Fantastic Modes; Or, Is Magical Realism Just Urban Fantasy?

On the differences and similarities between surrealism, fabulism, contemporary fantasy, and etc.

Hello, readers. Last week, I published an original work of fiction in this newsletter called “Algorithm America.” If you missed it, I hope you’ll give it a read. It’s about A.I. novelists, LLM therapists, algorithmic policing, and other ripped-from-the-headlines-but-slightly-science-fictional things.

This week, I’ve been mulling a question that came up in some recent literary discussions: isn’t magical realism just urban fantasy by another name?

This is a question I’ve seen a lot. And there’s a common claim that works in the magical realist/surrealist/fabulist zone are “really just fantasy” for literary snobs. Or as Terry Pratchett once put it, “a polite way of saying you write fantasy.” To the degree this is critiquing artificial barriers to bar certain fantastic fiction from “real literature,” I agree. I read and write SFFH (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) alongside so called “literary fiction.” So I certainly agree many great fantasy-shelved writers have been unfairly overlooked by literary critics.

But if we’re trying to illuminate fiction—to understand how different storytelling styles operate—then the claim that magical realism is simply urban fantasy by another name doesn’t seem right to me. Especially since this claim often comes with its own snobbery. A few years ago, I was discussing this with a SFF writer who insisted magical realism was really fantasy yet in the same breath mocked it as lazy writing by authors who “don’t think through their worldbuilding.” Suddenly magical realism wasn’t just fantasy by another name but bad fantasy by another name. I’ve heard this a lot and, well, disagree. Magical realism operates differently, not in the same way yet worse.

Increasingly, I’m inclined to think less in terms of “genres” than “modes.” Something about genres promotes a partisan mindset where the goal is to “win” by either declaring the superiority of your preferred genre or claiming territory from other genres. This writer is “really” science fiction, that writer has “transcended” genre, etc. It’s more obfuscating than illuminating. If you want to argue surrealist and magical realist work should be shelved with fantasy, or that fantasy should be shelved with literary fiction, that’s fine. I’m not arguing about that here.

Instead, I’m going to look at what I see as the differences between magical realism and urban fantasy as modes of storytelling.

A Few Caveats

Like most literary labels, magical realism is a fraught term. Originally coined in German for a style of visual art, in literature it is historically associated with Latin American literature around the Boom Period. Many argue the term should be reserved only for Latin American writers. I think that’s a fair argument. Others claim the term should be extended to any non-Western country (even if that country itself was a colonizer, like Japan) or else any author of sufficiently marginalized status from any country. OTOH, there are claims that the term itself is marginalizing—excluding POC authors from the more popular fantasy bookstore section—and many Latinx writers have noted the problematic habit of calling all non-realist literature by Latinx writers “magical realism” even when they are writing something like Gothic horror or high fantasy.

I won’t pretend to be in a position to adjudicate all this. I don’t label my work magical realist. But I take a descriptivist approach to literary terminology and (rightly or wrongly) magical realism has become a term applied to writers from around the world. “Surrealist” and “fabulist” are two alternative terms that are often treated as synonyms, although in my reading the former lacks the “realism” half of magical realism and the latter implies a fairy tale style and structure that isn’t always present.

Urban fantasy is less fraught although we might question the “urban” modifier. If you look at the Wikipedia page—again, I’m interested in how people commonly use terms—you see works set in rural areas or small towns such as Stephen King’s ‘Salems Lot. Does anyone believe an urban fantasy novel changes genres when a character steps outside the city limits? The alternative umbrella term, “contemporary fantasy,” is rarely used and too easy to confuse with “recently published fantasy.”

For this newsletter, I’m going to go with the common terms here but when I say magical realism you can mentally sub in surrealism and fabulism, and when I say urban fantasy you can mentally swap in contemporary fantasy.

Historical Origins

Literary modes (or genres) are always historical and contextual, and I think we we understand them better knowing the lineage.

