Your Novel Should Be More Like Moby-Dick

Why not put some whale facts chapters in your WIP?

Moby-Dick resurfaced in the discourse this week, and whenever Melville’s leviathan breaches the timeline there are complaints that the novel is ruined by chapters of “whale facts” that “distract from the plot.” Seeing these grumbles again made me think about, whew, I wish there were more whale facts in contemporary novels!

The whale fact chapters in Moby-Dick are among the most memorable parts of the book. (Which, if you haven’t read, is far funnier, weirder, and gripping than you likely imagine.) Of course, the “whale facts” chapters aren’t just about facts about whales. Moby-Dick includes weird and philosophical digressions about many subjects, such as the meaning of the color white, as well as chapters in the form of plays. Melville is always mixing it up. Moby-Dick might have a narrow central subject, but it is expansive in scope and Melville always seems hungry to try something new, shift moods, or follow thoughts where they take him.

And why shouldn’t we mix it up? Why shouldn’t writers follow their obsessions and interests and strange ideas? The result is almost always going to be more memorable than an unthinking devotion to plot beats and character arcs.

As common as it is to say that anything that doesn’t move the plot forward is “unnecessary” or “getting in the way,” the argument is silly. What book could even last 10 pages if all description, interiority, digression, atmosphere, and other literary pleasures were stripped away to leave us only with “necessary” plot beats? Just read a Wikipedia plot summary if that’s what you’re after.

The obsession with plot movement rendered through televisual scenes at the expense of other pleasures seems a very modern and very American attitude. I have to imagine much of it comes from the domination of Hollywood in American culture, which has passed down many “rules” of storytelling to other mediums. While I don’t necessarily agree with those rules for filmmaking anyway, they’re bizarre to apply to novels. Many of the film and TV rules for storytelling have to do with the basic constraints of filmmaking. Primarily, it costs a lot of money. And film is a visual medium where story is conveyed by actors moving and talking. But novels are not bound by production costs, fitting in commercial breaks, or the need to convey story only through actors’ actions and dialogue.

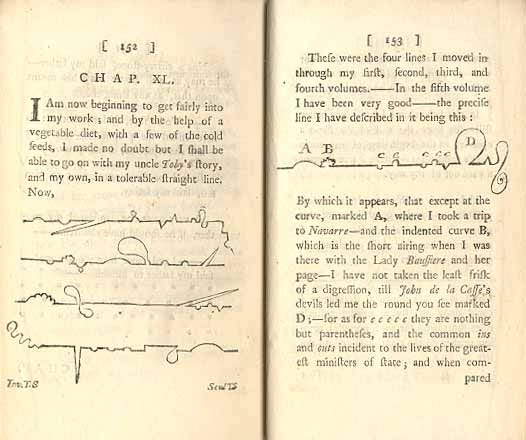

A novel should lean into the pleasures and possibilities of a novel, I say. The novel is an explosive, expansive, and exuberant form. It can encompass anything. Certainly early novels like Don Quixote and Tristram Shandy knew this, as did modernists like James Joyce and Virginia Woolf. Such writers leaned into the varied possibilities of fiction and were always willing, even eager, to shift form and style.

Indeed, it is often the unique parts of these books—the parts that swerve and transform the narrative—that we remember best. What would Tristam Shandy be without the diagrams or To the Lighthouse without “Time Passes”? And, yes, what would Moby-Dick be without the digressions? Publishers have stripped them out and the result isn’t an improvement. Adam Gopnick in the New Yorker reviewing one abridged version: “it turns a hysterical, half-mad masterpiece into a sound, sane book.”

Who prefers sound and sane over hysterical and half-mad? I doubt Moby-Dick would have endured to today if it was merely sound and sane.

Of course, I don’t mean to act like this spirit is gone from fiction. You can see it in Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, Lucy Ellmann’s Ducks, Newburyport, or Percival Everett’s Erasure—recently adapted as American Fiction—which includes a parody novel in the middle of the main narrative.

Surely there are novels that thrive on tightly-paced action and mounting tension that might be ruined by a shift in style or a long digression. Some novels do work best as a string of taut televisual scenes without interruption. But that’s hardly every novel.

Outside of the Hollywood influence, sometimes writing professors or critics will explain that it’s imperative not to include “whale facts”-type chapters or switch form or POV on the page because it breaks the fictive dream. Readers want to get lost in a narrative and anything that distracts from the immersive experience will ruin the spell. At least that’s the argument. Frankly, I’m not sure this was every true of how people read. But I really don’t think it’s the case in the modern age when novels are read between cell phone scrolling and myriad other tasks. Very few of us sit down and read a novel in one sitting in our cigar-smoke-filled study without distraction. We are exiting and entering the fictive dream at rapid pace. Switching up form and style won’t change that. Hell, maybe it will keep the reader’s attention?

(For what it’s worth, I’m very much trying to practice what I preach and bring this spirit to my next novel.)

Many of my favorite novels lean fully into unusual forms. Nabokov’s Pale Fire is a novel written as scholarly notes on a poem. Zambra’s Multiple Choice takes the form of the Chilean Academic Aptitude Test (similar to the SAT). Robison’s Why Did I Ever is a novel in fragments. Etc. But I don’t think such formal playfulness must be restricted to books that follow them fully. There’s no reason you can’t, like Melville, insert a chapter in the form of a play or a digression about whales facts into your otherwise traditional narrative. Of course, what “whale facts” are in your book likely won’t have anything to do with whales. Maybe it’s a list of physical injuries your character has suffered. Or a chapter in the form of a text message exchange. Or an illustration appearing suddenly in the middle of the book. Who knows? But you’ll only find out if if you’re willing to mix it up.

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.”

Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

I totally agree, but literary agents seem to run from such discursive novels like the plague. Ask me how I know.

I'm fresh from a rejection due to whale facts-type reasons, so this was exactly what I needed to read today. Thank you.

The book might seem like it would work better without the whale facts, but it doesn't. It goes bland. Just need to find the person who sees that.