The Grotesque Sublime

Combining the revolting with the astonishing in horror fiction

For the last few weeks, I’ve been teaching a unit on horror fiction with a focus on horror effects. One of the things I love about horror fiction (and it’s ancestor Gothic fiction) is the how the theory around the genre focuses on the emotional and psychological effects the words can conjure in readers. This is something creative writing classes rarely seem to talk about. Perhaps strangely, since what is the point of art if not to create emotional effects in the reader? But then most other genres are defined by elements like settings, tropes, and plots while horror is defined by, well, what horrifies. It is defined by effect.

The Spooky Spectrum

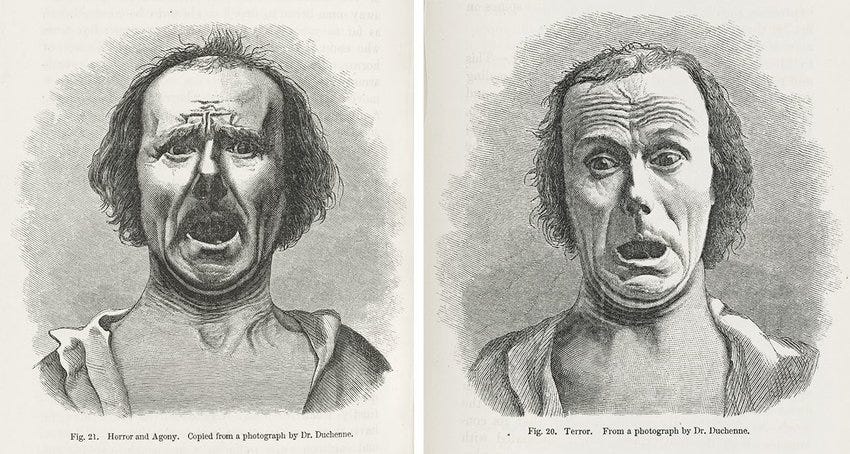

In horror and Gothic studies, the classic division is between horror and terror. In everyday language, these are synonyms. But in horror fiction they stand for two almost opposite effects. The distinction originates with the Gothic writer Ann Radcliffe and basically breaks down this way:

HORROR is defined by clarity. It is a feeling of revulsion at directly seeing the monstrous. The beast biting off someone’s head. The blood on the walls. The putrid scent of decaying flesh. All that fun, vile stuff.

TERROR is defined in contrast by obscurity. It is the footsteps of a beast outside your door. The shadowy figure lurking in the dark outside your window. The feeling that everything around you is just off in some imperceptible way.

While these might seem similar, Radcliffe argues “Terror and Horror are so far opposite, that the first expands the soul and awakens the faculties to a high degree of life; the other contracts, freezes and nearly annihilates them.” Think about real life. If you stumble upon bloody roadkill walking down the street, you probably feel a deadening sense of revulsion. If you wake up late at night to hear strange sounds outside your door, you are pumped with adrenaline and suddenly feeling very alive (if terrified). Something similar happens when reading horror fiction, at least according to Radcliffe.

In Danse Macabre, Stephen King expands this binary to more of a spectrum by adding in the idea of the “the gross out”:

The three types of terror: The Gross-out: the sight of a severed head tumbling down a flight of stairs, it's when the lights go out and something green and slimy splatters against your arm. The Horror: the unnatural, spiders the size of bears, the dead waking up and walking around, it's when the lights go out and something with claws grabs you by the arm. And the last and worse one: Terror, when you come home and notice everything you own had been taken away and replaced by an exact substitute. It's when the lights go out and you feel something behind you, you hear it, you feel its breath against your ear, but when you turn around, there's nothing there...

King’s last example feels a bit more like the concept of “the uncanny” to me than pure terror, although the uncanny and terror overlap in many ways. Still, the gross out seems a useful addition in our age of “torture porn” films and “splatterpunk” fiction. The explicitness of gore in much of modern horror is far beyond what it was in Radcliffe’s day. But you can probably easily see the spectrum from the most overt and revolting gross-out effects to the most obscure and mysterious terror effects. The more over the image is, the more it revolts. The more obscure it is, the more it enlivens with a sense of mystery and dread.

For Radcliffe, the latter is what lead us to experience the sublime.

The Grotesque Versus The Sublime

“As a means of contrast with the sublime, the grotesque is, in our view, the richest source that nature can offer.” — Victor Hugo

Another way to think of these effects is that they exist on a scale of the grotesque to the sublime. The grotesque here meaning the exaggerated and the monstrous that produces a sense of revulsion (if also fascination). The grotesque may be repellent, but it is typically contained and understandable. The sublime on the other hand is that which is so vast and impossible to comprehend that it produces a strange feeling of both awe and terror.