Urban fantasy is a strain of SFFH that more or less developed alongside the other strains. It has origins in 19th-century Romantic fiction, Gothic fiction, dime novels, and pulp magazine stories. The idea of urban fantasy as a distinct subgenre seems to be a 20th-century phenomenon with roots in the horror boom of the 1970s/80s (e.g., King and Rice) and authors who combined fantasy with detective fiction (e.g., Glen Cook) that—I suspect—are a reason the genre is associated with gritty urban settings. I think you can also see an influence from comics (e.g., Gaiman’s The Sandman and Hellblazer) and, as far as consumer popularity goes, fantasy TV shows like Buffy and Supernatural. Basically, urban fantasy comes out of SFFH mixing together elements of fantasy, noir, and horror while working in the traditions of those genres.

(Side note: what separates urban / contemporary fantasy from horror? Aren’t Supernatural and ‘Salem’s Lot horror? This is something of a vibes question. Readers and viewers will have their own judgement about where that line is drawn and often the answer is “both.”)

Magical realism’s lineage is different. The predecessors (or early examples if you prefer) include early 20th-century writers like Franz Kafka and the Surrealists. Latin American magical realists such as Borges, Carpentier, and Márquez spoke openly about their influence. (Márquez on Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis”: “When I read that [opening] line I thought to myself I didn't know anyone was allowed to write things like that. If I had known, I would have started writing a long time ago.”) Scholars also tend to say magical realism flourished in Latin America as a rejection of Western realism as well as a fusion of European literature and indigenous mythology. There’s also an influence of earlier experimental Latin American literature. From these influences you can see magical realism’s political dimension as well as its focus on estrangement through unexpected and original magical elements akin to Surrealist art. More on that below. With the boom period, magical realists like Márquez’s became world famous and their influence is obvious in certain strands of postmodernism (e.g. Barthelme and Rushdie) and fabulism (e.g. Russell and Calvino).

So how do these differences manifest on the page?

Magical Mundanity vs. Magic Hiding Behind the Mundane

Both magical realism and urban fantasy can be said to add the magical to the mundane, but there’s a difference in how this is approached.

In urban fantasy, the magical is typically hidden within the mundane. In works like the Vampire Chronicles or the Dresden Files or American Gods, magical and supernatural entities are common yet secret. The magical may influence or even control our reality—hidden councils of fairies or wizards are behind our wars, disasters, and triumphs—but the average human is unaware. The life for most people is our life. Thus the reader enters with our understanding of our reality, then is granted a peek behind the veil. This concept, used in other SFF genres as well, is sometimes called “the masquerade.” Outside of the hidden magical world, the real world operates like ours. NYC is NYC, unless you’re one of the select few that know the fae dwell in Central Park.

Some urban fantasy works tweak this formula, such as True Blood / The Southern Vampire Mysteries depicting a world where vampires have ended the masquerade and recently become known to the public. But even in these works the magical is typically separate from the mundane. The supernatural is confined to certain creatures, locations, and/or objects.

In magical realism, the magical isn’t hidden or separate from the mundane but rather completely intermingled. The magical events that appear in the works of writers like Gabriel García Márquez, Salman Rushdie, and Karen Russell are features of the world. Any character living in Macondo, say, will witness and may be involved in the magical events. There’s no masquerade. At the same time, the real world itself becomes magical. NYC isn’t just NYC. The subways are pulled by giant rats and billionaire’s park their helicopters in the clouds, or whatever. This happens both at the “worldbuilding” level and at the stylistic level, with authors describing banal events in magical ways and vice versa. A classic example might be found in the opening of Márquez’s “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings,” where everyday banalities like rain and a beach are described wondrously—“The world had been sad since Tuesday” and “the sands […] glimmered like powdered light”—while the on-the-surface astonishing appearance of an angel is described rather unmagically: “There were only a few faded hairs left on his bald skull and very few teeth in his mouth, and his pitiful condition of a drenched great-grandfather took away any sense of grandeur he might have had.”

(This mingling also leads to useful confusion about when something magical is actually happening or not. Is the world literally sad since Tuesday? Or is it just a poetic description of a days-long rainstorm? It could go either way.)

