If you’re on social media, you’ve seen the ripples of discourse from the snarky Wired profile of popular fantasy writer Brandon Sanderson. Much of the article, which wasn’t terribly well-written imho, focuses on Sanderson’s boring prose. I don’t have an opinion about Sanderson’s novels as I’ve never read them. I find his ideas about “Hard Magic” antithetical to what I enjoy in fantasy—magic should be weird and magical I say—but to each their own. The discourse did come around to something I’ve long thought about: the concept of “invisible prose.”

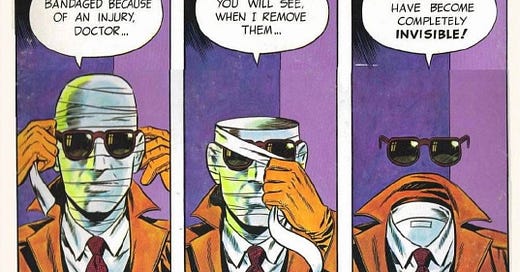

I’ve often encountered people who praise “invisible prose” as the aesthetic ideal. Often this is tied to claims that popular, commercial fiction is in truth better written than stylistic or lyrical prose that the snooty ivory tower elites allegedly enjoy. The former is what’s “actually popular with readers” and the latter is “literary masturbation.” A writer getting off on their own cleverness. One metaphor I’ve heard is that prose should be a well-Windexed window. The reader should gaze through the glass without noticing its existence. “Just give the reader the story,” these people say. “Get your sentences out of the way!”

I’ve always found this baffling. A work of fiction is prose. In the most literal sense, a story is nothing except its sentences. There’s nothing through the window. The pane itself is the story. It seems akin to saying “a listener shouldn’t hear the notes in a song” or “no one should notice the colors in your painting.” What does it even mean?

Of course, I understand to a degree. There is certainly prose that hews closely to generic writing we might experience outside of fiction—a standard that changes from time to time, location to location, milieu to milieu—and thus feels “neutral.” It’s perhaps similar to how certain haircuts or outfits draw less attention than others on the street in a given time and place. They’re still haircuts and outfits, of course. But you’re less likely to notice them. Or remember them.

And yet I don’t think this fully explains it. Because the very things that are supposed to make your prose "too visible”—elaborate metaphors, adjectives and adverbs, long sentences, a strong narrator voice, etc.—are all present in bestselling commercial fiction books. Consider some random examples from bestselling novels across different genres:

I feel his voice in my stomach. That's not good. Voices should stop at the ears, but sometimes—not very often at all, actually—a voice will penetrate past my ears and reverberate straight down through my body. He has one of those voices. Deep, confident, and a little bit like butter.

Dan’s heart took an enormous leap in his chest and his head gave a sudden terrific whammo, as if Thor had swung his hammer in there.

Her expression is one Luca has never seen before, and he fears it might be permanent. It’s as if seven fisherman have cast their hooks into her from different directions and they’re all pulling at once. One from the eyebrow, one from the lip, another at the nose, one from the cheek.

My skin buzzes, like my blood is made of iron fillings and his eyes are magnets sweeping over them.

