Processing: How Jeff VanderMeer Wrote Absolution

The author on the importance of structure, revision, and writing "in the grip of an ecstatic vision."

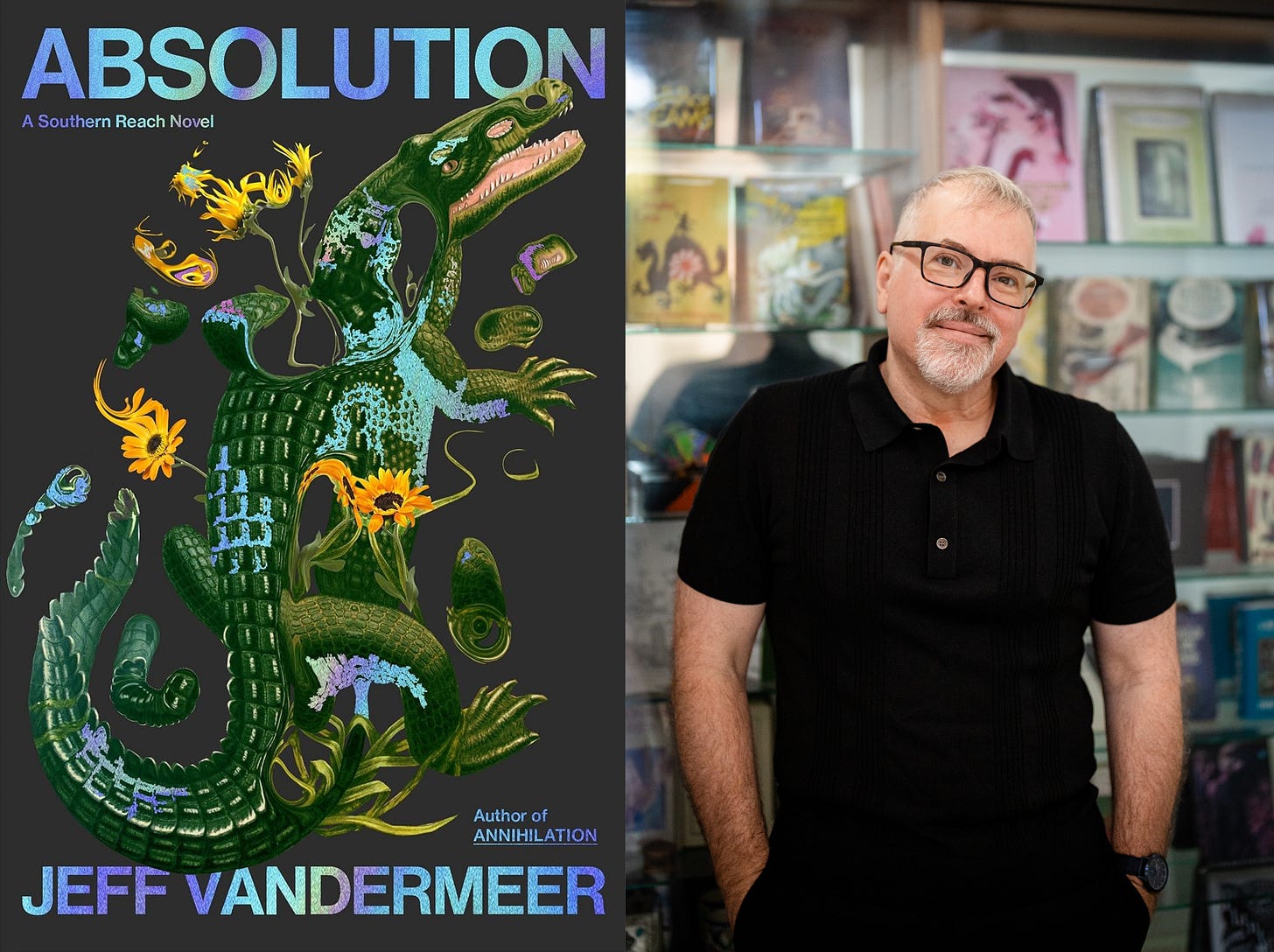

On a semi-regular basis, I interview authors about their writing processes and the craft behind their books. You can find previous entries here. This week I’m very excited to be talking with Jeff VanderMeer about his weird, wild, and triumphant return to Area X in Absolution. A decade ago, VanderMeer introduced readers to the uncanny realm of Area X with the eerie eco-horror novel Annihilation, which was followed in the same year by Authority and Acceptance. Although the bestselling trilogy left lingering questions, it seemed to be complete. But this week VanderMeer publishes Absolution, a novel that answers some of those questions while providing a bunch of strange new ones. The novel is told in three parts chronicling three different investigations into Area X over the course of a few decades, serving as both a prequel and sequel. Like the original genre-bending trilogy, Absolution mixes styles and forms, feeling like a creepy John le Carré spy novel at one moment and surreal body horror phantasmagoria the next. There is also a section with likely the highest FPP (“fucks” per page) you’ll ever read. Absolution will certainly reward readers who first refresh themselves on the Southern Reach novels. But it is also a strange, lyrical, and really fun* read on its own.

* At least if you have a high tolerance for body horror and nightmarish rabbits.

I chatted with VanderMeer over Zoom about writing the novel, being inspired by dreams, and writing "in the grip of an ecstatic vision."

You were public on social media about the creative torrent you experienced while writing Absolution. You wrote 350,000 rough draft words in about four months. I think you also said that at one time you had to pull over the car to jot down notes because ideas were coming so fast. Just how different was writing this novel from your normal writing process?