(I’m simplifying of course. These terms all have lots of complex and sometimes contradictory uses in different time periods and fields.)

It makes sense that terror, with it’s indirectness, would lead to the sublime. The classic examples of the sublime are the great dark and violent forces of nature. Hurricanes, earthquakes, giant waves, and so on. At a distance, these forces overwhelm you with their violence and vastness. You feel the sublime. However, you probably only feel that sublime when you are in fact at a distance. When you yourself are being knocked over by waves or thrown about by a tornado, well, you have other things to worry about. Similarly, you feel the sublime via the obscurity of terror—the creepy noises outside your door—because of the distance. When the beast bursts through the door and bites off your arm, you aren’t focused on aesthetic bliss.

Summoning The Grotesque Sublime

So on the one hand you have the grotesque and the clear. On the other hand you have the sublime and the obscure. Because I like to be contrary, I of course want to think about when these binaries can be collapsed or combined. When can horrifying be terror? When can the grotesque be sublime? Is there a way to combine clarity and incomprehension?

While terror and horror, and grotesque and sublime, might be useful to think about as opposite poles there are clearly times they touch. It’s hard to think of a film more invested in terror over horror than The Shining. There are only a few moments of clear and overt horror in the film like the bloody-headed party guest or the flashes of skeletons. Most of it’s dread is the lingering shots or distant but not directly violent images like the twins in the hallway. And yet isn’t it’s most iconic image one that combines the gross-out with the sublime?

Here we have the grotesque image of buckets of blood—completely clear—yet the scene also imparts the sense of vastness and awe that leads to the sublime. The viewer is not revolted by this image, or at least not only revolted. They are also in awe. It’s blood, yes, but more blood than we can easily grasp. That feels like the first key to combining the grotesque and the sublime: scale.

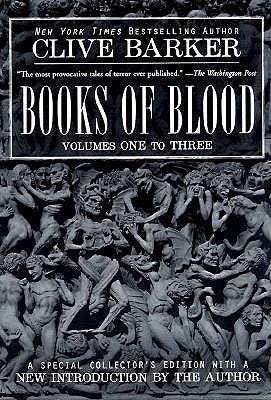

In literature, the first grotesque sublime image that comes to mind is from Clive Barker’s classic weird horror story “In the Hills, the Cities.” In that story, a couple vacationing in Yugoslavia stumble upon a bizarre ritual in which townspeople fasten themselves together with into gigantic people-skyscrapers that fight each other. Some errors in the bindings cause one of the people-skyscrapers to collapse, killing many thousands. The other people-skyscraper goes collectively insane. It is a bizarre and impossible idea, and one that I think squarely hits both the grotesque and the sublime.

(We might also add in cosmic horror images here, although in Lovecraftian fiction the vast and horrifying monsters are typically purposefully ill-defined. We know they have tentacles, maybe, but they are supposed to be impossible to grasp and mostly described with abstract adjectives: non-Euclidean, stygian, cyclopean, etc. The fact that Cthulhu has been reduced in the public imagination to simply a green octopus-head guy has I think deadened his cosmic horror effect.)

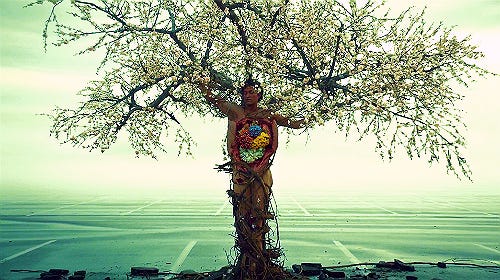

But scale doesn’t seem like an absolute requirement of the grotesque sublime. Hannibal, one of the best horror shows ever, is filled with images of the grotesque sublime. In the show, the serial killers turn their killings into essentially art projects. Sometimes culinary art and sometimes visual art, but the images of the show combine a deep revulsion with a kind of spirituality or aesthetic awe.

David Lynch is a director whose works often traffic in the grotesque sublime. And of course in both Lynch and Hannibal the effect is not merely the image itself, but also the mysterious beauty of the cinematography, music, and colors. In literature, the moments of the grotesque sublime are likewise generated by a beauty and mystery to the language and the syntax. Brian Evenson’s work, for example, combines elliptical and poetic prose with grotesque and macabre images. One thing Evenson has said is that he tends “to focus on the terror that comes before the apocalyptic moment or, sometimes, on the aftermath: what it’s like to pick up the pieces after the disaster.” his might be the third feature of the grotesque sublime: a certain distance from the violence.

The grotesque sublime is normally not attacking or threatening the characters. At least in that moment. The grotesque sublime image instead stands in as a kind of omen or monument to the darkness lurking within or behind. Here I’m borrowing an idea from Sean T. Collins in his excellent essay “All Hail the Monumental Horror-Image.” Collins talks about how horror films often have shots of horrifying and largely still images—sometimes actual statues, as in The Exorcist, but other times apparitions or objects that should not be—that imply a lurking evil.

