Style Is More than Sentences

In defense of style and the infinite possibilities of storytelling

Style has become a dirty word in many literary circles. To care about style is “pretentious” and “snobbish” and anyway the goal of fiction is to have the prose “get out of the way of the story.” And what is story except a procession of plot points? I’ve always found this view to be, fairly literally, nonsense. A novel is made of prose. How could the prose get out of the way of itself? It’s like saying the paint should get out of the way of the painting. The way a story is written is intricately tied to everything else: the tone, the plot, the characters, etc. The same “story” could be told in infinite ways to different effects depending on the style of the prose, in the same way a portrait can be painted in infinite ways depending on the style of the painter.

Style is the water that you swim through as a reader. The book’s style sets the tone, atmosphere, and general vibe of the work. But style is more than that. Style is not just a matter of word choice or grammar. Style is composed of all the choices an author makes. What is the voice of the narrator? What is the structure? The form? Will the story be told with digressions and asides or stick only to bare-bones action? Will chapters be single long scenes or jumbled fragments? If there are unreal elements in the book, will they be described in a surrealist or fabulist or epic fantasy or gothic style? In this way, saying that style “gets in the way of story” is also a nonsensical statement. The story itself will be different depending on the style it is told.

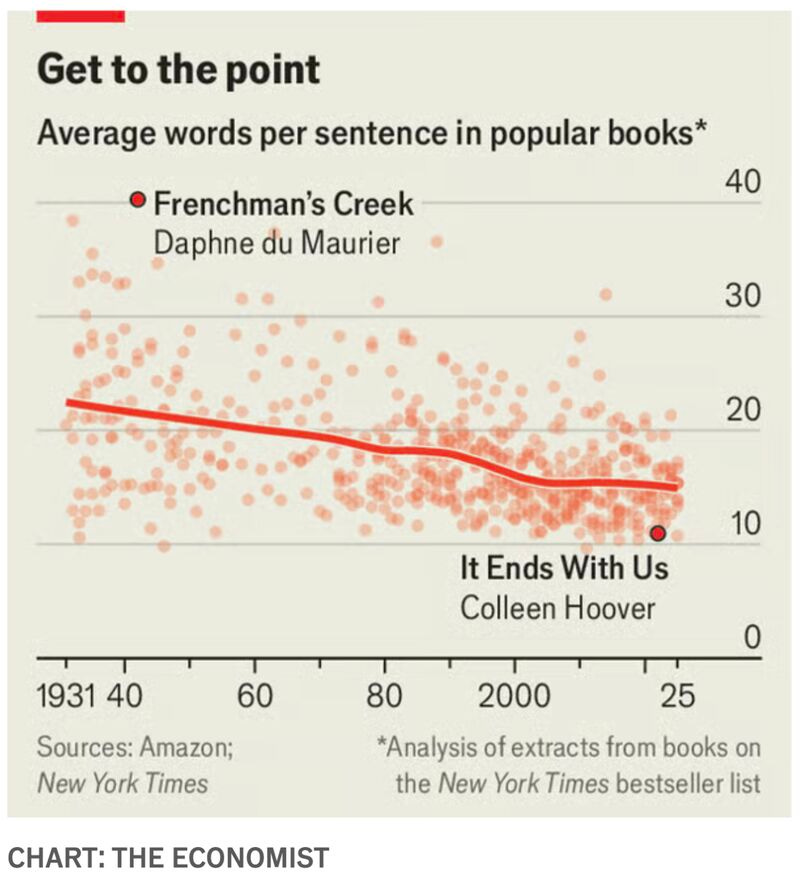

Of course, I know what people mean. They mean that there is a familiar and narrow range of stylistic choices that they enjoy reading. They consider this a non-style in the way that people tend to think everyone else speaks in a dialect and they just speak “normally.” But the popular style of prose is a style, and one that changes as tastes change. The style of popular commercial fiction today is different from what it was twenty-five or fifty years ago, even down to the length of sentences. What is “invisible prose that doesn’t get in the way of the story” today may be tomorrow’s “pretentious and unreadable book.”

To each their own. It takes all kinds. Yada yada. Read what you like. But I wanted to give a little defense of style, in its infinite forms, and especially to rebut the idea that style is merely a matter of “pretty sentences.”