Good question. In some ways, it was very similar, right? It cracks me up to have to describe the process, because, especially when you’re leading a creative writing workshop, it is not very replicable. Novels usually start for me as dreams. That’s because I tend to feed my subconscious ideas consciously. I feed the things I want to write about and then they come out. Obviously, not in the ways I expect. But I also devote a lot of time to learning technique. When I’m writing a novel, even one like this, if I’m reading another novel, I might plug in a technique I just saw used by somebody else in an unusual way. And then take it out again. Just to see how it works. It’s a weird combination of the subconscious process and very conscious mechanical process too.

The short answer to your question is unlike anything else, just because of the length. Annihilation was similar. It took six weeks to write that novel, which is kind of ridiculous. But similar in being in the grip of an ecstatic vision. I’ve been talking about this because we often don’t want to emphasize that, not irrationality, but that inability to pin down what you did and how you did it. Having done some interviews like that, it’s good to talk to you, because as you know, once you have something on the page then you’re coming back to it in your head. You’re already revising it in your head. You’re already doing all these conscious things. That’s probably a long answer to your question. But like, and unlike. Just the period of time was exhausting.

The first three books all came out in 2014, so a decade ago. When did the idea first germinate to return to Area X?

Probably in 2017. I had this idea for a dark fairy tale retelling of an expedition of biologists. I wrote the first few pages of it, and I really liked it. But I also felt like to sustain that tone I needed to know more. I needed to think about it more. And so I set it aside, thinking I’ve got this perfect fragment—the first four pages of Absolution are pretty much that—and I don’t want to ruin this. I want to think about what this means. I had other little bits and pieces of Southern Reach stuff that weren’t quite working but were teasing things out in my imagination about Central, the CIA-like agency, and what that means about dysfunctional systems. All the systems that we work under. Of course, that’s a very abstract thing. It’s like you have to feed that into your subconscious to make it organic, coming out through characters and situations.

