Processing: How Ed Park Wrote Same Bed Different Dreams

The author on structure, humor, inventing history, and big ambitious novels

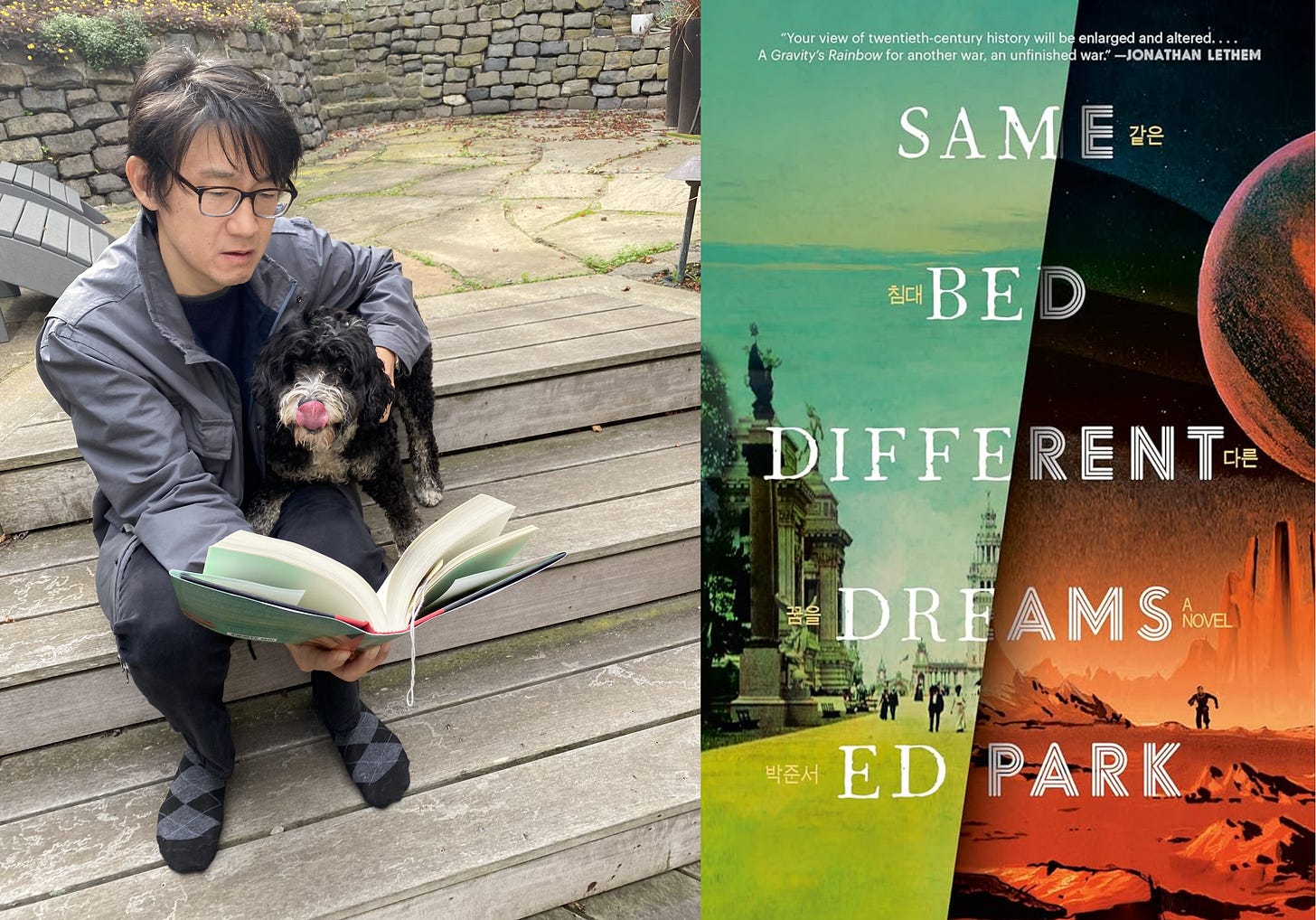

Last month, I wrote an article called “Why Your Novel Should Be More like Moby-Dick” that lamented the complaints about that novel’s “whale facts” chapters and talked more generally about how much I missed novels that were willing to be inventive with structure and form, go on long digressions, mix genres, and so forth. Novels can do anything, after all, so shouldn’t they try to? That night, after publishing the article, I went to a launch event for Ed Park’s Same Bed Different Dreams and discovered Park had just published exactly the kind of novel I’d been missing.

Same Bed Different Dreams is a comic genre-bending novel about Korean history, pop culture, struggling artists, secret organizations, tech companies, and really far more than I can fit into a summary. It’s strange, kaleidoscopic, and just a plain fun to read. (Here I must also recommend Park’s first novel, Personal Days, an office novel that is much shorter but equally unique and hilarious.) I reached out to Park over email for my semi-regular Processing interview series and we talked about structure, humor, and fictionalizing history.