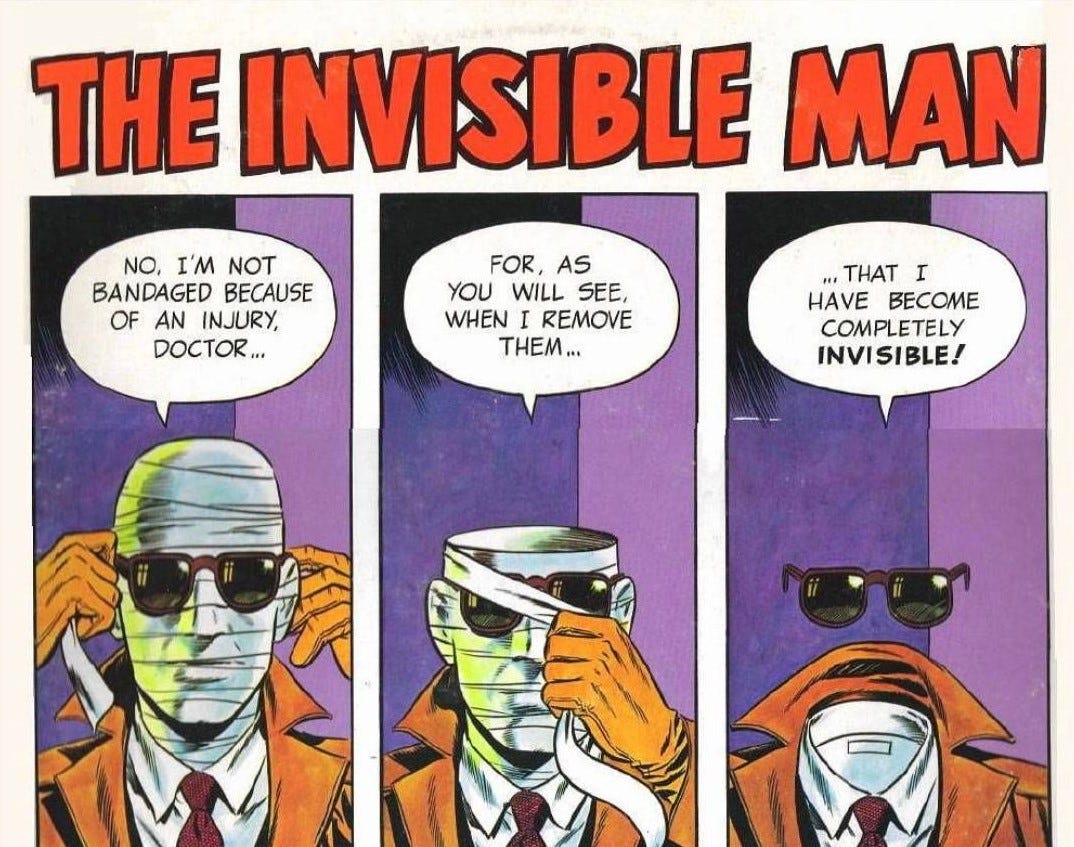

The monsters almost seemed to blend and shift together, one enormous dark force of howling, miasmic hatred as thick as the air—which seemed to hold in the heat and the humidity, like a merchant hoarding fine rugs.

Now, I’m not arguing these are all bad sentences per se. I’m merely pointing out that popular fiction is filled with writing that is visible in the exact ways that “invisible prose” fans claim to dislike.

(If you’re curious these are 1. Colleen Hoover - It Ends with Us 2. Stephen King - Doctor Sleep 3. Jeanine Cummins - American Dirt 4. Emily Henry - Book Lovers 5. Brandon Sanderson - A Memory of Light. I’ll add I’m a big Stephen King fan and think he’s capable of very lovely prose, but the above is a good example of how “visible” his writing can be despite his reputation for being “workmanlike” or “invisible.”)

Least you think I’m picking exceptionally bad examples, I’ll note the last came through my feed as evidence that Sanderson “is so freaking good” at writing prose:

Everyone will have their own ideas of what constitutes good prose. To my ear, these passages are clunky and the metaphors fall apart. (Merchants are typically known for selling wares not hoarding them, and air by definition holds the heat and humidity. Or is it the “miasmic hatred” that’s humid? Is this dark force notably soggy? It’s a bit unclear.)

Either way, why are these writers celebrated for having “invisible prose” despite having the hallmarks of “visible prose”? I think what people probably mean—but don’t want to admit—is that the above prose is not invisible so much as skimmable. The prose isn’t asking you to slow down and think, nor is it honing a specific aesthetic. These writers drop elaborate metaphors or complex sentences to signal dramatic moments just like any other writer… but the specifics might not matter. Indeed, slowing down to think about them might ruin the effect. Does Cummins actually want readers to stop and work out that fishhook facial expression?

You’re able to skim these passages and get the gist. These characters are getting horny. Those monsters are scary. This person feels bad. It’s the prose equivalent to a TV show you can watch on the background while doing dishes without missing much. And that’s fine. Nothing wrong with a good background TV show or a skimmable novel. I’ve enjoyed a few myself—especially good for audiobooks you listen to while doing other tasks.

“Visible prose,” by contrast, would be prose that’s hard to skim. There was a famous moment when Oprah interviewed Toni Morrison and said that she sometimes had to go back and reread Morrison’s passages to understand them. “That's called reading, my dear," Morrison replied. (And yes, I remember people getting mad and calling Morrison a snob.) Morrison later explained, “I took that to mean she felt forced to understand every word, its obvious and nuanced meanings, context etc.” That’s unskimmable prose. You have to be paying attention to fully understand it.