Then I read part of that fragment at a convention last spring, and something about that began to energize me. Hearing it out loud, hearing the rhythm of it. July 31st, I just started writing. I had it all in my head. I had the entire structure in my head. That’s the way it often happens. I think about something for a long time, and suddenly muscle memory comes in, all this other stuff comes in, and you have it. I think the biggest key was realizing how it was mediated through another point of view, which is Old Jim going through these files and kind of creating this experience for you. That excited me. The layering, from a craft angle, excited me. That also led to, Oh, this is how this proceeds into part two of the novel. And then, in a way, part three. So that gave me everything basically.

I guess you answered my next question, which is how much of the structure did you know going in? Is it typically the case that you have the structure in place before you start really drafting?

It’s really important to me to have the structure. Even if it’s a scaffolding that falls away and something else occurs. Talking about structure in general, there are two things. One, when you write in a surreal mode, like I can, you need to—or at least I need to—have a pretty strict structure to pour that into before I start writing. Because my concern is that the surface of the prose can sometimes read like dream. If you have that and you don’t have a strict structure, then it just kind of floats away. The second thing is that in terms of completing the novel, I was really thrilled by the structure, because it allowed me to have three very different styles in play. Meaning, if I got tired of one, uninspired by one, or whatever, I could switch to another. I was writing all three parts simultaneously, and then figuring out where information went. The structure kept me fresh throughout the six months.

Speaking of different styles, one thing I really admired in the Southern Reach Trilogy was the way each novel was different from the previous one. You switch POVs, styles, and even genres. We go from a short ecological horror book with Annihilation to a longer novel about bureaucracy with Authority and yet another thing with Acceptance. As you said, Absolution includes three sections in three different styles. For the original trilogy or this book, did you ever get pushback? Was anyone saying you should make it all more straightforward for readers?

When there were offers on Annihilation, there were ones that disqualified by themselves by saying, “This needs to be an epic love story about a woman trying to find her husband.” That would have betrayed the entire underpinnings of that novel. What I have had to do is be patient and realize that this particular series—unlike, say, the Borne series—is about giving readers what they need and not what they think they want. That has worked really well. For the 10th anniversary editions, I’ve seen a lot of people who loved Annihilation and were kind of thrown by Authority go, “Oh, now that I’m reading Authority as its own thing I really like this.” Some portion of readers are always going to bounce off the different approaches and prefer one over another. But one thing about the books is that they are meant literally to be reread. Even the way you view characters changes by the end of Acceptance. If you go back and read Annihilation, your experience of the characters, knowing what you know now you know after reading the three books, is completely different.

Absolution is even trickier, because it’s kind of a prequel and a sequel at the same time. But the sequel part is mediated through a point of view you may not trust. If you’re puritanical, you may not even get through that section. It’s been interesting watching on Goodreads, the fight between those who love the “fuck”s and the Lowry section and those who are passing a moral judgment. It’s been interesting to see how the way you place answers in a text affects the readers ability to believe them. And how in this series, it is usefully destabilizing to put them in the place where the reader has to decide whether they want to believe it or not.

What you’re saying feels very thematic with the whole series, right? Area X is this shifting, morphing, doppelgänger-filled space. And our understanding of the answers and mysteries changes throughout the reading experience. You mentioned giving readers what they need, not want. I was reading some reviews before this interview, and many of them said—in a positive way—that the book gives fans lots of answers… but then a whole bunch of new questions.

And I think that’s the way the world works for most people, right? I say I write surreal fiction, but in some ways, I write very realistic fiction. In terms of how we perceive the world, how we process information, how we often have to collate or collect facts by synthesizing two or three different points of view on the same event, right? I think readers have given me permission to do that too. If this was a standalone novel, I might have felt more pressure. I felt like a freedom, because readers have been so cool in terms of applying their imagination more than you usually ask a reader to do. There’s some guy on Goodreads who keeps giving me one-star reviews for these novels, but he’s read every single one. He can’t get him out of his head. There’s a kind of maddening quality for some readers that’s entwined with something that keeps them reading. I always point to Borne as the example of giving readers what they wanted and needed, because I can do it. But the nature of this series required a different approach.