Same Bed Different Dreams skillfully mixes multiple narrative threads, includes a novel within a novel, jumbles genres, and more. Can you talk about how you approached the novel structurally and formally? Did you always know it would be a novel where you would throw together lots of different elements and ideas?

I originally thought the novel would be in two parts—two “dreams”—consisting of Soon Sheen’s story, told more or less linearly, and a much shorter part done from a different character’s perspective. I wound up writing this two-parter, an ungainly first draft. It took several years to realize I needed to weave different voices and forms into the book, and that the structure had to be radically different. I threw out the second part of the original MS, and did a controlled demolition of the first part (now called “The Sins”) in order to accommodate two new storylines (“2333” and the “Dreams”), each with their own approach.

One of the (many) interesting elements of Same Bed Different Dreams is how you play with history. It is Borgesian in mixing very real Korean and other world history with invented and speculative history. How did you go about researching this novel?

In early 2019, it hit me that the novel-within-the-novel, which I’d only been alluding to, should (a) actually be written, and (b) should relate, in an entertaining way, a big chunk of modern Korean history. This interior book, written by a Korean novelist named Echo, is told as a numbered series of anecdotes, capsule biographies, historical facts, and wholly fictional ponderings—all of it the collective work of the Korean Provisional Government, a real-life independence movement formed in 1919 to protest Japan’s colonization of the country.

In my book, the KPG—in reality more symbolic than effective—lives on even after Japan leaves after World War II. Once I had this voice in mind, I felt free to bring in anything from all my years of reading about Korea and Koreans. So, I was already fascinated by figures like Syngman Rhee (first president of the KPG), Philip Jaisohn (exile turned American physician), and Yi Sang (avant-garde poet)—my research was more a way of going deeper into the lives of these figures. My mind was like a magnet, picking up stray thoughts that I’d had over the years, such as a quotation that’s lingered in my commonplace book for at least three decades: Jack London’s dismal view of Koreans, penned when he was a correspondent reporting on the Russo-Japanese War of 1904. Well, it’s been stuck in my mind for a reason; why not add him to the book? And what happens if you identify him as a member of the Korean Provisional Government?

The same thing happened with a “real fictional” figure named Taro Tsujimoto, a Japanese draft pick for the Buffalo Sabres who didn’t exist—I’d first written about him in 1994 (in a personal essay that was never published), and now I thought I’d include him in the book, except that he’d be real…It was that kind of thing—figuring out that one of my lifelong obsessions should be in the book, then reading more about that subject to fill in the gaps.

There’s an authorial stand-in, Soon Sheen, and the novel plays around with your own personal and family history too. How much fidelity to the real did you feel you had to have with either your personal history or global history?

Soon’s voice and situation came to me first—he’s the seed of the book. My initial burst of writing was that long first scene, “The Scourge of Seoul,” which is now chapter 2. That scene came to me up in Fishkill, New York, where I was spending a week alone, writing. I imagined what it would be like to live away from Manhattan, my home now for thirty years. Soon Sheen had some Ed Parkian characteristics: He was a Korean-Buffalonian who’d published a book years ago and who was wondering if he’d ever write one again. I also had worked in publishing and related fields, so the party guests populating the scene (a dinner party for an author named Echo) were like comic versions of myself—more talkative, profane, annoying than I generally am. Soon’s biography quickly detached from mine. He was a long-time employee at a tech company called GLOAT; he had one daughter instead of two sons; his wife was a nail salon tycoon.

When it comes to actual events (appearing mostly in the “Dreams”), I largely stuck to the historical record in terms of when people were born, where they were in any given month and year, what they were doing. I invented dialogue, of course, while trying to hew to what was known. For example, there’s a scene in which Punch Imlach, GM of the Sabres, is trying to woo his old Maple Leafs player Tim Horton (already a businessman) to join his new team. In Imlach’s memoir (written, by the way, with Neil Young’s father, a popular writer of hockey books), he recounts that Horton wanted a specific kind of car as a bonus. I had them meet at the original Tim Horton’s donut shop in Ontario, to get the deal points down—it was fun to imagine their conversation.

There is one character (I won’t say which) whose name popped up in my reading. So tantalizing and shadowy. I couldn’t find much information in English, so I asked my dad to do a rough translation of the more extensive Korean Wikipedia page. I used this as a scaffolding for that person’s life. It’s the most “invented” of the historical figures, which gave me pause; then again, I was already mixing purely fictional creations (the science-fiction writer Parker Jotter, e.g.) with real-life events. The novel can do what it wants.

SBDD asks, “What is history?” It’s the very first sentence, and it recurs throughout. The KPG asks the question, but I was asking myself the whole time. Now, finally, with the book out, I think the answer is the book itself, a blend of the real and the remembered and the imagined.

At your launch, I remember you saying you were inspired by big ambitious novels that tried to suck everything about the world inside them—you mentioned Infinite Jest and Pynchon I think. Can you talk about your influences and why you’re drawn to novels that try to bring in everything all at once?

