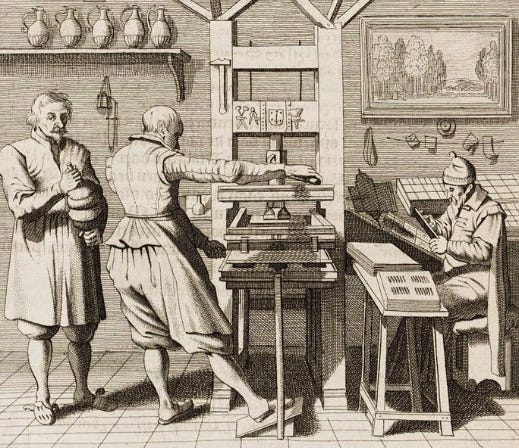

Interview: Editor Sean deLone on How Modern Publishing Actually Works

A conversation about the evolving role of editors, how books get "into shape," and the good and bad of publishing today

Recently, I did some Counter Craft reorganization and archived posts are now arranged into categories on the homepage. Two of those, Interviews and Publishing Demystification, are ones I’ve been meaning to expand by including interviews with agents, editors, and other people working in publishing. I thought a great way to kick that off would be by interviewing my excellent editor Sean deLone, who not only helped shape up my novel Metallic Realms at Atria Books but runs a very smart Substack called “Dear Head of Mine” that does a great job demystifying a lot of publishing questions from an editor’s POV.

DeLone’s recent article “The Three Jobs of the Modern Editor, or 36 Plates” got a lot of deserved attention here. This piece gives an honest and detailed look at the many tasks a modern editor takes on. Any authors who are curious about the work big publishing editors actually do should give it a read. I followed up with deLone about that article, the evolving role of editing, if there are too many books, and the general state of publishing books:

Your recent Substack article “The Three Jobs of the Modern Editor, or 36 Plates” is admirably candid about the evolving work of being an editor. Writers love to complain about how many plates we juggle—I’ve done my share of grumbling—but as your article explains, the same is true for editors. Could you summarize what the 36 plates are?

I was asked the question editors often are from a non-publishing friend: how many books are you working on right now? I’ve always struggled to answer that, but the metaphor of balancing 36 plates finally struck me. The 36 plates are: the 12 books that are publishing this year (already edited but need to be managed), 12 publishing the next year (editing/preparing them to be published), and the final mystery 12 coming out in 2 or more years (these are writers the editor has to go find and sign up/encourage their existing authors to write more books). The overall number is nothing to sneeze at, but the difficulty is more so that editors are doing three totally different jobs on three different timelines.

I think sometimes writers hear an editor publishes ~12 books a year and thinks “that is only one book a month!” But really, you’re working on many books in various stages of the process as well as “air traffic controlling” (to use your metaphor) between author, agent, production, sales, etc.

I’ve heard that in some countries, including I think the UK, the job is often split in two. You have an acquisition editor (who acquires and does structural edits) and a desk editor (who does project management and line editing). Do you think that model would be preferrable? Or is it ultimately recreated in the US in many cases by assistants doing much of the latter work?

I hadn’t heard of that, it’s an interesting idea. It’s tough, as much as it makes sense to split the jobs up for pure workload considerations, there’s something incredibly intimate about the relationship between editor, writer, and publication that I do feel would be lost. Every process informs the next—how the book is shaped and the conversations in the editorial process inform how we “project manage” and constantly work to communicate what is special about the work. It would be so strange to “hand off” your author to a different editor after the first stage. But I might only be resistant to it because that’s not my experience, clearly a lot of editors prefer one aspect of the job over others so it kind of makes sense if you take a step back.

As for assistants, you’re spot on. Best case scenario, they shadow the editors they work for and basically do some part of every piece of an editor’s job to relive the weight—communicate with authors, project manage, edit, etc. In that sense we’re already doing something very similar (although most assistants assist 2-3 editors at once), it’s just very clear with editor/assistant who makes the executive decisions at the end of the day, I imagine that could get blurrier in the situation described above.

A consequence of the plate juggling is that editors spend less time actually editing. At the same time, editors do still edit. I can testify that you and I went through several rounds of (necessary) edits on Metallic Realms. Is there a type of editing that editors cut back the most on? Is there less line editing than larger structural edits, for example?

Every editor would answer differently, but for fiction my process is always to start with the biggest edits—conceptual, structural, thematic—and work my way “down” to smaller edits (line editing, more subtle character and plot work) in subsequent rounds of editing. As a result, just because of time, it’s the fine work that usually suffers. I try to balance this out by working with writers (like you) who know their way around a sentence so that we can use the majority of our time to tackle the big stuff. Although part of me wishes I could lock myself in a room and chisel away at sentences for weeks at a time.