I’ve had a post titled “Style Is More than Sentences” in my drafts for a while, but I thought of this topic again when I read Devon Halliday’s article “My Literary Fiction Is More Literary Than Yours.” This is a good article. I recommend it, especially for writers who are in the querying stage. I’ve seen several authors restack the article surprised to learn about the term “upmarket.” (“Upmarket” basically means commercial fiction that’s well-written, or more specifically the kind of books you pitch to big book clubs like Jenna, Oprah, and Reese.) Halliday breaks down the way editors and agents think about book categories, and usefully distinguishes style from content. Content here is basically genre. Style is a spectrum of “commercial → upmarket → literary.”

This spectrum is meant to indicate something about the writing of the book, whereas genre is meant to indicate something about the content. So by this system, every book has both a genre (e.g. thriller) and a location on the spectrum (e.g. upmarket). One does not determine the other2; they are two separate methods of evaluating and labeling a book for the marketplace.

This seems exactly right to me. From a publisher’s point of view, terms like “literary,” “upmarket,” and “commercial” are as much about the style of the book as the content. A novel about a detective solving a crime could be written in a lush and poetic style (such as The Taiga Syndrome by Cristina Rivera Garza) or a philosophical and postmodern style (such as The New York Trilogy by Paul Auster), and thus be “literary,” or it could be written in simple prose with short chapters, breezy pacing, and adherence to formula and be a Dan Brown or James Patterson bestseller. If it is commercial in form and content but somewhat more literary in execution, it is “upmarket” and pitched to book clubs.

Where I disagree is when Halliday tries to find a “neutral” definition of literary vs. commercial writing:

Literary writers, good and bad, want you to notice their sentences. We can argue about how much fun it is to read Henry James’s neverending sentences full of nested clauses, but we will agree regardless that we are called upon to notice the sentences. […]

And commercial writers, good and bad, want you to stay focused on the story, without getting distracted by the sentences. There can be really good sentences in commercial fiction, but they’re not the kind that you’re meant to puzzle over and read out loud to your friends.

Upmarket, therefore, is a blend: the reader’s focus is shared, to varying degrees, between the sentences as sentences and the sentences as story material. Elena Ferrante is, I think, on the literary end of upmarket: she makes unusual and noteworthy choices in many of her sentences, but when I read the Neapolitan Novels, I can’t remember ever lingering for long on a particular sentence construction.

Halliday also links “purple prose” to literary fiction and says commercial fiction writers “do put care into every word they write.” Many comments on the article, and many restacks I saw, seem to believe that style is just pretentious sentences getting in the way of the real point of fiction: the procession of plot points.

It is quite useful to think of “literary” style as separate from genre. Your Toni Morrisons and Don DeLillos of the world are quite literary in style, but so are your Ursula K. Le Guins, Raymond Chandlers, Octavia Butlers, and Shirley Jacksons. Throughout this article I will be using “literary” in this sense of stylish and artistic writing in whatever genre. (The fact that “literary fiction” is also used to mean a certain genre, or set of genres, of fiction is a problem for another article.)

But, the attempt at a neutral definition of literary prose ends up sounding insulting to literary authors while also being, in my view, inaccurate. It sounds as if literary authors are just in love with their own pretty sentences and aren’t thinking about story, theme, character, and everything else that makes up a story. That all that literary stylists care about is “pretty sentences” and that there are no differences between literary works—again, in any genre—and commercial work other than the use of a thesaurus. I think the differences are much larger than sentences, touching everything from plot to structure to character. Ferrante’s novels are very literary, in my view, not because she writes beautiful sentences one can linger on—although I think she does—but because of the form, themes, and overall style of her work.

Don’t get me wrong. There are some literary authors who care mostly about pretty sentences. Who write dull novels that seem to be nothing but a collection of random clever thoughts strung together with the barest threads of plot and character do exist. Though if we’re cherry-picking the worst examples of the category, then I might point out that many commercial fiction authors obviously don’t “put care into every word they write” since they often…. don’t even write every word. Ghostwriters penning brand-name author books, commercial fiction factories, and collaborations with editors and agents tailoring the books to “TikTok hashtags” are common in the commercial fiction world. Often, there is less careful attention to the word choices and more—this is a real anecdote from a ghostwriter—“Hey, so the Hollywood production company that bought the film rights thinks they’ll sell more toys if the hero has a cool sword. We need a rewrite with a cool sword pronto.”

