Processing: How Helen Phillips Wrote Hum

The author on subtle worldbuilding, artificial intelligence, and the importance of community in the face of dystopia

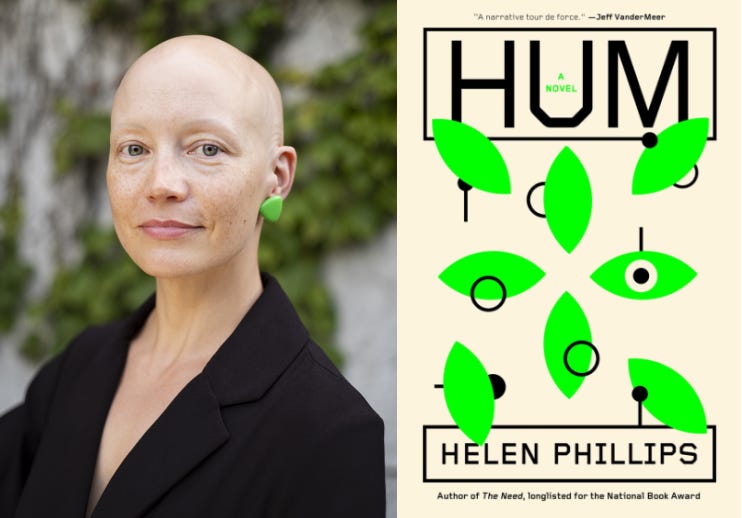

On a semi-regular basis, I interview authors about their writing processes and craft practices. You can find previous entries here. For this entry I talked to Helen Phillips, whose excellent new novel Hum came out last week. Similar to Phillips’s previous books, such as The Need and The Beautiful Bureaucrat, Hum strikes a skillful balance between wild speculative ideas and a realistic portrayal of family life. Hum imagines a near-future where climate change rages, the gig economy is even more exploitative, and A.I. robots called “hums” are omnipresent. Within that world, she tells an intimate and realistic portrayal of a family struggling to get by.

I talked with Phillips in-person for her book launch at Greenlight Bookstore. This conversation has been cleaned up and condensed from the transcript of the recording.

I thought I might start by asking you about the end of the book, or more specifically, the endnotes. At the end of Hum, there are a series of endnotes that list news articles and statistics and facts that you read during research that helped inform the book. I wanted to know how you created the world of Hum and the interplay of research and the worldbuilding.

When I am starting a novel, it's usually that I'm anxious about some things, and writing the novel is a way of exploring and processing those anxieties and learning more about them and trying to face them. So, when I was starting to think about this book, I was anxious about climate change, artificial intelligence, and social media, and the future that we are constructing for ourselves, or that is being constructed for us. And so, my first step in that process was reading a lot about those things, reading about climate change. I had a bunch of notes, like 100 pages of little scraps of overheard dialog, or newspaper headlines or images that were in my mind. After I had Magpie-gathered a bunch of things, the next step was to just do a lot of reading. The first months I was working on the book, I was actually just reading a ton. I read, in terms of climate change, The Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace-Wells, and also some of his reporting. I read a really interesting book called The Artist in the Machine by the writer Arthur I. Miller. If you're worried about AI, you maybe should read that book, because it takes a slightly rosier view of how we might positively collaborate with artificial intelligence. Tomorrow night, I’m at The Strand with Kashmir Hill, who has done some phenomenal reporting about the surveillance that we are all under. She just did a piece about how our cars—well, I don't have a car, so I guess I'm fine—but your car tracks you. If it's connected to the internet, it's tracking you. So, this is a long answer to your question, but I did a ton of reading. And then time passed. When I started doing this in 2019 there was no ChatGPT. I was reading articles about the precursors to ChatGPT. It’s weird writing speculative or science fiction now, because the world, faster than you can write a book, starts to catch up with you.