In the mid to late 90s, as I was setting my course to be a novelist, some mind-bending tomes came out—chiefly, Gaddis’s A Frolic of His Own, DeLillo’s Underworld, Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon, and DFW’s Infinite Jest. I had already read everything DeLillo had written through Mao II, so in some ways Underworld was the big one for me. (Side note: I was an intern at Harper’s in 1992 as they were preparing to publish “Pafko at the Wall” as the first Harper’s “Folio,” and I became an instant fan for life.) These books were so brain-bending on every level—the language, the breadth of knowledge, the huge ambition…I don’t know if young writers still want to write that kind of maximalist fiction, but it felt like a worthy goal.

I should add that I was a student of the late Maureen Howard, whose books—from Natural History on—are extremely radical and voracious. Her final four books are a loosely knit tetralogy, with recurring characters but plenty of interludes and digressions and autobiographical patches breaking up any sense of linearity. She was a huge influence on me—she encouraged complexity, as long as the heartbeat of the story was strong.

Back to those big books for a second. I hadn’t read any Gaddis before Frolic, so I picked up The Recognitions (as well as A Reader’s Guide to The Recognitions!). It took me several years to get through the whole thing, which I liked. The talky, entertaining, chaotic party scenes in The Recognitions left an impression on me—indeed, in the original draft of SBDD, I included another massive party scene, introducing a whole new cast of characters. (I cut it later.) His books are so alive and funny, despite their sour view of human nature. You can get away with anything if it’s funny enough. There’s also the way certain figures weave their way through his books (JR is the other major one), sometimes disguised or misidentified in later appearances, which happens in my novel as well.

More recently—though I guess they’re old news now—David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas and Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Goon Squad excited me with their radical structural engineering. I can see now how the “2333” thread in Bed owes something to the way Egan’s novel moves through time, morphing in format with each chapter. (And “2333” is a nod to Bolaño’s 2666.) Books like these help stimulate the novel as an art form. [NB I’ll talk about humorous writing/influences later.]

Given the complexity of the narrative with its many characters and timelines, I’m curious how you kept track of everything. Did you outline? Have a corkboard of notes? Timeline spreadsheets?

I periodically typed out fresh outlines, catalogued characters, tracked activity—mostly on paper, sometimes on the computer. Then I’d proceed to ignore them. A month later, it would be time for a new outline, a new aspirational table of contents. This was my life for years. There are innumerable notebooks and shirt-cardboards and random scraps of paper with arrows pointing this way and that, phrases highlighted, utter visual madness.

I’m always curious about authors’ relation to genre, and I know you’re someone who reads and writes in different genre spaces. You’ve written noir fiction for the New Yorker, you used to write a science fiction review column, there are science fiction elements to Same Bed Different Dreams, Personal Days is an office novel, etc. How do you think about genre when writing fiction?

When it comes to stories, I’m thinking of voice more than genre, though often the piece drifts of its own accord into something gently science fictional or thrillerish. The novel I’m working on now is more explicitly aligned with horror, though it periodically drifts out of genre. I’m okay with that!

Same Bed Different Dreams is a comic novel that has quite literally made me laugh out loud on the subway. You’ve also written straight humor pieces before. Can you talk about your approach to humor? Did you ever want to be a stand-up or comedy writer?

As a youngster, I was an avid bleary-eyed watcher of Late Night With David Letterman, a fan of Monty Python and Douglas Adams’s Hitchiker’s Guide books (well, the first two), and a consumer of Vonnegut and Brautigan. Newspapers were very much a thing, and I was devoted to the comics page and to Dave Barry’s column. (Come to think of it, I edited the humor pages in both my high school and college newspapers, and I wanted to be a cartoonist at one point.)

Discovering Charles Portis (The Dog of the South) and Anthony Powell (Afternoon Men) in my twenties helped spark my interest in writing a pure comic novel, resulting in Personal Days. For Same Bed Different Dreams, I tried to organize the “Sins” storyline around comic set pieces—a dinner party ending with a drinking game, a dialogue-only bedroom scene, a series of phone conversations with people who want something from Soon, etc. And there are comic stretches in the other two threads as well.

The big challenge to writing humorous fiction is that once you start revising, the jokes have to still be funny not just on the second read, but on the seventeenth and the seventieth.

Lastly, any advice you’d impart to a novelist reading this interview who is struggling with their own sprawling, ambitious manuscript?

Embrace the sprawl! And make sure you back up your files.

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.”

Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

Sounds amazing! Definitely have to pick it up ... After reading Milorad Pavic Dictionary of the Khazars, I bumped into the fascinating real figure Claude Bragdon; a Rochester-based architect and spiritualist who wrote this wild little book called a Primer of Higher Space in which he deconstructs the tesseract and the mathematics behind the 'Magic Cube' to prove the existence of the afterlife. For years, I noodled around with an idea for a book that was going to be 81 super short chapters that would cross narratives like Bragdon's cube and Pavic's hyperlinked Dictionary. I ended up adapting some of those pieces for the story within a story (within a story) novel I'm just finishing now for my MFA at St Francis, but maybe some day I'll go back to that idea. Loving the sound of Same Bed ... thanks!

Yay for another Ed Park novel!