If you think I’m being unfair to commercial fiction authors, well, as the old Don Draper meme goes, that’s what the money is for. They can take a little snark in exchange for seven-figure advances and massive marketing budgets. But I will also point out that the books I’m referencing are the cream of the crop by the standard of the category aka sales. Case in point: the most successful commercial author alive is likely James Patterson, who famously leaves the writing to an army of ghostwriters and co-writers while publishing up to several dozen books a year.

Of course, many commercial authors do write their own books. Some of them are very good. Yet I’d also disagree that commercial fiction isn’t prone to purple prose or that fans of commercial books don’t share sentences. We know they do because we can see the likes on Goodreads and the screenshots on social media. Commercial fiction is often filled with zippy dialogue and florid metaphors. There are Tuesdays with Morrie-esque books overflowing with aphoristic life lessons. I’ve written before about how the most in-your-face sentences I’ve ever read were in bestselling commercial fiction books:

“My skin buzzes, like my blood is made of iron fillings and his eyes are magnets sweeping over them.”

“The monsters almost seemed to blend and shift together, one enormous dark force of howling, miasmic hatred as thick as the air—which seemed to hold in the heat and the humidity, like a merchant hoarding fine rugs.”

“Her expression is one Luca has never seen before, and he fears it might be permanent. It’s as if seven fisherman have cast their hooks into her from different directions and they’re all pulling at once. One from the eyebrow, one from the lip, another at the nose, one from the cheek.”

“The flight to Atlanta (on a private jet) and the drive farther south to Golden (in a chauffeur-driven Lincoln Town Car) had transported him to a world of warmth, abloom in myriad shades of green, yellow, lavender, and pink.”

These are not cherry-picked sentences from obscure novelists. The first three are extremely popular authors in different genres (Emily Henry, Brandon Sanderson, and Jeanine Cummings, respectively) whose books contain many sentences along those lines. The last example is taken from the first paragraph of chapter one of the buzziest commercial fiction book on the market: a self-published novel called Theo of Golden by Allen Levi that is currently—I hear—in a Big 5 bidding war in the multiple millions. Clearly, sentences abloom in myriad shades of purple aren’t a hindrance to commercial success.

On the flip side, many literary authors do not have eye-catching sentences per se. Some do, some don’t. From my vantage, literary-minded authors (in any genre) use prose as a medium akin to how painters use paint. Prose is shaped in different ways to create different effects, to craft individual styles, and to push the boundaries of the art form in new directions. That doesn’t mean they’re all good or even original. Many are bad and generic. But they are trying things outside of the standard narrow range of popular fiction.

Individual commercial fiction sentences are often screaming for attention. But the overall prose tends to conform to a narrow stylistic range. The sentences, yes, but also the structures, POVs, forms, and all the rest. As an obvious example, modern commercial fiction books tend to have short chapters. Choosing short chapters over long chapters or no chapters or a series of fragments is a stylistic choice. This is fine, of course. Many readers want to know exactly what they are getting and enjoy slight variations on the same story. A quick scroll through the current bestsellers shows they’re almost all sequels in long-running series. “The 15th book in the Isaac Bell series.” “The 23rd book in the Black Dagger Brotherhood series.” “The 61st book of the In Death series.”

Again, that’s fine. People should read what they want. Obviously, we live in a culture where people enjoy returning to the same universes and characters. Where Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, and a handful of other properties seem destined to be rebooted endlessly. Where the MCU became the most successful film series of all time by pioneering a bland style that allows directors, writers, and actors to be swapped in and out without affecting box office performance.

But, the storytelling possibilities of fiction are limitless. So, I am quite thankful there are still many authors who will attempt to do something at least a little different.