When I wrote my own near-future speculative novel, I remember being shocked by certain things I wrote that I thought were maybe too ridiculous, that I shouldn't put in the book, then came to pass. Because there’s a lag between writing and publication and the world moves so fast. Since you turned in Hum, has there been anything that surprised you that has come true or realized some of what you were worried about or excited about?

One moment that felt that way was when we had the really bad air quality because of the Canadian wildfires. That stood out to me because in the book, the daughter, who is eight, is very preoccupied with air quality. And that is actually something David Wallace Wells has said, that people are preoccupied with ocean levels, but rising air quality is a big one to worry about. That felt dystopian, when the air quality in New York City was 450 AQI. I thought it would be a while before I'd see New York with such poor air quality.

Yeah, you can't really escape the air.

You can't escape the air.

To go back to the topic of worldbuilding, I really liked your light-handed approach to worldbuilding. You have a lot of interesting science fictional technologies. There's kind of virtual reality pods called “wooms” and the children wear smartphone-ish devices called “bunnies.” But you mostly give us the names and the gist of these technologies instead of long-winded explanations. You let the reader fill in the rest. What’s your approach to worldbuilding?

Yes, I think worldbuilding for me is the most powerful when it's the most subtle. When it feels, in a very organic way, like just the setting in which the book is taking place. I did write a book that was twice as long as this book, and then I trimmed it down to arrive at Hum. Maybe some of that more in-depth worldbuilding was there, in the longer draft. I find that the more it is lightly referenced or just seen out of the side of the eye, it's more convincing for me as a reader. And so I really try to do that with as little as possible, just to indicate this alternate reality.

Another answer to that is that this book is sort of an alternate reality, but it is very seeded in our own reality, and you can see that in the articles I cite at the end. So, is it worldbuilding? I mean, yes, but it is really extrapolating from the world around us. I think imagination is such a critical part of being human. It's very easy for me to see something and look at it askance and it suddenly seems really dystopian. It's all around us.

One of the more science fictional elements are the hums, which also provide the title. Can you talk about why you chose the title Hum?

Sometimes my titles have been so hard. Like for my last book, The Need, I named it right before I was about to try to seek a publisher. It came so late in the game. But with Hum, I was lucky. As soon as I knew that the robots would be called hums, I knew that that would be the title of the book. It was a title that I loved. I love the physical appearance of it, and I love the word hum. I like the word hum because it contains this duality, which is really important to the book. On the one hand, I think of hum as referring to all our devices, with this constant low simmer of social media, and all the machines around us that make sounds, and the hum of traffic. So, it's kind of negative, like a sound that you can't get out of your head. But then, on the other hand, humming is something you might do for your child at night. It's a soothing sound. It's a nice sound. You might hum while you're doing the dishes. Hum is related to the sound of om, the sacred sound. So that duality of the annoying or even the sinister, and then the comforting and the warm and the wise. I wanted the hums to embody that and the title to embody that.

I think they do. It reminds me of how in the galley, you have an intro note where you say that you didn't want to create “a sheer dystopia.” You wanted to present the complexities of these issues.

Yes, when I was setting out to write this book, I explicitly said to myself, I don't want to write just a dystopia. It becomes easier to write dystopia as certain dystopian things happen, and it almost feels irresponsible to me.. I want to at least have some seed of how we might navigate it, or how we might move forward. I always give myself obstructions or challenges for my books, and one obstruction here was it must not be a full dystopia. Maybe it still is, I don't know, but I was really trying to have some seeds of hope in there.

I think you achieved that. Even the hums in the novel are at times nicer or helpful.

Although people have told me that the nicer the hums are, the scarier they are. But yes, I do believe so. One thing the hums do is they're constantly advertising. You'll be in the middle of what feels like a deep conversation with the hum, and the hum will be like, “you should buy these earrings,” which for me, creates a lot of humor in the book. But you can pay a lot of money to turn off their advertising feature, and when you turn off their advertising, they become capable of really engaging with you in a meaningful way. So that's one suggestion. Could we have more interaction with AI that isn't beholden to some kind of capitalist interest? That's just a thought.

