Write for Your Best Readers Instead of Your Worst Readers

A little plea to stop judging art by what the dullest take away

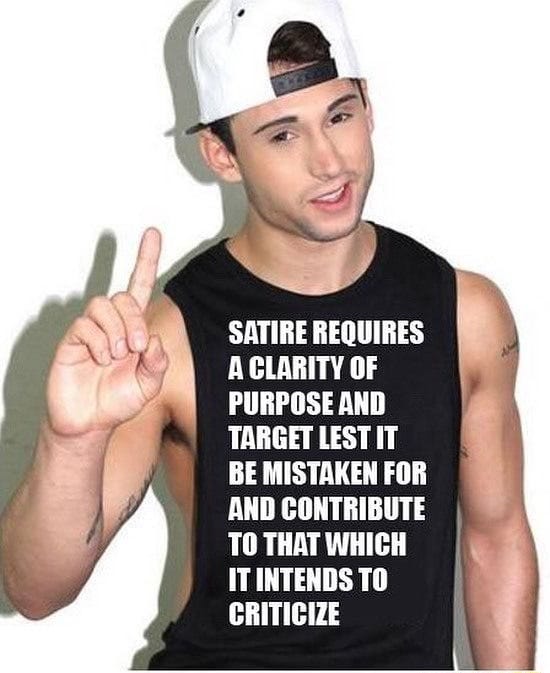

The internet is full of dumb memes people think are smart, but a particularly irritating one is satire guy. If you’ve wasted any time on social media, you’ve seen him:

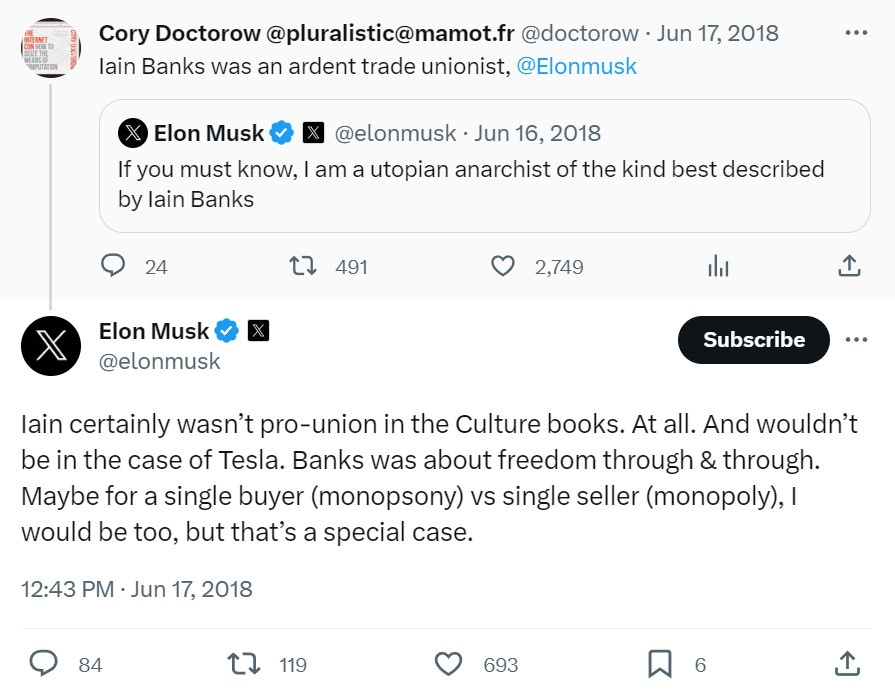

Satire guy popped into my head yesterday during a discussion of the alleged “failed satire” of The Boys, a show that some dumb right wing viewers didn’t understand was critiquing them. I don’t have any particular feeling about The Boys, but the idea that satire has failed if some people don’t get it is a standard nothing can meet. There are lots of stupid people in the world. Conservatives and even fascists routinely cite George Orwell, a man who literally went to Spain to fight fascists alongside socialist and anarchist brigades. Capitalist plutocrats like Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk claim the legacy of Iain Banks’s anti-capitalist novels. Recently, a post made the rounds with a comic reader shocked Judge Dredd was a satire.

So on and so forth.

A famous anecdote about Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” is that outraged New Yorker readers wrote in to cancel their subscriptions. To me, the more telling anecdote is that Jackson herself was deluged with letters: “People at first were not so much concerned with what the story meant; what they wanted to know was where these lotteries were held, and whether they could go there and watch.”