You’ve alluded to the third section of the book, which is in the POV of Lowry and has some of the most creative uses of cursing I’ve ever read. It comes a kind of surreal, dirty, “fuck”-filled poetry.

[Laughs] Thank you. It was meant to be kind of funny.

I thought it was quite funny. I remember literally laughing out loud at the dialogue on the last page of the book, although I won’t spoil that here. Okay, so there’s a lot of curses, like you said, and some readers might push against it. The character is also what you might call—I’m putting this in scare quotes—“an unlikable character.”

Yeah.

How did you get into the mindset of that character when writing? Did you extemporaneously speak his curses aloud? Or something else?

There were a couple things. There’s an academic paper by Dr. Alison Sperling called “Second Skin” from 2014 that really stuck with me about permeability and contamination between the body and our environment. That was key to Lowry’s character. The idea he has such a reaction to having to put on a suit to go into Area X—which is itself contained under a suit, if you think about it—was key to thinking about him. Added to that was the idea that he’s on these experimental anti-anxiety drugs that make him curse. Then you know that you can maybe trust him less when he’s cursing, because he’s on the drugs. He’s off the drugs when he’s not cursing. That gives me interesting ways to mediate reality in that section. Then the fucks become this thing that is telling you something about the reality of how he’s viewing things and whether you should trust it or not. There was also something about the pulse of his cursing that was key to the character. Like the character can’t exist without it. That allowed what I would call the kinetic energy of the narrative to be sustained. It is something I wrote almost in one go. Every time I picked it up, the music and the progressions of it were perfect in my head.

There were the things that allowed in terms of his character. He’s unlikable, but he’s also the only person on the expedition who actually does anything. He always takes action. I set up, hopefully, the situation where the reader maybe doesn’t like him but they still are like, “Oh, he actually tried to do something!” That’s useful in terms of how we think of characterization, because we’re often led astray by characters that are active. We sometimes misinterpret action as being just generally a positive thing, right? As opposed to a character who doesn’t do anything. And we’re also driven as writers to write characters that do things, because that’s the easiest way to generate narrative. I found that kind of dichotomy interesting. Then the unintentional humor that’s generated by his personality was extremely useful in getting me to a place where I could explore some really transgressive moments that played straight would not have worked. There’s a scene where he’s contemplating eating something. That is a scene I couldn’t have written without the fucks, without the inadvertent humor and all the rest of it.

I remember that eating scene quite well! I put “unlikable characters” in scare quotes there because it’s such a strange concept, right? Many of my favorite characters to write and to read are assholes or buffoons or weirdos.

Right, right.

You mentioned the humor, and I did want to ask about that. Absolution is filled with some really frightening and surreal and beautiful horror moments. There are a lot of creepy moments that have stuck with me, like the rabbit eating crabs in the beginning. At the same time, there’s a lot of humor in the Lowry section and in other sections. I felt there was a great playfulness in the book. I could see you having fun on the page. Maybe an example is the chapter titling. “Love and Glory Holes,” “Slinky-Dinky Pinky-Winky,” “Not Enough Fucked-Up Stuff in Barrels.” How do you balance horror and humor, or playfulness, when writing?

That’s a good question. To talk about the chapter titles slightly, when I do include chapter titles, there’s a real purpose. A lot of the chapter titles in part two are riffing off 70s and 60s songs. That’s in part because I don’t have those time period references in that section, but I wanted to have a reference to it.

I’m glad you mentioned fun, because I love writing the uncanny stuff. I just love it to death, to the point that I had to cut 20,000 words from part two because I was having too much fun. One thing about the book that people may not expect is that it’s a pretty entertaining text, even as it’s dark. Part of that is the humor. I don’t like a monotone in a book. If I read a horror novel and it doesn’t have some ameliorating effect other than the horror, it begins to seem like everything is the same. I remember my former agent, Howard Morhaim, on one of my Ambergris novels, saying, “I really love this dark noir. But if you’re going to show that, you’re going to have to show us why we should care about what happens to this place by showing us something positive, or some vision that that is more upbeat, so that there’s that contrast.” I think in this book, the humor serves that purpose. Also, that’s the way human experience is, right? Even in our darkest times we make jokes. Finding the level is important.