Speaking of the hum advertising interruptions, one of my favorite moments of the book is when a hum demands that May, the main character, allow a cheek swab for a DNA test. Without spoiling the plot, the reason is quite creepy. But then in the middle on the interaction the hum says, “If I upload your DNA data to TEMPerature™…you will receive a complimentary TEMPerature™ thermometer. It will send your temperature to your doctor at regular intervals. Do you approve this transaction?” It’s one of these moments with such a perfect mixture of the creepy horror of our modern dystopia along with a kind of chipper capitalism. I agree it's very funny. I guess my question here is, how do you balance humor and horror in your writing? Because I feel like those kinds of moments embody both humor and horror.

I'm glad you saw the humor in it. A review in the LA Times last week mentioned that it's a funny book, which really meant a lot to me, because it is kind of a dark book, and that tends to get more play. I think that as I'm writing, I need the humor. It is hard subject matter and so those little jokes or those little funny moments are important to me. I think they do spring pretty naturally out of the situation. Like, it's weird to talk to a robot. It's weird to have a robot giving you advice and advertising to you at the same time.

And it's also very real, right? We experience that all the time now, even when it's humans. I listen to a podcast and halfway through it like, “This murder mystery is brought to you by Shrimp Float, the shrimp-flavored ice cream floats!”

That’s true. That is similar. You have the voice of your beloved podcast host, and then they're like, “Buy this!”

You brought up artificial intelligence and ChatGPT, which is something worth talking about. ChatGPT was not on the scene when you were first writing Hum. I'm curious if you played around with it since. What your thoughts on AI writing? What do you tell your students about using GenAI in class?

My opinions about it are still evolving, but I would certainly never, as a writer, use ChatGPT, because writing is my favorite thing I do with my brain. Someone said to me recently she's trying to use ChatGPT to plan a family vacation. That seems like a good use of it. That's a potentially tedious project that ChatGPT could help you with. But for my very favorite thing to do, I'm not interested in outsourcing it. As an instructor, I am interested in my students developing their own voices, so I'm not interested in the voice that AI develops for them. I'm interested in their own process. So, I guess I'm pretty skeptical, but I do think that there are some good uses, like Jessica just said it's been really helpful with their invoicing here at Greenlight. That I approve of. And cancer research.

Hum is a book about technology and the near future, but it's also very much a book about a family. You have May and her husband and the two children as the main characters. How do you think technology and family in the book, and maybe in the real world are, coexist and how they're in friction with each other?

I'm glad you mentioned that it is a book about a family, because I feel like a lot of the talking points of the book are technology, artificial intelligence, climate change. But at base I hope it is a very human story about this family. There's a lot of talk about technology and how it's going to affect the future. As a parent, this is such a pressing everyday concern. How do you live alongside this strange guest in your home, which is the internet? And how do you deal with all the screens? And how do you teach your children to have a relationship with their own minds and their own creativity when there are so many distractions? Those are very pressing, concrete daily questions for me, so that definitely led to the book.

Another interesting area of friction in the book is the natural world and technology. The book is really seeded smartly with images of the natural world and food. I feel like food comes up a lot. That's contrasted with the cold, metallic hums and other technology. And then much of the plot of the book takes place in the Botanic Gardens. Or your version of Botanic Gardens, which is kind of like a nature preserve that only the rich can access, right?

