a world will become common.

It's hard to know for sure, though, since every fantasy fan knows how broad and diverse the genre is in practice and every niche is represented somewhere. So perhaps the real outcome will just be balkanization. Also, if the booksellers are the guide then Romantasy is the real winner right now, but in my eyes that's it's own genre at this point.

This ties in with your previous post about how many fiction writers today are writing fiction like they're transcribing a movie or TV show and try and include every detail the viewers' eyes would catch in the setting if they were watching a movie. But, in fiction, it just gets super-boring to read too many details about a setting while waiting for the meat of the story.