Scattered Thoughts on the State of Book Reviews

rainy day thoughts on a rainy day

Last week, I wrote about “Criticism in the Age of AI” and tried to end on an optimistic note about arts criticism in general and book coverage specifically. This week, the discourse on that topic has been doom and gloom. Not because of anything AI-related, but because of the new New York piece, by Charlotte Klein, titled “Do Media Organizations Even Want Cultural Criticism?” The tl;dr is magazines continue to cut reviews of film, music, books, and other arts because they don’t help the bottom line: “Do reviews draw readers? Boost subscriptions? Sell ads? And if the answer is ‘no,’ how do reviews fit with both a publication’s identity and its quest to stay afloat?”

The answer is indeed “no,” as Klein goes on to say. Outside of something like a surprise Taylor Swift album or a major MCU movie, most people just don’t read reviews. Yet reviews still remain hugely important for books, at least the kind of books that we might call “literary” (whatever genre they’re in). An inventive science fiction novel, original horror book, or lyrical literary fiction book is sold based on critical attention and reader enthusiasm. It isn’t sold through paid advertisements, social media trope lists, or the ways more formulaic books with set audiences are sold.

My thoughts on reviews are somewhat scattered and contradictory so I’m going to go ahead and write this in a scattered and contradictory way.

had a great read on this discourse with “the decline of criticism, part two billion”: “Media organizations do not want cultural criticism the same way they do not want war reporting or fluffy opinion pieces as those specific things. They want those things as a way of getting what they actually want. The problem for writers and for editors is that there’s no way to teach the media organization to value what you value, because the media organization exists in Lovecraft space and does not have human values.”There is no reason to appeal to high-minded values when dealing with a tiny branch of a large corporation. Individual editors and writers can do what they can, but ultimately it will come back to traffic, ads, and profit.

One thing

points out is that younger writers don’t really aspire to write for a specific magazine, and this is in part because magazines are undifferentiated in the social media age. Up through the 00s, magazines still had different cultures or vibes. You knew you’d get a different reading experience with The New Yorker than GQ or Rolling Stone or Gawker or Vice or Buzzfeed or The Toast. But by 2012 or so, these distinctions were mostly gone. The need for endless online content to share on social media channels and capture search traffic eliminated the editorial oversight and curation that makes a magazine feel distinct. As a freelancer in the 2010s I knew, quite literally, that I could pitch the same piece to any number of magazines and never worry about whether the style or tone fit the culture.I suspect a major reason many people will pay $5 a month for a Substack subscription but who would never pay $5 a month for a magazine subscription is because here you do get a specific voice with specific tastes.

The problem for magazines is structural. In the old days, you subscribed to a few magazines and were likely to at least flip through the entire issue. you likely read some pieces that you wouldn’t have sought out otherwise. Early internet sites were similar. Readers visited the home page and would see a range of articles. But in the social media age, traffic comes through the sharing of links (or from search traffic) where the reader only sees the title and header image. Traffic depends on virality and search engine optimization (SEO).

Maybe magazines and newspapers should have focused on paywalls instead of search traffic. Surely they shouldn’t have fallen for traps like “pivoting to video” as Facebook and others changed their algorithms. Either way, this is the situation journals find themselves in today as print subscriptions continue to dwindle and social media sites work harder than ever to keep users on their apps instead of clicking to outside links (a major reason companies like Google are invested in AI).

The problems people have with book coverage—enormous “anticipated” lists, the listicle review format, clickbait headlines to author interviews, essays “pegged” to a book that don’t really discuss the book—are all downstream from how social media works. Those things get traffic. Traditional reviews do not.

For a few years, I edited Electric Literature’s website and we spent a fair amount of time looking at the analytics and seeing what posts got traffic and which didn’t. Reviews got very little compared to any other type of coverage. One fact that surprised me was how many people would “share” or “like”/“fav” an article before even clicking the link. Which articles went viral was largely determined before anyone read the piece, based on what title and header image grabbed users’ attention. Knowing that, it is easy to understand why “Book Review: A Debut Novel by Some Random Author” will get far fewer shares than “The 10 Scariest Vampire Novels of All Time.” If you like vampire novels or horror in general, you might “like” a post based just on that headline. Even if you don’t read it, you help it rise in the algorithm. But unless you happen to know Some Random Author, why would you share that or even click through?