That setting of a green space, a lush green space of nature in the middle of a city, came really early in the process. I think probably we can all relate to this as city dwellers, but it's so precious to have green spaces here. They just take on this sacred quality, whether it's Prospect Park or Fort Greene Park or Green-Wood Cemetery. I really wanted to try to evoke how incredible it is to have a green space in the middle of a city. And May longs for that. The place where she grew up has burned from forest fires. May is someone who is hungry for connection to her family, to nature, to herself, and she has this feeling that if she can get her family in this place that only rich people can enter, if she can find the way to get the money, which is by having this sick surgery she has, that maybe she will have some kind of resolution. That maybe she will feel like things are okay. But it really doesn't pan out that way. She's trying to escape. But I think one thing I'm trying to suggest in the book is that you can't escape. You actually have to confront things head on, like we would all like to run away into the pastoral wilderness, but we actually need to confront the realities.

Yes, it's very true. And then even in the even in Botanic Gardens, the artificiality intrudes, right? The children find some of the rocks are like plastic.

Yes, May has been enjoying the bird song in the garden and the sound of the wind, and then right as they’re leaving, she sees a huge disguised speaker. The bird song is flowing from a speaker. So, what is authentic?

One thing I always love in your writing is how you build tension, which in my reading is in part a shortening of paragraphs in the tensest moments. I was curious how much of that comes through in the editing. Is your editing process stripping away? Or does the prose come out that way?

It’s always stripping away. I find it really exciting when you overwrite a paragraph and then you take away from it, and suddenly the rhythm and the sound changes, and it goes down to its bones. That's what I always try to do for every sentence. But it is a sentence-by-sentence process. And again, I cut a ton--this book was literally twice as long as it is. Those paragraphs are arrived at by cutting a lot of dumb stuff that I put in the original.

You’ve mentioned Ted Chang and Ursula K. Le Guin as influences, and I always love to hear about influences. But I especially love to hear when writers talk about influences that aren't writers. Were there any films or music or any other kind of artistic mediums that you drew influence from?

Oh, that's an interesting question. I feel like one influence was going to parks in New York and going to Green-Wood Cemetery. Also there's a lot of music in the book. There's sort of a quality of sensory deprivation in the book. Like this world doesn't have a lot of vibrancy, and then music comes in at certain key moments. In my mind, I know what all of the songs are, though they aren't named in the book.

As a final question, I mentioned you said that you didn't want to write a “sheer dystopia,” and you wanted to have both some kind of complexity and maybe hope. Having written this book and researched a lot for it, I'm curious if anything in your writing or research has changed your relation to modern technology?

That's a good question. I do feel like I often write as an act of self-healing to some extent. Or an act of self-understanding. Like I said early on, a way of confronting the things that I'm frightened of. I should have mentioned in response to your last question that I conducted a few interviews. I talked to my friend Nora, who is a therapist, about robots potentially replacing therapists. Nora and I talk deeply about why that might not work. And I interviewed my colleague at Brooklyn College, Professor Ken Gould, who's a sociologist who studies climate change. I interviewed my friend Kendyl Salcito, whose nonprofit Nomogaia works on humans right impact assessment in different supply chains. I interviewed my friend Charlotte McCurdy, who makes sustainable fabrics out of algae. I'm mentioning all these interviews because I noticed a consistency emerging when I was talking to these people who are all engaged in the future in some way. I asked them, is there anything as you look at your field that gives you hope? And multiple people said community is the only way to do anything. You really have to have connection and community. That's the only way to make meaningful change. All these people in different disciplines, when I asked them that question, had such a similar answer. In the book, you maybe don't see that, although the hum casts itself towards that at some point that I won't reveal. But I’m thinking of the family as the original community and the couple as the original community from which that can spring. I was particularly thinking about that at the end of the book. At one point, May’s husband's phone dings in his pocket, and he doesn't pick it up, and he stays, he keeps his eye contact on her. In this world, it’s the height of romance to ignore your phone when you receive a text. So maybe start with ignoring your phone when someone's talking to you, and then we just will build out from there.

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.”

Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

Congratulations to Helen! I devoured this book in one day. It’s so deeply unsettling!

Looking forward to this, thanks for the interview. (Full disclosure: my story collection HUM came out in 2014 with FC2, so obviously, I love the title:)