I totally agree. I always like horror mingled with humor, and need that tonal variety. To get into the gritter details of your process. I mentioned you said you wrote 350,000 draft words. Can you talk about editing and how it got trimmed down?

It was really the middle section. “Dead Town” kind of had its own inexorable, fated cycle to it. It has an inevitability to it, at least it did when I was writing. There were a couple of things I re-sequenced. There’s a section where Old Jim has a rumination about time, and what is supposed to do is make you take a step back and see a wider picture. That was in the wrong place. We had learned something really terrifying. Then we went to this thing that was in the place it was not right. I re-sequenced it so it was more in line with the progression of the hurricane occurring, and more about that. And then the ruminations opened it up in the right way. Sometimes it’s just about the progressions.

In part three, the revision was mostly about how much time we spend in base camp. There’s a lot to unpack at base camp but ultimately I needed to get them on the road. I cut a fair amount from that section, even though I thought it was funny commentary about expeditions and all kinds of stuff. It just didn’t serve the narrative emphasis.

Then part two, it was about how much of Old Jim’s investigation into what’s happening in in that area. You know, it’s like a few months before Area X comes down at the border. How much of it needs to be on the page? How much of it can be summarized as information that’s learned? There was also his relationship with Cass, and what that means, given that she’s not exactly who she seems. I had a scene that was him going to Cass’s apartment much earlier and them having a conversation. It was a long-ass scene. It was meant to establish a further friendship between them. But what it wound up doing is slowing down the narrative and doing the opposite. The more I put on the page, the less their friendship seemed genuine or real. So, what I did with that scene is I took it out, and I took the information we learned in there and distributed throughout the novel.

Yes, I love how you bring up the question of the order of information and where information goes. I feel like is one of those craft elements that’s so important as a writer but that’s often something younger writers don’t think about. You need to think about the reader not in terms of pandering to them but in thinking about when they are getting information and what the effects are.

It’s absolutely huge to me. A good example is a novel called Light by M. John Harrison. He does an amazing job of giving you what you need. It’s a space opera giving you what you need about that future setting at the moment that you need it in a way that’s interesting. Sometimes you don’t need all that upfront, and it kind of clogs the arteries of the novel. I need this here, there, or the other.

And all in a long prologue.

Right, right, exactly. I almost had a prologue of this novel, which would have been a mistake. A secret file that gave more context. I was like, no. They’re going to just have to go on this expedition and see what happens. The structure really helped me with regard to the information. I’d be working on “Dead Town,” and I’d have a reveal or something. And I’d realize, oh, actually, that goes in Lowry’s section in part three. I kept pushing things. Some things I pushed up, some things I pushed back. And I think that really helped unburden the narrative from being slogged down in information.

With part two the biggest challenge for me was what is actually necessary? I was getting into a le Carré zone of interiority and layering. At one point, I realized, oh, I have so much interiority with Old Jim that I can cut it back. I can move this to Lowry’s section. It really depends on how you think about pacing and whether pacing is natural to you as a writer. You can artificially learn pacing just by re-sequencing scenes, experimenting with where you cut a scene. You can learn it that way. One thing I think I’ve internalized is this idea of pacing. When the music is off, when the progression is off, I know it. And that’s the point at which I have to reconfigure a scene, rethink what the order is. When I’m asked to unpack it and analyze it, it’s hard because I just feel it and know that it’s wrong, and then I know when it’s right.

That’s how it works, right? But like you said it’s also craft based. You read other authors, you study things, you try techniques, and then it gets internalized into some narrative goo in the mind.