Again, I have to stress that style is a lot more than sentences. The acceptable range of choices for commercial fiction is quite narrow. A book that is written as a series of genre-hopping nested narratives (like Cloud Atlas) or a long monologue rant (like Woodcutters) or a catalog of fictional settings (like Invisible Cities) or in fragments (like Speedboat) or that contains a novel within the novel (Erasure) or that is told entirely in digressions during a single moment (like The Mezzanine) or—one could go on forever—any other unusual structure is unlikely to be given commercial fiction treatment. Those stories would be literary, in this sense, regardless of the sentences used.

All of these are elements of an author’s style. The digressions of Baker or the metafictional commentary of Everett or the recursive rants of Bernhard. Such choices are as much a part of a style as word choice and syntax.

Literary-minded readers are often drawn to an author’s style and will follow an author across subject matter. An author like Kazuo Ishiguro has written books of quiet realism, surrealism, fantasy, and science fiction, among other genres. His fans are happy to follow him wherever he goes. (Obviously, many are readers of both commercial and literary work. There’s nothing wrong with seeking different pleasures at different times.)

The style that attracts a literary reader is not necessarily about dense or complex or challenging sentences. Some styles go down like a cool glass of water. It is more about how the author builds an entire style from all the infinites choices. Since I brought up Ishiguro, here the opening to Never Let Me Go:

My name is Kathy H. I'm thirty-one years old, and I've been a carer now for over eleven years. That sounds long enough, I know, but actually they want me to go on for another eight months, until the end of this year. That'll make it almost exactly twelve years. Now I know my being a carer so long isn't necessarily because they think I'm fantastic at what I do. There are some really good carers who've been told to stop after just two or three years. And I can think of one carer at least who went on for all of fourteen years despite being a complete waste of space. So I'm not trying to boast.

It goes on this way for, well, the whole book. The prose style is as clean and clear as any commercial fiction prose—in fact, more so, as the commercial authors are prone to inserting flashy purple lines throughout. This restrained style pairs perfectly with his bottled-up narrators and their repressed emotions. It isn’t merely about the sentences, but the total effect of the prose in the context of the story.

Ishiguro’s style might be called minimalist, but is different from other minimalist styles. Compare to the Carver story “Popular Mechanics” (this is the ending):

Don't, she said. You're hurting the baby, she said.

I'm not hurting the baby, he said.

The kitchen window gave no light. In the near-dark he worked on her fisted fingers with one hand and with the other hand he gripped the screaming baby up under an arm near the shoulder.

She felt her fingers being forced open.

She felt the baby going from her.

No! she screamed just as her hands came loose.

She would have it, this baby. She grabbed for the baby's other arm. She caught the baby around the wrist and leaned back.

But he would not let go. He felt the baby slipping out of his hands and he pulled back very hard.

In this manner, the issue was decided.

Here, the simple sentences are surrounded by white space and narrated in essentially a third person objective POV, stretching out the scene and forcing the reader to focus on every mechanical step and let their imaginations fill in the horrible empty space.

Choices of POV and paragraph breaks affect style just as much as the sentences. Indeed, a useful exercise for beginning writers is to take a scene and remove all the paragraph breaks. Then try a half-dozen variations of the scene without changing a single word, but adding paragraph breaks at different points. How does the scene read as one long chunk? Or a ton of airy short paragraphs? Or with a key line given its own paragraph between larger ones? Which variation works best for the story you are telling?

This strikes me as a key feature of literary writing, at least good literary writing: the style works in conjunction with the other elements to form a unified whole. (If the work is disjointed, that is also by intent and crafted with intention for different effects.) It isn’t that the sentences get in the way of the story or overshadow the characters. The prose shapes the story, deepens the characters, and furthers the themes. Or you could equally say the story, characters, and themes shape the style. It should all be working together.

To reduce literary style to “sentences,” as so many do, is akin to reducing the style of painters to “brushstrokes.” Brushstrokes matter, sure. Some styles, say the thick swirls of Van Gogh or the pointillism of Seurat, are very brushstroke-forward (I’m sure painters have a better term here). But, just as obviously color, composition, pattern, light, and many other aspects of a painting all work together to form an artist’s style.