Other editors have different philosophies and see intense line work as their primary job. Also, there are plenty of exceptions. I just worked on a translated novel, which consists of primarily line editing since the author has a native editor and it’s understood that the story is more set in stone since it’s already been published elsewhere. In nonfiction, oftentimes the ideas and structure are more straightforward but the line-editing can be endless to get a sharper articulation of the story and/or thesis. Still, it is the case that we often do fewer rounds of editing than is ideal. If the publication is especially timely, you might get one or two cracks at the manuscript, max.

A consequence of editors having less time to edit is that agents are increasingly expected to do a lot of editing. (And I’d extrapolate that agents, who are also overworked and juggling many things, are probably increasingly looking for manuscripts that are already “in shape.”) What advice would you give to writers who are looking to query or go on submission in terms of getting the manuscript “in shape”?

Editing starts with the writer, and my advice to writers would be to take the book or proposal as far as you possibly can yourself before querying or turning it into your agent—edit, sharpen, get feedback from trusted readers, repeat.

Many agents are amazing editors, as good if not better than editors at publishing houses (writers: utilize them). Only, their editorial role is often quite different. They do a lot more developmental editing these days than editors do, which means they help writers through rougher stages of creative development than an editor typically has to (write this novel, not that novel; throw this character out; change the time period, etc.). The “in shape” standard is higher than ever and agents often get their fiction manuscripts in “publishable” shape before they even send them to editors.

This might be an unkind way to say it but I often think of the publishing editing pipeline as a “garbage in, garbage out” kind of process. Mistakes compound from writer, to agent, to editor, but then again so do strengths if everyone in the chain is putting forth an intensity of effort. There’s a bit of a natural impulse to get to “finished” and hand it off to the next person (including editors trying to hand it off to production), but if the writer/agent/editor cuts corners because they expect someone else to fix it later, things usually turn out poorly.

There’s a bit of a natural impulse to get to “finished” and hand it off to the next person (including editors trying to hand it off to production), but if the writer/agent/editor cuts corners because they expect someone else to fix it later, things usually turn out poorly.

As you know, I’m someone who thinks a lot about genre and the differences (real or illusionary) between “literary fiction” and “genre fiction” and other categories. My impression is that the boundaries between these categories are crumbling even within publishing. Specifically, I mean that an imprint like Atria Books—and we could name many others here like FSG, Riverhead, etc.—will publish both books that might be shelved as science fiction or as literary fiction. In that past, that might not have been the case.

How does the question of “genre” look from inside publishing?

It’s definitely crumbling. You said in one of your newsletters that genre blurring is the biggest development in 21st century in terms of fiction—even though autofiction has been talked about more. I completely agree with you. So do readers. The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley is a good example from last year—it’s a book club book, it’s got elements of a literary novel, it’s a sci-fi novel. At Atria, we have a bestselling novelist Rebecca Serle who blends elements of magical realism and rom-com with women’s fiction. It’s no longer an outlier that successful books, critically and commercially, have their toes in multiple genres and readerships. The literary world is embracing these kinds of books where they once were shunned. Writers and the general readership are expanding their appetites for genre. So, if readers are more open to breaking down these distinctions than ever, so are editors and publishers.

This makes me wonder about the question of imprint identity. Does the colophon1 mean less to reader’s these days?

Colophons have always meant very little to actual readers historically and I don’t think they mean much now either. Most normal readers can’t even name the big publishing companies, even fewer can name an imprint, and yet even fewer an editor. Publisher/imprint/editor identity matter (somewhat) inside the industry—to booksellers, writers, media, influencers, etc.

Publishers/imprints/editors build reputations by publishing good books and after a number of good books industry insiders know who is doing good work and begin to trust that the next thing they do will be good, too. In my opinion, there’s only one publishing imprint that has ever built such a literary and commercial reputation that it could be considered “a brand” in the traditional sense, but even that brand waned once they stop putting out high quality/popular books consistently and at a high clip. It’s not easy to constantly put out blockbusters and works of literary genius year after year that stand out in a sea of books. Such that these reputations are hard to build and rarely ever last. There was a red-hot imprint when I first joined publishing that every aspiring editor and writer wanted to be a part of and its allure has slowly faded since. It’s that old adage “it takes years to build a reputation and a day to destroy it.”

Here is a spicier question. One thing I hear many people in publishing, including writers, argue is that publishing should publish fewer books. Everyone in publishing is overworked with too many duties and too many titles to support effectively. From the writer’s POV, there are too many titles competing for readers. Do you think publishing would be better off if fewer books were published? And do you think this could ever happen?