As a fantasy genre, the narrative weight of an urban fantasy story is the magical—Interview with a Vampire is a lot more about vampires than it is about interviewers. By contrast, magical realism is often framed as giving “equal weight” to the magical and the mundane. An everyday problem like a couple’s dissolving marriage is often the focus, even while wild events and impossible imagery swirl in the background.

This also seems like the place to note magical realism’s common political dimension. In Latin American magical realism especially, the mingling of the magical and the mundane is often argued to reflect the experiences of issues like political instability, colonialism, and rapid change. E.g., the unreal elements of the dictator in The Autumn of the Patriarch reflect the unreality of living under such real-world dictatorships. This obviously isn’t to argue urban fantasy can’t be political. It’s just the political critique functions differently in the context of “the masquerade.”

Systematic Worldbuilding vs. Dream Logic

Here we see an obvious effect of the different aesthetic lineages. Urban fantasy tends to operate with traditional SFF worldbuilding logic. There are rules for magic. If you put on an invisibility cloak, you turn invisible. If you are bitten by a werewolf, you become a werewolf. Etc. Obviously in fantasy nothing is purely logical, but there are explanations and lore and an explicit or implied system to explain the magical and supernatural. These serve clear narrative functions such as determining the stakes of the story. Can the hero acquire object X needed to defeat villain Y? Etc.

Magical realism operates with more dreamlike or surreal (il)logic, as one would expect from the influences. Systemized rules or even explanations are intentionally avoided. Gregor Samsa simply wakes up one day as a beetle. Cortazar’s narrator in “Letter to a Young Lady in Paris” simply begins vomiting bunnies. When an explanation is given, it is one of a distinctly illogical and poetic nature. In Márquez’s “Light is Like Water,” young boys flood their house with liquid light by breaking lightbulbs. The narrator provides the logic for this bizarre event, saying that he once told the boys “Light is like water…You open the tap, and out it comes.” It’s almost a joke.

Perhaps another way to think about this difference is that the magic in urban fantasy is universalized and systematized. The rules of vampirism in Anne Rice’s novels apply to all humans and all vampires. Magic in magical realism, on the other hand, is often localized. In One Hundred Years of Solitude, a priest sips hot chocolate and is so overwhelmed by the taste that he levitates. This is a singular event. It isn’t magical hot chocolate that makes everyone levitate. The priest won’t levitate when he sips again or drinks anything else. Why does Gregor Samsa turn into a bug? Perhaps because he is so alienated or perhaps by random, but there’s no indication that anyone else might ever turn into a bug in that world.

This difference is the root of the “magical realism is just bad fantasy that doesn’t think through its worldbuilding” critique. But magical realist writers are intentionally adopting a surreal logic and chaotic magic to create specific effects.

Using vs. Avoiding Established SFF Concepts

The obvious reason urban fantasy is grouped with other fantasy subgenres is that it works with established SFF tropes. Wizards, the undead, mythological creatures, Lovecraftian entities, etc. It uses the literary language of SFF, just set in an otherwise real-world setting instead of a mythologized past or a “second world” realm. Note that I’m not saying urban fantasy writers are less creative or more formulaic. There can be tremendous inventiveness in deploying established concepts in new ways. Indeed, that’s a prime pleasure of genre.

Magical realism is speaking with a different literary dialect, and you rarely see the traditional mythological and fantasy creatures appear unless they’re subverted dramatically such as Márquez’s dirty old man buzzard-angel. Similar to how Surrealist painters rejected established visual symbolism in favor of their own individual symbols, magical realists tend to look for new images and ideas that aren’t laden with the expectations of established tropes. Imagine if Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis” opened “As Gregor Samsa looked at the full moon one night he found himself transforming in his bed into a werewolf.” It’s not that Kafka’s “The Werewolforphosis” couldn’t be a great story. It’s only that by including an established creature with established lore, the story would operate in a different terrain and readers would come in with different expectations.

The distinction being made here is—to speak in SFFH terms—akin to the distinction between “weird fiction” and other horror fiction. There’s a robust body of scholarship on how the mode of weird fiction creates different effects by its avoidance of established horror creatures.

