We like to pretend that art is art. That an author writes what they are inspired to write, with no concern but the voice of the muse. This is a useful fiction. It is good for writers to focus on the art when writing and worry about the business side later. But it is a fiction. Writers are aware of market demands, what kinds of novels get buzz, and what subjects award judges gravitate towards. Even writers with high artistic aspirations are—consciously or unconsciously—warped by these pressures. Especially those of us hoping to make a living on our writing.

In my recent post on the literary fiction and SFF short story markets, I mentioned how the short story was the economically dominant length of fiction in the first half of the 20th century. Writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald bemoaned the fact they had to write short stories to subsidize their novel writing. In 2021—and really the last 50 years or more—the dynamic has been the opposite. Today, short story writers frequently (if mostly privately) grumble about how they have to write novels if they want any chance at earning money or even just getting an agent.

This got me thinking about one of those rarely-spoken-about-but-interesting-to-me topics: what determines the lengths of novels?

The novel is an extremely flexible form. It can come out in countless shapes, include infinite content, and end up almost any length. Let’s call the lower limit of a novel 40,000 words. Long novels like Infinite Jest and The Stand are more than 10 times that length, and that’s not even getting into series or In Search of Lost Times type works that are published in dozens or more volumes. So why are most novels published in a relatively narrow range of 60k to 120k words?

Or to put it another way: why doesn’t anyone publish novellas in America? Novellas as a form thrive in many parts of the world. They’re very popular in Latin America and Korea, and hardly uncommon in Europe. Yet it’s almost impossible to find a book labeled “a novella” in America outside of small press translations or classics imprints.

Historic Novel Fluctuations

The length of books is one of those things that varies from genre to genre as well as era to era. Take high fantasy, a genre famous for its massive tomes ever since Tolkien. Even those tomes have grown longer as the decades have passed. The last individual volume of George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series has close to the same wordcount (422k) as all three volumes of Lord of the Rings combined (480k)! There’s been similar bloat in children’s fantasy. The Narnia books were all 39k to 64k in length, novellas to short novel range. Compare that to the volumes of His Dark Materials (109-168k per volume) and Harry Potter (74k-257k).

In general, popular genre fiction—thrillers, mysteries, etc.—and commercial fiction tends to be longer than so-called literary fiction these days, although all genres of novels became more bloated in the second half of the 20th century. Then again, pre-20th century novels were often quite long. Charles Dickens novels like Great Expectations (183k) and Bleak House (360k) or Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility (126k) or Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (183k) and other novels of that era were frequently tomes by even today’s standards.

So what explains these novel fluctuations? One obvious factor for the length of 19th century English novels is that they were typically serialized either in magazines or else as a series of pamphlets. The more you wrote, the more you were paid. Pretty simple. The economic pressure was to write long works. Serialization of course also changes the content of the novel, not just the length, as you need to have cliffhangers and hooks at the end of each installment that will keep the reader coming back. Art is never free of economics in capitalism.

When we get to the early 20th century in America, the economics of publishing shift toward the newsstand. On newsstands, space matters. Neither the magazines themselves, nor the content inside, can take up too much valuable real estate. Pulp magazines dominated, and short stories become the smartest way to make a living. When it comes to novels published by publishing houses, 20th-century writers are getting paid per book instead of per word. Publishing houses put out a single unit, not serial installments. The advance on a 170k novel is not necessarily more than the advance offered on a 70k novel. There is far less economic incentive to write long Victorian tomes. Indeed, it makes a lot more financial sense to split a 170k novel into three short books and call it a series especially if you are writing to a reliable fan base. And so from this point you see novel series really begin to dominate SFF, crime fiction, and other genres—though not really literary fiction—a trend that’s still pretty true today.

If the late 19th-century offered economic incentives toward long novels and the early 20th-century created different incentives for shorter works, what explains the bloat of the second half of the 20th-century?

One culprit I’ve heard named is grocery chains.

Americans Buy in Bulk

Americans expect bang for their buck. Yet the price of novels is unrelated to length. Trade paperbacks are around 16 bucks a piece whether they are a 100-page novella or a 400-page tome. Even among highbrow literary readers, I’ve heard people say they rather get a long book than a short one for the same money. Why pay the same for 2 hours of entertainment when you can get 10 hours of entertainment for the same price?

Years ago I read a post by the SFF author Charles Stross about how grocery stores specifically drove this bloat in novels:

One account I've heard (from an editor who was active throughout this period) is that it was the distributors. The mass market for paperbacks prior to 1991 was dominated by wholesalers who supplied retail stores — not bookshops, but local supermarkets with wire-mesh book racks. The wholesalers knew their markets intimately, and would match mass-market titles to the supermarket customers on the basis of their clientelle — SF/F was popular near technical schools, for example. When the inflation of the 1970s and 1980s forced publishers to raise their cover prices, the distributors pushed back and demanded that if the product cost more, it had to be bigger — not taller or wider, else it wouldn't fit the racks, but fatter. (They were, after all, primarily in the grocery business rather than the book trade. You want to charge more for that lettuce? It better be bigger!)