The same is true of fiction. Even if we could extract story from style—which we really can’t—the use of paragraphs, form, and structure are just as tied into the prose as sentences. The difference between a story told in chronological chapters vs. one that skips around in time. Is the tone comic or somber? Is there a foreboding or lighthearted atmosphere? All of these kinds of questions add up to the overall style of a good book in mutual reinforcement.

Here are two famous passages about the same subject, the horrors of war, from two very different stylists: Hemingway and McCarthy. I know Hemingway has fallen out of fashion, in part because his style was imitated to death. I don’t love all of Hemingway, but one Hemingway book I always think of is In Our Time. That book collects short stories, many about soldiers having returned from WWI. Between the stories proper are interstitial scenes of the war written in a sparse, stone-faced style that create (at least for me) a very powerful effect. Here’s one [italics in the original]:

They shot the six cabinet ministers at half-past six in the morning against the wall of a hospital. There were pools of water in the courtyard. There were wet dead leaves on the paving of the courtyard. It rained hard. All the shutters of the hospital were nailed shut. One of the ministers was sick with typhoid. Two soldiers carried him downstairs and out into the rain. They tried to hold him up against the wall but he sat down in a puddle of water. The other five stood very quietly against the wall. Finally the officer told the soldiers it was no good trying to make him stand up. When they fired the first volley he was sitting down in the water with his head on his knees.

Here, the short and unadorned sentences, told at a cold remove, emphasize the deadening effects of war and the characters’ repression of their trauma. Contrast that with a famous scene from Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian, where the loopy and chaotic sentences showcase instead the chaos of war as well as the mythic sense of the eternal nature of struggle:

Now driving in a wild frieze of headlong horses with eyes walled and teeth cropped and naked riders with clusters of arrows clenched in their jaws and their shields winking in the dust and up the far side of the ruined ranks in a piping of boneflutes and dropping down off the sides of their mounts with one heel hung in the withers strap and their short bows flexing beneath the outstretched necks of the ponies until they had circled the company and cut their ranks in two and then rising up again like funhouse figures, some with nightmare faces painted on their breasts, riding down the unhorsed Saxons and spearing and clubbing them and leaping from their mounts with knives and running about on the ground with a peculiar bandylegged trot like creatures driven to alien forms of locomotion and stripping the clothes from the dead and seizing them up by the hair and passing their blades about the skulls of the living and the dead alike and snatching aloft the the bloody wigs and hacking and chopping at the naked bodies, ripping off limbs, heads, gutting the strange white torsos and holding up great handfuls of viscera, genitals, some of the savages so slathered up with gore they might have rolled in it like dogs and some who fell upon the dying and sodomized them with loud cries to their fellows.

Now, you can love or hate both of these passages. Either way, you should be able to see the varying effects of different styles even when dealing with the same subject matter.

Style, in the larger sense, beyond just sentences, is integral to understanding content too. That is to say, it is fundamental to genre. What would hardboiled detective fiction be without hardboiled prose? Or a fairy tale without the simple language and storyteller voice? Or Gothic fiction without the moody style that creates the chilling atmosphere? It is hard for me to mention Gothic fiction without quoting Shirley Jackson’s sublime opening of The Haunting of Hill House:

No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.

These are beautiful sentences, yes, with lovely alliteration and assonance. But they also are strange sentences that guide the reader into the strangeness of Hill House, whose architecture is as bizarre as the grammar.

Style can sometimes be the key difference between genres. What separates urban fantasy from the magical realism of writers like García Márquez is largely a question of style. Magical realism tends to make the mundane seem magical and the magical seem mundane, blurring them together, as evidenced in the opening of “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings”:

On the third day of rain they had killed so many crabs inside the house that Pelayo had to cross his drenched courtyard and throw them into the sea, because the newborn child had a temperature all night and they thought it was due to the stench. The world had been sad since Tuesday. Sea and sky were a single ash-gray thing and the sands of the beach, which on March nights glimmered like powdered light, had become a stew of mud and rotten shellfish. The light was so weak at noon that when Pelayo was coming back to the house after throwing away the crabs, it was hard for him to see what it was that was moving and groaning in the rear of the courtyard. He had to go very close to see that it was an old man, a very old man, lying face down in the mud, who, in spite of his tremendous efforts, couldn't get up, impeded by his enormous wings.

