Why Your Narrator Should Be a Weird Little Freak

Literature needs fewer "likeable" characters and more assholes, weirdos, buffoons, and freaks

All likeable narrators are alike; each unlikeable narrator is unlikeable in its own way.

I think Tolstoy said that? In any event, it’s a truth that I worry is forgotten in a lot of contemporary American fiction.* Over the last twenty years there has been a (often-gendered) push for “likeable characters” that has coincided with a belief that “depiction is endorsement.” This has led to a lot of characters that are frankly boring. They might be “nice” and “good” but they’re dull. And in literature being boring is the greatest sin of all.

* As someone who reads a lot of translated literature, I don’t see this problem in other countries. Most of the world embraces nasty narrators and weirdo characters.

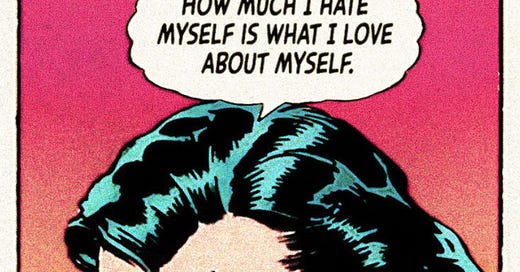

I half-jokingly tweeted something about this recently, and I thought it might be nice to kick off 2024 by encouraging authors to make their characters nasty, odd, jerky, and delusional. Especially the narrators or close third POV main characters. If we have access to a character’s thoughts, make them thoughts that are worth showing. If someone is saying your characters aren’t likeable enough, ignore them. Give us your obsessive weirdos, pompous buffoons, self-hating POS, or foolish little freaks.

The term “likeable” is confused from the start anyway. The people who advocate for likeable characters tend to mean that a character should be a Good Person™ or someone they’d want to befriend in real life. I’d argue a better way to think about likability is that you should enjoy spending time in said character’s thoughts. I probably wouldn’t want to be close friends with any of Thomas Bernhard’s miserable misanthropic narrators or Vladimir Nabokov’s many deluded narcissists. But I sure like listening to them rant.

In 2013, there was a bit of a lit controversy after an interviewer complained to Claire Messud that they “wouldn’t want to be friends with Nora, would you?” (Nora being the main character of The Woman Upstairs.) Messud was taken aback and asked the interviewer if they’d want to be friends with Saleem Sinai, Hamlet, Antigone, or countless other memorable characters from literary history: “If you’re reading to find friends, you’re in deep trouble. We read to find life, in all its possibilities. The relevant question isn’t ‘is this a potential friend for me?’ but ‘is this character alive?’”

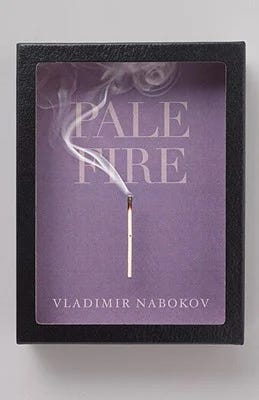

A character who is somehow at odds with society feels more alive than one who is fitting in swimmingly. Their viewpoint is unique because it is off-kilter from everyone else’s. Look at how quickly Merricat Blackwood establishes herself as a character in the opening to Shirley Jackson’s masterpiece We Have Always Lived in the Castle:

My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance. I have often thought that with any luck at all I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had. I dislike washing myself, and dogs, and noise. I like my sister Constance, and Richard Plantagenet, and Amanita phalloides, the death-cup mushroom. Everyone else in my family is dead.

A narrator doesn’t have to be a bad person to be interesting, although many excellent narrators are vile, villains, or otherwise nasty people. But they probably should indulge their obsessions, delusions, and bizarre thoughts in the way that most of us try to avoid in real life. What’s the point of literature—where access to another person’s consciousness is a key strength of the form—if our characters’ interior thoughts mirror their curated public ones? Characters can’t play it safe on the page. A prime pleasure of literature is watching characters divulge their squirm-inducing, innermost secrets to you, the reader.

It seems possible that one reason contemporary American literature has seen a decrease in the weirdness, freakiness, and nastiness of characters is the rise of “autofiction.” If you’re writing about yourself, you may be less likely to want to reveal your hidden self to the world. This is the exact wrong tactic IMHO.

Ben Lerner’s best novel is easily Leaving the Atocha Station, and it’s precisely because the narrator kinda sucks. He’s pompous and phony and a bit of a shit. The Lerner narrator may not be “likeable” in that you’d want to be his best friend, but he’s very likeable in the sense of being enjoyable to read. The same holds for other classics of autofiction, like Rachel Cusk’s weird and detached narrator in Outline or Teju Cole’s asshole (and worse) narrator in Open City or Tove Ditlevsen’s messy character in The Copenhagen Trilogy. Etc. If you’re using autofiction to prove that you, via a fictional stand-in, are a good and honest person whose flaws can only ever be sympathetic and whose mistakes easily excused, well, your fiction will likely be pretty boring.

Even in comedic forms, like satire, a lot of authors seem to play it safe these days. Perhaps they think they must “punch up” at their main targets and leave their heroes unscathed. This is a topic for another, longer post but I’d argue satire never quite works unless the eye is turned back on itself. The satiric eye should see, and scathe, everyone.

I agree with Messud that you shouldn’t look to literature for friends. Yet it is is also true that even your friends are freaks, losers, and jerks in various ways. Aren’t we all little weirdos at heart? Fiction is exactly the place to expose those hidden parts. So in 2024, make a resolution to show the reader your character’s real interiors. Warts most of all.

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.”

Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

This point can’t be made often enough for me.

Yes yes yes. Perfectly unimpeachable narrators are yawnsville in memoir too. Self-incrimination is incredibly compelling (and probably crucial) in that genre. Thanks for a great post!