If no one really reads reviews, do they matter? Yes. In addition to the fact that criticism is an art that is valuable in itself and how it can deepen our appreciation of other art, reviews do affect how a book performs. Less so today than in the past, but they still matter. Reviews influence what books are stocked by booksellers, what books win awards, and what books readers become aware of. They are especially important to any work we might call “literary”—in whatever genre. Science fiction books pushing boundaries, innovative horror novels, stylistically interesting autofiction works, or anything new and challenging will always be harder to sell to the public than formulaic work in established niches.

You may be inclined to say “good riddance to the snobby and evil gatekeepers!”, but remember that what replaces professional reviews is not unbiased assessment or artistic meritocracy. What replaces it is money and fame. Marketing dollars, social media followers, online fandoms (easily manipulated by marketing and publicity) determine sales today. Our culture of forgettable formulaic bestsellers, endless film franchise “universes,” IP reboots, and so on is the result. Professional reviewers can have their problems, but they are more likely to offer an honest assessment than a billboard advertisement or army of “stans.”

And let’s be honest. Most books sell very few copies. Reviews can be extremely meaningful to an author. The kind of thing that makes you keep pressing on. A little bright flash of recognition during your long nights of the soul at the keyboard.

While I think book reviews are very important, and have written many myself, I will admit that the traditional book review has always seemed a somewhat odd beast. It sits in a nether zone between critical appraisal, “buy or not” recommendation, and summary. I often find myself only reading reviews of books I’ll never read—rubbernecking a pan by a critic I like, say—or else holding off on reading reviews until after I’ve read the book. I don’t want to read the whole plot summarized or have the reviewer’s critique color my own read. I doubt I’m the only one.

The standard book review—400-800 words, mostly summary with a few sentences of evaluation, published around release—is the same as reviews for other things like movies and TV shows. But the consumption of books is very different from those art forms. Only a few movies are released at a time, their run in theaters is limited, and the time commitment for a film is small. A movie fan might reasonably read reviews of every new theatrical release and decide which one or two to see. In this way, a movie fan can watch every release they’re interested in throughout the year.

Books, on the other hand, are published in far larger numbers, have no limitation to their run, and the time commitment is (typically) longer. Perhaps an avid reader has a couple favorite authors whose new works they’ll rush to read on pub week. But most of us, I think, have a huge pile of books we’re hoping to get to and are likely to read a new release weeks, months, or even years later. Traditional book reviews are shaped like traditional movie reviews, but don’t serve the same function.

—a great critic and author, who I interviewed last year—points out one problem in review coverage that could be fixed (at least more easily than something like “how social media traffic works”). Book reviews don’t have to be so timed to release date. For a few lucky authors, a flurry of review coverage around press day can help propel a book. But overall, this focus hurts everyone involved. As Taylor says, most authors get all their media in a week and then crickets. The concentration of reviews can burn out readers—the old marketing adage that “a customer has to see something 7 different times to buy it” works better 7 times over three months than 7 times in one day and then never again—and also makes it harder for critics, who have to pitch reviews in a small timeframe. And it probably also hurts web traffic. How many reviews of X author’s book can one expect to read in a week?So, a small thing that could have a big impact is divorcing book coverage from pub date. It would help good books to get more coverage over a longer period, and it might even help magazine traffic too. (Although only a little, admittedly. Book reviews will never be huge traffic draws.)

Reviewers with their own platforms, like, oh, a Substack newsletter, should also feel very free to review a book whenever they enjoy it. There is no need to worry about pub dates. Yes, I will try to take my own advice here.

In

, has a great piece on navigating small presses and big presses as an author. One quote that stood out: “There is very little interest in developing a long-term relationship with a midcareer author. The industry is obsessed with debuts because they know (or think they know) how to market an “emerging” voice.”Just as with the unnecessary focus on pub date, there is an unnecessary focus on “debuting” in books coverage. This has led to absurdities like established authors being pitched as “making their [marketing category] debut!” Sometimes I think an author could go a whole career writing nothing but debuts. “His debut story collection was followed by a debut science fiction novel and then his debut memoir before his debut autofiction novel and…”

What else could improve book coverage for periodicals? This might be heresy to say, but perhaps the 400-800 review should be deprioritized. If you are reading for critical appraisal, then longer reviews that might survey an author’s career to date—the kind places like Harper’s and Bookforum and for that matter New York still do—are preferable. If you are reading for “what should I buy?” help, then perhaps short list review format grouping some titles together with 200-400 words each (“Three Dystopian Novels to Check Out this Month) is actually better. More readers will click on that, and the author and publisher still get the key thing from their POV: a pull quote.