This view of satire—that fails if some dullard doesn’t understand it—dovetails into the popular idea of art as moral instruction in which the greatest failure a work of art can do is confuse someone about the intended message. This literature as Goofus and Gallant comic strip view of literature says it’s the fault of the artist when someone fails to understand that depiction isn’t endorsement or that fictional characters may say things the author doesn’t believe. These types—common across the political spectrum—claim art must explicitly rebut any “bad” thing it depicts. If a villain says something bigoted, a henchman needs to pipe up and say, “Hey, that’s not nice and here’s why!” If a character does something bad, the plot must punish them so no one gets confused. To such readers, it seems the only safe way write a novel is for the author to footnote every single sentence with either “I think this is good!” or “I think this is bad!”

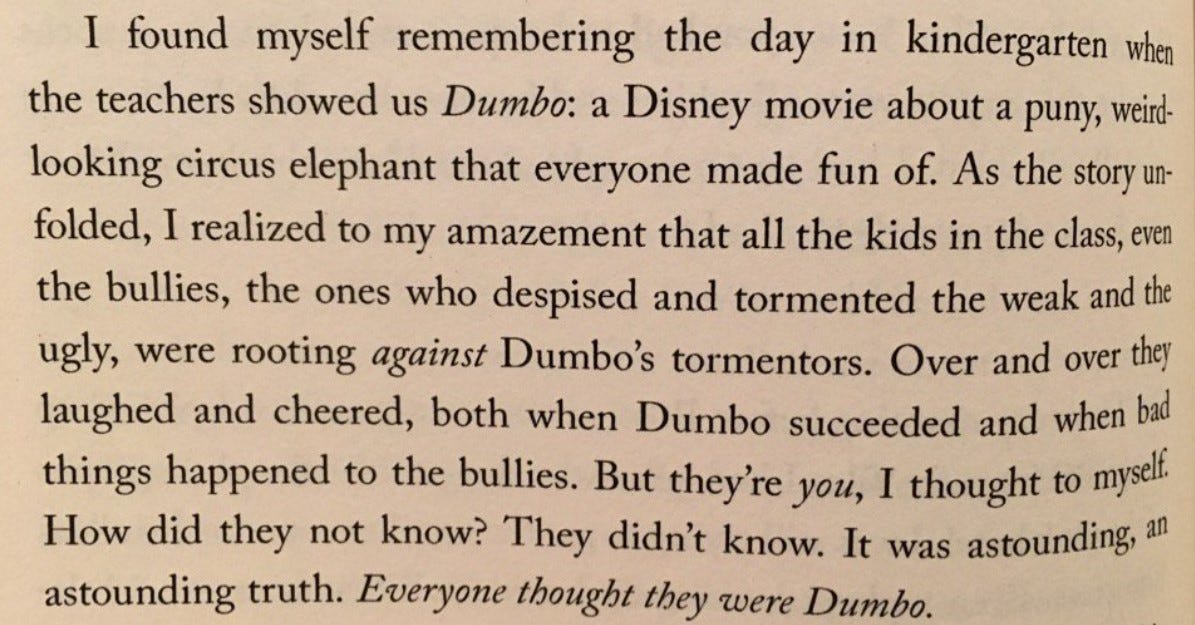

Even that wouldn’t be enough though. People take whatever they want from art. Conservative Paul Ryan listens to overtly leftwing bands like Rage Against the Machine. This isn’t because Paul Ryan doesn’t understand RATM’s lyrics target people like him. He just doesn’t care: “I hate the lyrics, but I like the sound.” Even if Elon Musk gained media literacy, he’d still likely read anti-capitalist science fiction and take nothing away except “spaceships are cool!” Even the biggest bullies will find a way to consider themselves the bullied. Etc.

Art isn’t osmosis. There’s no way to force everyone to absorb your intended message. It’s simply not how things work. But beyond the impossibility of that task, we should think about what gets lost when we focus on appeasing dullards. If we are so concerned about what might confuse our worst readers, what is left for our best readers? If all art must be blunt, what about readers who desire subtlety? If our stories are simplistic, what about people who enjoy complexity? Do we really want all our art to be flat, formulaic, and dulled of any edge? Focusing on not confusing our worst readers ensures that we bore our best ones.

So I say ignore your worst readers. There’s simply no way to appease, instruct, or impress them anyway. The greatest works of literature are still riddled with one-star Goodreads reviews. If you set the bar high you may fail, but you’re still more likely to produce something interesting and unique. If you set the bar low, you can only end up on the ground.

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.”

Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

I also think it's okay -- depending on the work, sometimes even preferable -- for the reader not to know where the author stands on their own themes or characters... or for the author in fact not to know. I think of that David Lynch quote about how, if he could explain his movies in words, he wouldn't have to make them as films. Even though we're using words to construct our stories, if we were able to reduce those stories to a pat explanation, we wouldn't need to dramatize them (or whatever other literary strategy we're using to bring them to life). This is also often the way that imperfect humans with uninspected biases and bigotries can create works that seem a lot wiser than those problematic creators.

Fuck yeah.