This is very spicy. It also breaks my brain a bit. If you count every publisher and every form of publishing (i.e. self-publishing), we’re in the millions of new books, every year. That’s way too many.

But as far as traditional “Big 5” publishing, we’re in the 10,000s of new print books a year. A big number, but not insanity when you start chopping it up by category—cookbooks, self-help, novels, etc. If big publishing decided to shrink and focus, I think the result would sadly be even fewer chances for midlist authors and less room to take chances to build careers with authors who aren’t instantly commercially successful. Are there too many books? On an individual level, I’ve always thought of myself as an editor with a high standard, especially looking for books with both high literary value and commercial potential. I thought my list would be small as a result—how many great books can truly be out there?—but then you keep finding great stuff. Readers kind of feel the same way, I think.

The best metaphor is probably television—there is definitely too much of it, and yet there’s so much good stuff you can’t even watch everything that’s worth seeing. It’s the same with books and ultimately that’s really good for consumers. The frustrating part is you feel overwhelmed with paralysis because you don’t know what to watch or read in a sea of stuff (lots of it is pretty mediocre), which is a real problem. Another result of a highly fractured consuming experience is we lose conversation, community, and shared experiences—“Have you seen Severance?”, “No” (paraphrasing a conversation I think we’ve had) is a fairly deflating human interaction. But if we went back to how it used to be and shrunk the offerings, I think we’d just have a dozen shows like Reacher, Tracker, and High Potential, not a dozen shows like White Lotus, Succession, or The Studio.

This seems right to me. In theory, fewer books might be good, but in practice you have to assume publishers would keep the commercial fiction and celebrity books they know will generate revenue and cut the things—poetry, literature in translation, challenging novels of any kind, etc.—that rarely become bestsellers. The issue then becomes one of discoverability, which is also a big issue in TV, from what I understand. What advice would you give to writers for how to best position their books to be discovered? Is having a social media “platform” still the best advice?

“Platform” might be up there for me with “vibe” as most recklessly tossed around words these days.

There are books authored by people with 5 million plus Instagram followers that can’t sell 5,000 copies. Then there are literary novelists with 1,000 Twitter followers that sell a million copies. Some platforms translate to sales and others don’t. It’s difficult to pinpoint what matters and what doesn’t. The thing you can control most obviously as a writer is foremost the quality of the book you’re writing and identifying a type of story or subject that other people might want to read about.

I’d advise writers to think about how the platform they’re building fits in with the book they are writing and what comes naturally to them. If you’re writing a nonfiction book, build your expertise and connections in a field—that’s a platform. If you’re a literary novelist, be part of a literary community. If social media comes naturally, do that of course in a way that feels authentic. Also, I’d say it’s more about connecting with the right people with whom your book will resonate, who will become your biggest promoters, rather than getting the most eyeballs by chasing social media stardom.

There are books authored by people with 5 million plus Instagram followers that can’t sell 5,000 copies. Then there are literary novelists with 1,000 Twitter followers that sell a million copies. Some platforms translate to sales and others don’t. It’s difficult to pinpoint what matters and what doesn’t. The thing you can control most obviously as a writer is foremost the quality of the book you’re writing and identifying a type of story or subject that other people might want to read about.

Another thing I hear many writers and agents decry is the decline of the midlist. (You recently wrote about midlist books here.) Publishing seems to increasingly work on a blockbuster model where most of the advance money goes to a few big bets and everyone else gets a small advance. Similarly, book sales are either huge or small. The midlist, books with decent but not huge advances and decent but not huge sales, is disappearing.

Does this seem correct to you? And if so, could anything reverse the trend?

The blockbuster model of publishing is definitely real and probably more prevalent than ever. Success or failure of a blockbuster novel also gets lots of attention, creating a feedback loop publishers chase, because related to your question above, they are struggling in any way to create “buzz.” It’s easier to make an industry story out of “million-dollar novel” than an editor saying their novel with a modest advance is a “heartbreaking work of staggering genius.”

But the midlist is publishing’s lifeblood, and also where a lot of huge bestsellers come from. Just at Simon & Schuster where I work there’s Anthony Doerr, Fredrik Backman, Taylor Jenkins Reid, all blockbuster authors now, but they didn’t start their publishing careers as part of a blockbuster model. They were midlist authors who “broke out” after publishing a number of books. Nothing is more gratifying for an editor. Incidentally, it’s also the way most editors start out—it’s rare you get handed a million dollars to go buy an unknown novelist out of the gate. So, while what you describe is true and worsening, it’s still the case that small advances one year can turn into big advances the next. It’s not pretty but as long as that mobility exists there’s still hope.