This explanation seems plausible to me, even if it is depressing to think that something as arbitrary as wire racks in grocery stories could change how novels are written. As Stross says “from the 1960s to the 1990s, publishers unconsciously trained readers to expect longer novels” and even books more likely to win Pulitzers than be on a grocery store rack started to get longer.

Although I do wonder how much grocery stories played a role outside of commercial fiction. Even readers that never bought a book in a grocery store in their life started to gravitate toward longer books. I wonder if Americans are just trained to think this way in everything, at least were trained to do so in the Yuppie 80s and booming 90s. The grocery store just lays that bare.

Why Not Charge Less for Shorter Books?

One might think that readers expecting bang for the buck would mean that publishers should vary their book prices more. That way, any length of novel could sell just as well. Every now and then, a publisher will issue a series of very short books or novellas but still charge close to the same price as a trade paperback. As a reader, I gravitate toward short books. But even though I try to actively resist the idea that art can be bought by the pound, I can’t deny I hesitate at paying $13 for a 90 page book when I could pay $16 for a 400 page one.

Yet from the publisher’s side, it doesn’t make sense to charge much less. The problem is that the actual cost of paper is marginal. The price of a book has very little to do with the physical materials of the book. (This is a something the “ebooks should be super cheap because they’re free to make!!!” crowd completely ignores.) The actual cost of a book is wrapped up primarily in a) distribution and b) retail mark up. That’s the majority of the price of a book. After that, of course, you have the author’s cut, cover art, editing, layout, and so on, all of which cost just as much for a 100-page book as a 400-page tome.

Prestige Pressure

Money isn’t the only pressure on authors of course. Prestige can matter just as much. Novels are more widely covered in the media and (in literary fiction especially) are far more likely to win awards. Even if you’re writing experimental fiction that will never earn a lot of money, there’s prestige pressure to write novels over shorter forms.

There’s also a sense that epic tomes are more likely to win awards than tight, short novels. I’ve never seen data on this, but it’s something writers talk and think about. The feeling exists. As if literary judges “buy in bulk” just as much as readers, thinking that the longer something is the more it must have to say. When I think of award winners, I think of huge books like All the Light We Cannot See or The Goldfinch and never a slim little novella. When a writer put out a big old book for their third or fourth novel, there’s a sense they’re taking their big swing at a Pulitzer.

I should say that many writers also feel this way: that longer books are more important. I can’t count how many times I’ve seen this quote from Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 quoted on social media:

What a sad paradox, thought Amalfitano. Now even bookish pharmacists are afraid to take on the great, imperfect, torrential works, books that blaze a path into the unknown. They choose the perfect exercises of the great masters. Or what amounts to the same thing: they want to watch the great masters spar, but they have no interest in real combat, when the great masters struggle against that something, that something that terrifies us all, that something that cows us and spurs us on, amid blood and mortal wounds and stench.

(The irony is Bolaño’s novellas—especially Distant Star and By Night in Chile—are his best works!)

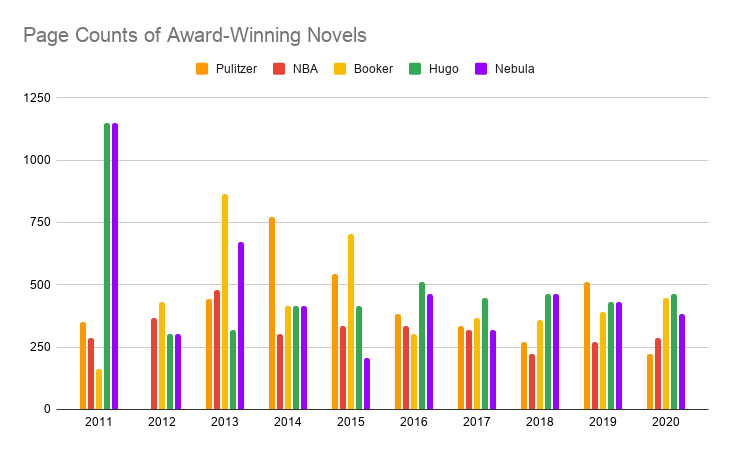

Since I’ve never actually seen data on the length of award winners, I wasted a bit of the morning looking up the last ten years of big award winners. I used page count instead of word count, since, to be blunt, that was easy to look up online.

Three quick notes on this chart. In 2012, the Pulitzer board refused to pick a winner from the finalists (justice for Train Dreams!). In 2019, the Booker co-awarded Bernardine Evaristo and Margaret Atwood so I averaged their page lengths. The 2011 Nebula and Hugo winner was Blackout / All Clear by Connie Willis, a single novel published as two books of 491 and 656 pages individually. Since the two were awarded as one book, I’ve combined the page count.

To be honest, I expected the page counts to be a bit more bloated than they are. Although the average (mean) for each award was in the tome territory of low 400s for the lit awards and high 400s for the SFF awards, excepting the NBA which came in at a longish-but-not-a-tome average of 321 pages.