Both types of monumental horror-image are rarely if ever directly violent. Often they don’t even imply an imminent threat. The monumental horror-image does what “here be monsters” did in maps centuries ago — they mark the border where life as we know it gives way to the terrifying unknown.

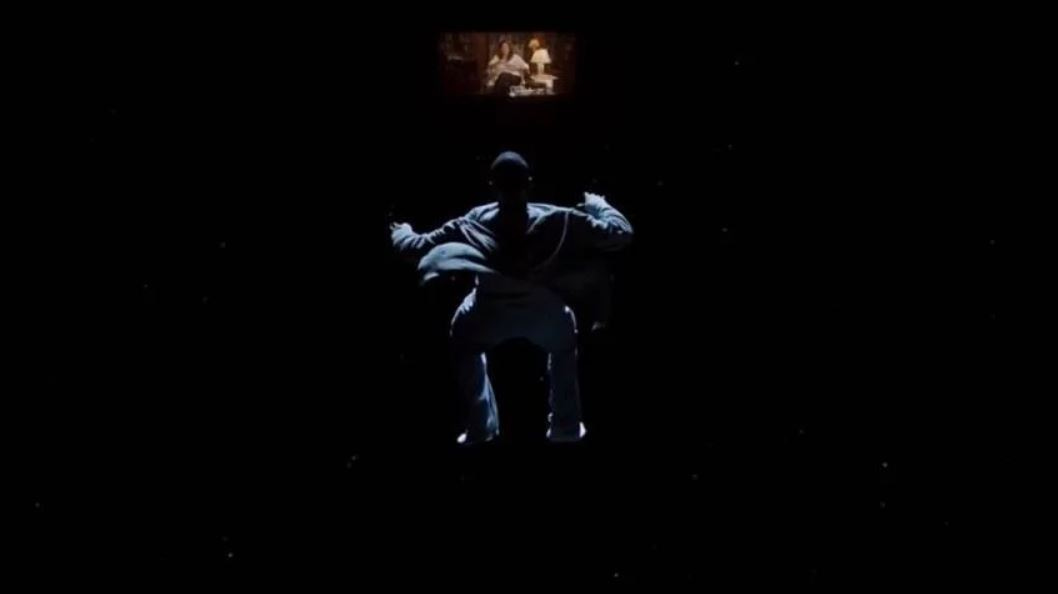

(Is it possible for this kind of monumental horror-image to also be a threat to the character? Something like “the sunken place” in Get Out might qualify.)

Monumental horror-images don’t have to be grotesque of course, though many are. Collins was focused on film in that essay, but I think similar effects can be put on the page. Think of the topiary animals in the novel version of The Shining or again Barker’s people-skyscrapers.

To tie this back to initial horror / terror distinction, the grotesque sublime manages to combine the clarity of horror with the obscurity of terror. That is to say the images themselves are clear but their meaning is obscure. The police and FBI agents who see the seal killer art pieces in Hannibal do not comprehend them. Danny Torrance, and the viewer, know that blood is pouring out of an elevator. But we do cannot fully grasp what that means.

We know only that it is grotesque portal to the sublime abyss. We cannot comprehend the it, yet once we have seen it we can never unsee.

In personal news, Esquire named The Body Scout one of the 50 best science fiction books of all time (!!). And my Virginia Festival of the Book panel with Ryka Aoki and Micaiah Johnson is online if you missed it.

As always, If you like this newsletter, please consider subscribing or checking out my recently released science fiction novel The Body Scout, which The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent” and Boing Boing declared “a modern cyberpunk masterpiece.”

Of all the horror things, I strangely only enjoy the gothic. It’s just a much subtler, seeping, creepingly romantic, and hauntingly beautiful thing. Never does it dip into the grotesque, nor the terror, and yet it is even darker than those rivals for its philosophical angst. We need to bring gothic back!

Really insightful! I wonder where on the continuum you might put weird lit and film - which also seem to fuse the grotesque and sublime. I'm thinking specifically of China Mieville, whose wonderful city New Crobuzon is set astride an enormous still-decaying carcass of some huge, ancient, fantastical creature. A movie which seems to fuse these elements (also using scale, setting, and psychology) is Dark City which uses a front of noir, but gradually transforms into something much more chilling and horrifying as we progress through its plot. Lastly, I'm going to plug a couple books that really pull off some of this by an author team who can be found @ismaebooks - Things They Buried and They Eat Their Own. Both books are wonderful genre mashups, but the first really sinks into this topic quite a bit. They won an Ippy award for TTB and I think you'd really enjoy it. Thanks!