To reverse the trend of winners-take-all publishing we need to invest and keep building our reading culture—your next question actually encompasses many of the things I would suggest to keep expanding on. But the gist of it is we need readers who are more active in book culture so that it’s not just 5-book-a-year readers getting pointed to the same three “sure things”, but people really getting involved, developing their own taste and willingness to take chances.

I’ve asked about some downer things (declining midlist, overworked editors/writers/agents, etc.). What are some positive trends you see in publishing today?

Independent Bookstores. The indies are as strong a sales and cultural force as ever. They are real communities and real people. As a publisher, direct relationships with booksellers are one of the rare instances where things feel in your control—we can forge connections to the people that actually hand-sell our books to readers. I’ve become a fan for life of many authors by going to indie bookstore events (and they’re often free to attend).

Book clubs. There are big book clubs like the celebrity ones and the Book of the Month service, both of which bring tons of people to books. But also, it feels like this reflects the larger cultural trend of people—young women in particular—starting their own book clubs with friends and friends of friends. It’s super encouraging.

Niches. The Mysterious Book Shop in Manhattan has been around for a while. But now there are tons of romance-themed bookstores like The Ripped Bodice in Brooklyn and The Twisted Spine, a horror-themed bookstore opening soon (sorry, this is very New York centric but there are lots of these kinds of stores throughout the country opening as well). There are also lots of subscription boxes that specialize in specific genres (stay tuned Lincoln Michel fans!). These reach tons of readers in a different way. I love the creative ways publishing is getting more bespoke to cut through the noise.

Finally, I’ll say that writers are still here and putting out amazing stuff. As much as I have kvetched about editor overwork, writers have the hardest job in publishing and it’s not even close (and they are also often doing several jobs, as you wrote about recently). I’m just so grateful that in our frantic, scary, distractable world, there are writers battling all these obstacles to give us great stories.

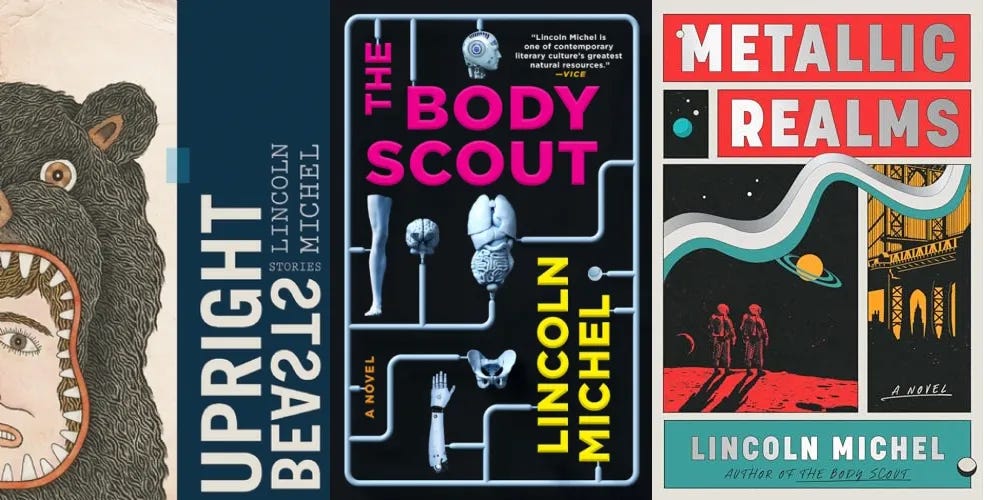

My new novel Metallic Realms is out in stores! Reviews have called the book “Brilliant” (Esquire), “riveting” (Publishers Weekly), “hilariously clever” (Elle), “a total blast” (Chicago Tribune), and “just plain wonderful” (Booklist). My previous books are the science fiction noir novel The Body Scout and the genre-bending story collection Upright Beasts. If you enjoy this newsletter, perhaps you’ll enjoy one or more of those books too.

Industry term for the publisher’s logo you see on a book’s spine

Excellent interview. I greatly appreciate Sean’s work on Substack and his perspective. It cuts through all the noise and speculation that most people peddle.

Thank you for this! Great questions and I really appreciate the level of candor in the responses. I've seen a lot of gripe about the lack of editing in books these days so it was nice to see it explained by someone who actually does it. I don't tend to think there should be less books published (because as you said about genres like poetry, I think if there were fewer books published the first to be at risk would be works by BIPOC and other minority writers), instead there should be the more difficult but more lasting opposite: better pay for the people doing the editing, more editors to share the work.