(Though it is more work for the reviewer to read five books instead of one and reviewers are underpaid already.)

Another thing magazines might do is focus on building a specific culture and community that will have subscribers reading the magazine not just links they see on social media. Easier said than done, surely, but still.

And perhaps easier done on Substack than in a magazine. The benefit of a newsletter is that readers care about your voice and are more willing to follow you in whatever interests you, regardless of considerations like pub dates or “buzz.” I’m already reading more reviews on here than in most magazines, because critics here feel a lot more free to shake up the format, length, and style of reviews. I quoted

’s response above, but the other BDM post I read this week was an article about an old Ursula K. Le Guin science fiction anthology that discussed ideas of canonization in general. I also read survey the Western (with books published between 1912 and 1969) with commentary on modern writing.These writers, and others here, are taking advantage of the freedom newsletters offer to do criticism in different ways without worrying about release dates, debuts, author buzz, or anything else. It seems like a better model. Certainly a more interesting one to read.

Okay, that’s all I have. No easy solutions here. But the main thing is to read books, review them if you can, and share them where you can.

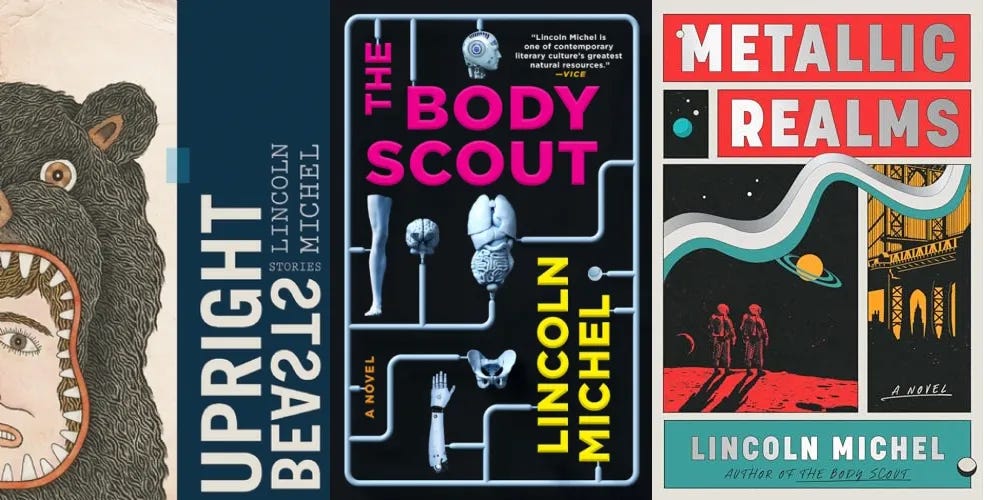

My new novel Metallic Realms is out in stores! Reviews have called the book “brilliant” (Esquire), “riveting” (Publishers Weekly), “hilariously clever” (Elle), “a total blast” (Chicago Tribune), “unrelentingly smart and inventive” (Locus), and “just plain wonderful” (Booklist). My previous books are the science fiction noir novel The Body Scout and the genre-bending story collection Upright Beasts. If you enjoy this newsletter, perhaps you’ll enjoy one or more of those books too.

People still belong to book clubs. Dare one fantasize about a book club app, a Books With Friends, that would automate and standardize the book club experience, with templates for quickly summarizing what people like and dislike?

Dare one fantasize about a better version of Goodreads that isn't just an opportunity for people to trash authors they haven't read because they don't like what they've heard about the author's politics or lifestyle?

Should every book order spawn "tell us about your experience" emails like you get every time you go to the hospital or buy a pack of gum?

Or is all this stuff already happening and I'm out of the loop?

Agree wholeheartedly with the idea of not bunching reviews just around pub date. One of the newsletters I love is CrimeReads, which daily features 5-8 short essays about books/films. Yes, some are "new thrillers publishing this week" but often they are more along the lines of "Six Novels that Feature Unreliable Narrators" or "9 Films Where the Journalist Saves the Day" and often feature works released years back. It's where I discovered (and bought) Blake Crouch's "Pines" (2012) and got introduced to early firms by Bong Joon Ho