A Long Post about Short Stories (and Magazines)

Part III of a series on the literary fiction and SFF ecosystems

Publishing runs on novels. At least when it comes to fiction, novels are what agents want to hear about, what editors want to look at, and—with a few exceptions—what readers want to buy. Perhaps because of this, short stories hold a special place in fiction writers’ hearts. The short story is our form. Our weird mysterious little monster that no one else can love.

Strangely, the opposite was true 100 years ago. For the first few decades of the 20th-century, the short story was the popular form of literature. It was a magazine world back then. Short stories were what paid the bills. Authors like F. Scott Fitzgerald felt forced to write short stories that they could afford to write “decent books” (novels) on the side! In the genre world, the short story was so dominant that even the “novels” were often a bunch of existing short stories stitched quickly together in what was known as a “fix-up.” I’m not talking obscure books here, but some of the pillars of SFF from that era: Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles, Asimov’s I, Robot, and Simak’s City. Also several of Raymond Chandler’s best hardboiled novels over in crime fiction. (Here’s a good post by Charlie Jane Anders arguing the fix-up is the ideal form for SFF.)

Anyway, at some point the mass market paperback was invented, magazine readership declined, and the novel—that great baggy lumbering beast—took over. Paradise (for short story writers at least) was lost. Still, short stories remain an extremely vital part of the writing ecosystem. Short stories are where writers test themselves, gain name recognition, and build up an audience. Writing workshops, whether MFA or Clarion, are focused almost entirely on short stories. They’re the form you study, imitate, and submit to class. This is mostly for rather practical reasons: they’re shorter, so take less time to read and talk about. But it is still the case.

So short stories and the magazines that publish them seemed like an ideal topic for the third entry on this little newsletter series on the difference between the literary fiction and SFF ecosystems. The first post was on the different jargons of the literary and SFF worlds and the second was on awards and prizes (if you missed them before). The quick caveat is that I’m an author who writes, and publish in, both “literary fiction” and SFF about equally. This series is investigating the differences in how the two—still very separate—ecosystems operate, not “picking a side” between them.

Short stories and lit mags are also the world I know best. I’ve been publishing stories for many years, and have edited at many literary magazines as well as co-edited a series of short story anthologies that explicitly looked to bridge the divide between genre and literary fiction. So this is a topic dear to my heart… and this post may go a bit long!

Ray Guns and Page Two Flashbacks

Magazines are one of those areas where the genre and literary worlds rarely overlap. SFF and literary imprints are often owned by the same parent company, and literary agents often represent a range of clients, but the magazines are independent entities that evolved with different rules and features. Success in one doesn’t foretell success in the other. I’ve talked privately with several well-published SFF authors who have never been able to crack the lit mag markets, and I’ve known many well-published literary authors who have been failing for years to get a single SFF magazine sale.

Before I delve into the more substantive differences, here are some more superficial differences that are perhaps anthropologically interesting:

“Mag” or “zine”: For some reason the word “magazine” has been shortened to “mags” in the lit world and “zines” in the SFF world. I’ve never once heard anyone refer to “lit zines,” yet in the SFF world “zine” is an official term. For example, awards like the Hugos have categories for “Best Semiprozine” and “Best Fanzine.”

Submission system: Most lit mags use the Submittable online submission system, while most SFF zines use Moksha.

Formatting: Lit mags tend not to have specific formatting requirements—beyond basics like double spacing and a readable font—while the genre mags frequently refer to “standard manuscript formatting,” which is a bizarrely (in my view) specific formatting requirement. Genre mags might say they’ll reject a story that isn’t in this format off the bat and so if you’re crossover writer you should plan to format all your stories twice.

Payment: SFF magazines pay per word rates while lit mags (when they do pay) typically have a set “honorarium.”

Submission rules: Almost every lit mag allows for “simultaneous submissions”—submitting to many magazines at once—while most genre magazines don’t. (Perhaps this is because literary magazines take months or even years to respond while genre magazines are much quicker.) On the other hand, virtually no lit mag accepts “previously published work” while many big SFF magazines will consider “reprints,” typically for a smaller payment.