Exceptions, Overlap, Etc.

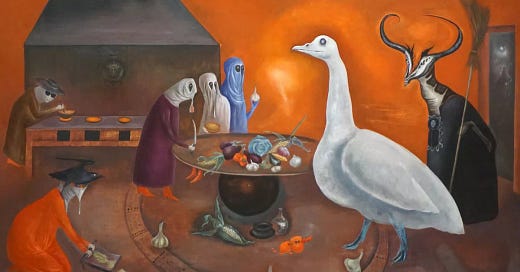

I mentioned above that surrealism and fabulism are often treated as synonyms for magical realism, which is fine. If we’re to distinguish them a bit I’d briefly say that surrealism is less tethered to the real world. It isn’t our world turned magical but the author’s own world of dream logic and unreality. This is quite hard to sustain over a novel imho, but it can be done. Examples include the works of Leonora Carrington (a surrealist painter as well, see painting at top), Duplex by Kathryn Davis, and Kangaroo Notebook by Kobo Abe. Fabulism implies a fable / fairy tale style and structure or else a remixing of traditional fairy tales themselves. Examples include most of the works of Helen Oyeyemi, many Italo Calvino works, and Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber. But these distinctions are small.

Obviously there are examples of urban fantasy with some magical realist elements or magical realist works with some urban fantasy elements. As I mentioned, True Blood removes the masquerade but is otherwise a traditional urban fantasy work (established vampire lore, logical worldbuilding, clear rules, horror tropes, etc.). Many Haruki Murakami novels involve an everyday character discovering hidden strangeness, but operate with a magical realist style and surrealist logic. Modes of storytelling are often more about “vibes” than checklists.

We can also always come up with borderline cases and boundary-blurring stories. For example, classic magical realism—at least in the novel form—tends to have a lot of magic. There are countless unrelated magical elements in Márquez’s novels. But more recent fiction that has been labeled magical realism, such as Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad or Hamid’s Exit West, center on one magical change to the world. Are these still magical realist or do we need a new term (magical minimalism?) to distinguish the modes? What about weird fiction writers like China Miéville who write in SFFH traditions but with a healthy does of surrealism? Or on the flipside Kathryn Davis’s Duplex, which comes from a very clear surrealist tradition but includes some SFFH tropes?

This isn’t science. It’s art. Modes of storytelling exist on a spectrum. They aren’t distinct categories that never overlap.

But at either end of the urban fantasy / magical realism spectrum—say the Dresden Files on one side and One Hundred Years of Solitude on the other—the modes are quite distinct, with different possibilities and limitations. They are certainly at least as distinct as the various subgenres of SFF (high fantasy vs low fantasy, solar punk vs steam punk, etc.) or other literary labels (Young Adult vs New Adult, autofiction vs. dirty realism, etc.) that people have less trouble distinguishing.

From a writing point of view, the main thing is to understand the mode you want to write in. A systematized magical world has very different effects and constraints than a surrealist world and vice versa. Working with established lore brings different expectations than trying to come up with new ones.

The question is always what works best for the specific story you want to tell?

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.”

Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

This is an excellent article, and I really appreciate your deep dive onto the subject. I learned a lot about the histories of different genres, and I agree with your origins of urban fantasy.

One small note, and it's mostly a nitpick -- Alan Moore never wrote Hellblazer, he just created the character John Constantine. The most famous writers of Hellblazer (and there were a lot, the thing ran for 300 issues) are John Delano and Garth Ennis (who also wrote the comics The Boys and Preacher). Moore's John Constantine would be more accurate, he is a prototypical urban fantasy wizard, but when Moore wrote Constantine, he actually appeared in Swamp Thing (which is very much in the mix of horror / southern gothic / urban fantasy you're talking about).

I appreciate the delineation. One thing to add is that, for the writer, the choice of genre and adherence to the tropes and rules thereof is in large part a marketing decision, as that’s what the genres do in book selling sites -- give readers a way to find the kind of stories they want. You can always write what you want, of course, but if you can’t state what the genre is, and make the readers who love that genre happy, it’s a lot tougher to sell a book.