Anyway, one could go on with examples forever because the stylistic diversity of fiction is infinite. That is also why it is worth celebrating authors who are thinking about the possibilities of prose. Who try different styles and push the form in search of deeper truths and new ways of seeing the world. They may often fail. The familiar is always more likely to succeed in the commercial marketplace. Still, it is good to have artists who are trying.

I realize that what I’m saying is, in many ways, quite basic. Sometimes the basic can be forgotten, even in literary circles. There is indeed sometimes a “cult of the sentence” mindset among literary writers and larger questions of story, theme, and so on can be forgotten. In the work of emerging writers, there can be a tendency to cram as many beautiful sentences as they can into the text willy-nilly without thinking of larger effects. Sometimes, that can be the whole vibe. Often, it is a matter of writers not thinking about the work as a whole. As writers mature, they tend to realize it is far more effective to deploy attention-grabbing sentences at strategic moments to direct the reader’s attention to the most pivotal or powerful moments. Cool sentences mean little if they don’t work together as part of the larger project.

This is really the gist of “kill your darlings.” You have to learn to cut the things that don’t work in the context of the story, even if they sound cool on their own.

If you’re an author more inclined toward a literary style than a commercial one, or simply trying to craft a style regardless of labels, then I would highly encourage you to think of style as far more than “sentences.” What is the best pacing of paragraphs and chapters? What story opportunities are opened (or closed) by the POV you choose? How can the structure inform your themes and vice versa? All of this shapes your style. And the possibilities of style, of storytelling, are limitless.

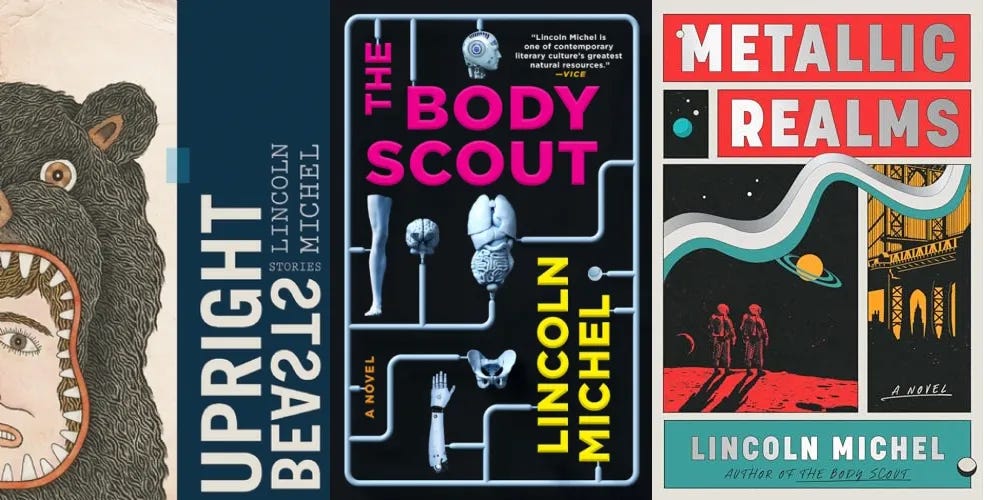

My new novel Metallic Realms is out in stores! Reviews have called the book “brilliant” (Esquire), “riveting” (Publishers Weekly), “hilariously clever” (Elle), “a total blast” (Chicago Tribune), “unrelentingly smart and inventive” (Locus), and “just plain wonderful” (Booklist). My previous books are the science fiction noir novel The Body Scout and the genre-bending story collection Upright Beasts. If you enjoy this newsletter, perhaps you’ll enjoy one or more of those books too.

I really hate how "purple prose" has been used to describe ANY storytelling that happens to use vivid imagery. I remember absolutely seething when I saw a site label the iconic opening to du Maurier's Rebecca as purple prose.

Angela Carter, Clive Barker, and Francesca Lia Block are who moved me into being interested in fantasy and horror novels. And I feel that horror and fantasy can be some of the best places to play with style.

If you're writing a screenplay, then yes: the plot points are all that matters. The director and DP will supply the style.

If it's a novel, then style is 100% on point. If I just wanted the plot, I'd have AI summarize it for me.