This doesn’t have to be dense prose. Chekhov and Carver may be minimalists with simple sentences but the words are carefully arranged. Metaphors are clear and sentences build upon each other to create specific effects. You have to really read them to experience them. This also doesn’t have anything to do with “genre vs. literary” debates. Tolkien is a very visible writer. You enter his world through the language. So is Le Guin, Chandler, Barker, and countless others. For that matter so are several of the authors I used above. Certainly Stephen King and Emily Henry are stylish writers whose work uses sentences to specific effects.

Ultimately, I think what people mean when they say they want “invisible prose” is that they—individually as readers—don’t much care about the writing at all. What matters to them is plot beats and worldbuilding lore that can be summed up Wikipedia style. Readers who complain about “unnecessary” moments that stray from the plot. Soon they might be able to just read a quick ChatGPT summary. Ideally, they can hold out for the TV adaptation.

And of course all that’s fine. To each their own. It takes all kinds. Etc.

But prose is composed of sentences. They’re never invisible. So don’t look at a house carefully constructed from sentence bricks and tell me it’s a pane of glass.

UPDATE 3/28: Since this post has gotten a bit of attention, I thought I’d just add a few more points that I meant to work in before.

1) A lot of popular commercial fiction today is largely voice-driven. Often a fun, semi-snarky voice that is perhaps reminiscent of your life of the party friend telling a story at a bar. But voice is entirely a function of prose. Of the sentences. Here’s the opening of the current #1 bestseller I Will Find You by Harlan Coben.

This is pretty skimmable prose I think, yet also prose that is “visible” on the page. The enjoyable voice of the narrator is a major pleasure of the text. It’s not a voice that’s “getting out of the way” to become a “clear pane of glass” to see the story. Hell, in this example we’re entirely in the character’s interiority.

2) I suppose it is also probably not a coincidence that writers who lean toward skimmable prose are also writers who produce at an enormous rate. To use Sanderson as an example, if Wikipedia is accurate he’s published TWENTY books since 2020. A couple of those are novellas, graphic novels, or audiobooks (which are maybe shorter?) but that’s still more than many writers produce in multi-decade careers.

Part of the reason Brandon Sanderson got profiled in the first place is that he wrote four extra novels during the pandemic—in addition to the ones he had under contract—and so decided to self-publish. You can certainly admire this productivity while also acknowledging that it’s going to be hard to write careful, considered prose at that rate.

3) Many genres of fiction are particularly prose-driven, where the “vibe” of the genre is carried out through the voice and atmosphere the sentences build. What would hardboiled / noir fiction be without the famous hardboiled voice? What is horror fiction without the atmosphere of dread? (Tom Houseman made that point in the comments below). What would romance fiction be without evoking the emotions of the characters through the sentences?

I’m reminded of Edgar Allan Poe’s famous bit of advice: “A short story must have a single mood and every sentence must build towards it.” Certain genres of fiction—many that are quite popular—are all about the mood or vibe of the story, which is always evoked through the prose itself.

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.”

Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

This is a great distinction, and I think you're really onto something here. Maybe we could say that people who claim to like "invisible prose" don't want the writing getting in the way of the storytelling? If so, I'm reminded of Cleanth Brooks's "The Heresy of Paraphrase." You can't rewrite a sentence of Gravity's Rainbow (or if you did, it would lose quite a lot). But with many other novels, you can rewrite lots of sentences and not lose much of anything, as long as you keep the general plot the same.

That said, my frustration with this debate comes from people (not you, but others) who think that pretty, elaborate prose is the be-all and end-all of good writing. There are plenty of great writers whose prose is relatively plain, and arguably fairly skimmable, but the perfect match for the stories that they're telling, and the artistry of the whole. Patricia Highsmith comes immediately to mind: you can't change a word of Ripley Under Ground, I don't think, without ruining that novel's dry wit, let alone its suspense. Which is to say that the "Heresy of Paraphrase" applies just as much to Highsmith as it does Pynchon, even though I suspect lots of people would think that it doesn't. But prose style is ultimately just one aspect of the larger art that we call fiction.

Oh I love this spin on the argument! (I literally spent my morning trying to write my way through my own thoughts on this — the dismissal of “literary” prose feels so...closed-minded).