The chart does add a data point to the anecdotal evidence that SFF books tend to be longer than literary fiction ones. Although the average (mean) lengths weren’t that different, there is far more variation of length in the lit awards including many shorter books below 300 pages. Between the Hugo and Nebula, only one book—Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation—is under 300 pages versus seven from the three lit world prizes. The median lit award novel was 336 pages vs. 432 pages for the SFF awards.

Ebooks and the Future of Novel Lengths

If novels were long in the late 19th century, short in the early 20th century, and long again in the late 20th century… does that mean we’re due for a contraction?

Well, maybe. A funny thing happened on the way to the ebook revolution: books got shorter again. Well mostly the ebook revolution didn’t really happen. Print books still dominate the market, a fact that would utterly shock many people who as recently as 2015 had convinced themselves print books were about to be as rare as VHS tapes or CDs.

But ebooks are still a part of the market and there’s a whole, almost separate, ebook ecosystem for self-published authors. As digital files, there are no issues of binding, shelf space, or shipping to restrict length. One might think that ebooks would encourage even longer novels. Instead, in the ebook market short books started to dominate to the degree that self-published authors publish a single average length novel as multiple “books” and call it a “series.” Many self-published “novels” are barely longer than a short story. Then when an author makes the jump to the print market, they often publish the “series” as a single novel. For example, Wool by Hugh Howey was originally sold as several books before being grouped as one print novel.

The reason for this is, yes, economic. The model that seems to work best for the self-published ebook market is providing a very cheap or free first entry, then once the reader is hooked charge them again and again for the rest of the story. Basically, the ebook market has returned to the Victorian serial model.

I would also hazard to guess that the “buy in bulk” American mentality fades when you can’t physically see the size or something. An ereader will note with little dots or lines how long different files are, but it doesn’t have the same impact as visually seeing a gigantic book next to a tiny one.

But maybe print books are getting shorter too?

The Secret Novellas of American Fiction

If you got to an American bookstore and look at the front tables of new books, its unlikely that you’ll find a single “novella” by an American author. Although in other countries novellas are so common that popular writers like César Aira seem to publish almost exclusively in the form, the word scares off American readers. (Although it is worth noting that the SFF world is more receptive to novellas than other genres.) When novellas are published by American authors, they tend to be added at the end of a collection of short stories such as George Saunders’s CivilWarLand in Bad Decline or Danielle Evans’s The Office of Historical Corrections—to pick two excellent “stories and a novella” collections.

Yet this isn’t entirely true. In recent years, short novels have become more and more common. Some acclaimed literary books are as short as 50k or 40k or even under 30k(!). These books simply aren’t called novellas because the American reader wrinkles their nose at the term.

Remember when you were in high school and stretched out your margins, line-spacing, and font to try and make your three-page paper look like a five-page one? Well, American publishers can pull a similar trick. Margins, font, and trim size can all be manipulated to make a book look longer or shorter.

Here’s an example: Samanta Schweblin’s Fever Dream—one of my absolute favorite books of the last decade—clocks in at under 28k words. Solid novella territory despite the “a novel” on the front cover. However, the layout and small trim size stretched it to 192 pages. For comparison sake, The Great Gatsby is 180 pages in the Scribner edition and is 47k words plus an introduction. Fever Dream (which again is fantastic please read it!) is of course translated. But I see more and more American-authored books published in the 25-45k wordcount range.

I want to be clear and say this isn’t a bad thing in my view! I’m a lover of short novels and novellas so whatever gets them to market is good in my book.

Art Is Still Art

I find the always fluctuating history of these forms fascinating, and the economic pressures worth talking about. But of course, art does have its own power. Books do tend to end up the length they want to be. As writers, we can choose to devote times to projects that seem more likely to be published or bring in income. We can work on that novel draft instead of short stories, or that book we think is an award contender rather than the one that’s too experimental to get published. But an individual work of fiction has its own desires and demands.

As a lover of short novels, I’ve always aimed to write trim ~60k novels. Yet all three of the novels I’ve finished—including my pre-orderable science fiction novel The Body Scout!—have ended up in the 80-100k range. Truly despite my best efforts. Hopefully one day I’ll manage to write a slim little novella, which someone will publish as a novel, and shower with awards and money. Amen.

My experiences as a bookseller over a couple of decades would tend to suggest the genre keeping the lights on in the bookstore the most (romance, which you don't mention) has had a readership long happy to enjoy shorter-length works. Or at least, there doesn't tend to be as many much-larger-length works as in SF, for sure. Category romance also tends to shift to the shorter side, be it 200 pages/55k words or so.

Similarly, romance novellas—especially in the age of e-readers—have had an up-tick, especially among queer and/or BIPOC narratives. It feels like the genre itself can often lend itself to a shorter/tighter narrative (the holiday novella boom alone every year come winter is kind of amazing to watch).

Interesting, and I'm in agreement. One quibble, though: it's not true that "...editing, layout..." costs are the same over 100 pages as over 400. I speak as a guy who's designed about three dozen books (for small presses) and I charge more to design a 400 pager than a 100 pager -- because it takes me much longer. And the editors I know would agree, too. None of this takes away from the thrust of this excellent posting.