Right.

I was curious about the role of scientific research in this book. On the one hand, it’s a very surreal novel, but on the other hand, there’s a certain amount of research that went into it. You mention a few scientists you consulted with in the acknowledgments, for example.

Yeah. I think that I lucked out because I have been more and more outsourcing things. For Hummingbird Salamander, I had a biologist come up with the imaginary salamander and hummingbird and then reacted to the entries and information they gave me. It was amazing because she, as a biologist, put in jokes and illusions in there that I would never have thought of and that I could respond to in the text. Here, that happened inadvertently. One thing about it flowing so well was that I was scared shitless that if I stopped for a moment to do research, I would lose the music. I would lose the progressions.

I asked a friend at FSU to recommend a research assistant, and, thank God, they recommended this person, Andy Marlowe, who unbeknownst to me was like the most decorated undergrad at FSU in their English and art department in the history of the entire university. Knew German, so they could translate Schubert’s lyrics for me. I needed Schubert’s lyrics for Old Jim’s sentimental piano music thing. And they could do art for the book and could do research. Once I knew all this, I gave them a lot of leeway to bring me back stuff fully formed in a mode where I would synthesize it myself. They did some scientific research and then research on CIA experiments in the 70s, which was really useful.

They also did this thing that didn’t exist, which was there was no overlay of important environmental sites on the Forgotten Coast with abandoned plantation sites, other colonial sites, pre-colonial sites—that database did not exist. That was really important to me, even more than the scientific research. But it was a kind of scientific research to know the history of each place that I was writing about, even if only an echo of that or a little tiny hint of that got into the narrative. It was fascinating to have an external brain that brought it to me in a form where it was already ready for the novel. Andy is also a short story writer so was very close to being in collaboration. I joke that I’m lazy, but I think it’s about authenticity and understanding that there’s things where I can have a subject matter expert react to the novel but it’s more organic to have them actually participate in the novel. I can’t point to specific effects that are better in the novel because of Andy’s influence. All I know is that it’s a richer, deeper piece because of the way we interacted on the research.

My last question is what advice would you give to an aspiring writer of the weird, the bizarre, the surreal?

There’s such a long tradition of it. First, know your history. For me, it was easy. I was asked to co-edit a whole anthology called The Weird that allowed me to learn what I what I had not known. Also, one thing that is important is that it’s still about the same things as any other kind of fiction. It’s about the characters. It’s about having the right structure in place—whatever that means to you, whether that means plot structure or something else. And following your own obsessions and your own personal likes and dislikes, even at a very tactile level, is really important to creating effects on the page that are disturbing. I was just talking to Victor LaValle about how Brian Evenson is really great to read because he’s constantly surprising in terms of how he writes this kind of fiction.

Ah, I love Evenson. I’m in the middle of his new collection right now.

Cool. Yeah, he manages to unsettle both me and Victor on a regular basis, even though we’ve read so much of this fiction that we're jaded. So, I think just colliding yourself on it. Then also recognizing that there are certain effects in horror movies and weird movies that can be translated into fiction in a useful way. Not like jump cuts and crude stuff like that. But I pull from movies all the time in my fiction, I just try to translate it in such a way that it’s interesting in terms of craft and not just about scares or something like that. It can be very psychologically interesting to translate the texture of certain films into fiction.

The interview was edited and condensed for clarity.

If you enjoy this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout—which The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent”—or preorder my forthcoming weird-satirical-science-autofiction novel Metallic Realms.

Wow! So cool that you got to interview VanderMeer. Love his books and his whole vibe and rewilding project.

Superb interview. Big fan of Jeff's, even though sometimes his work gets a bit too experimental (I'm looking at you, Dead Astronauts). Southern Reach is superb and I'm looking forward to reading Absolution, and I'm fairly certain I'm going to have to purchase those 10th Anniversary Editions because those book covers are divine.