What do you want??: Lit mags are typically vague about what work they want. “Send us your best work” is the standard line. This isn’t mere bullshit. Lit mags do tend to publish an extremely broad range of work. Even at the biggest magazines you might find a magical realist story next to domestic realism beside postmodernist flash fiction (with poetry, criticism, and essays mixed in). Genre magazines are a little more specific, at least narrowing it down to broad genres. For example, Lightspeed takes “science fiction and fantasy” while their sister magazine Nightmare takes “horror and dark fantasy.” Genre magazines are often even more specific, giving you a list of what they are looking for or—in the case of Clarkesworld—a long list of stuff they do not want (the following is just the start of the list):

Those are some mostly quirky differences. There are more significant ones I’ll dive into below. But perhaps first it is best to give a quick snapshot of the two magazine ecosystems.

The Lit Mag World:

The lit mag world is a wild publishing jungle. New magazines pop up and wither like weeds each year. Walking down the endless lit mag tables at AWP is dizzying. Chaos reigns. There is nothing at all resembling official standards that anyone adheres to—a marked difference from the SFF world—which results in both a lot of vibrant and unique magazines as well as a lot of extremely unprofessional behavior. Magazines might get back to you in six weeks or six months or longer. A couple big magazines are famous for years-long wait times!

You could probably group lit mags into four big groups:

The glossies: These are general magazines that include some fiction and/or poetry. They are run professionally, pay very very well, and have large circulations. This used to be a long list, but at this point is mostly The New Yorker and Harper’s. Some other glossy magazines like The Atlantic, Playboy, Esquire, and O, The Oprah Magazine also publish fiction, but it’s inconsistent from year to year. The New York Times, BuzzFeed, and other national newspapers or websites also sometimes publish literary fiction and/or excerpts.

The established mags: Next you have the big famous lit mags. The Paris Review, Granta, McSweeney’s, One Story, etc. These also pay well and are run professionally. They are often non-profits, have boards, and are funded in part by grants. They might host writing conferences or awards. Several have book imprints. There are also some general culture magazines that aren’t glossies I’d include here like BOMB and N+1.

The university mags: A huge number of literary magazines are affiliated with universities, typically connected to MFA programs or undergraduate creative writing programs. Pay varies wildly. Sometimes it’s a lot, but frequently it’s nothing. Editorial staff is likely partly or entirely students, and so changes each semester or year. Although some famous ones have established university-paid editors. These run the range from excellent award-winning lit mags like Ploughshares (Emerson) and VQR (UVA) to tiny magazines few have heard of and even fewer read.

The independents: Lastly, but in no way least, you have all the independently run magazines. There’s a great vibrancy here with lots of unique magazine concepts or specific aesthetic visions. Some of these magazines, like NOON, are also among the most award-winning and acclaimed magazines around. Others are a website that popped up last week. These magazines might be a few friends publishing out of pocket—this was the case with the magazine I co-founded, Gigantic—or be funded by a wealthy person who cares about the arts. Or they might be something else entirely. They might have a real staff or just be one person and a few volunteers. Really, anything goes in the lit mag world.

How many lit mags exist? Who the hell knows. Clifford Garstang’s Pushcart Prize Ranking lists over 200 literary magazines that have gotten at least one “special mention” or award from the Pushcart in the last decade. A few of those are defunct now, and then there are undoubtedly many others that have never been awarded by the Pushcart.

The SFF Zine World:

The SFF magazine world is also a vibrant scene with many interesting magazines. But because it has official standards—set by organizations like SFWA—things are less all over the place than the lit world. When you submit to a SFF magazine you are (normally) not going to wait a year or more to hear a response. And you will almost always get paid.

Like the lit mag ecosystem, there are some glossy magazines or popular websites that sometimes publish SFF—Slate has had an excellent “Future Tense Fiction” series for the past few years and Vice’s SF online magazine Terraform is fantastic—although there’s no equivalent to The New Yorker here in terms of consistent publication and huge circulation.

Overall, the SFF magazine world is smaller. Locus’s 2020 magazine summary counted 81 magazines. Let’s break them down:

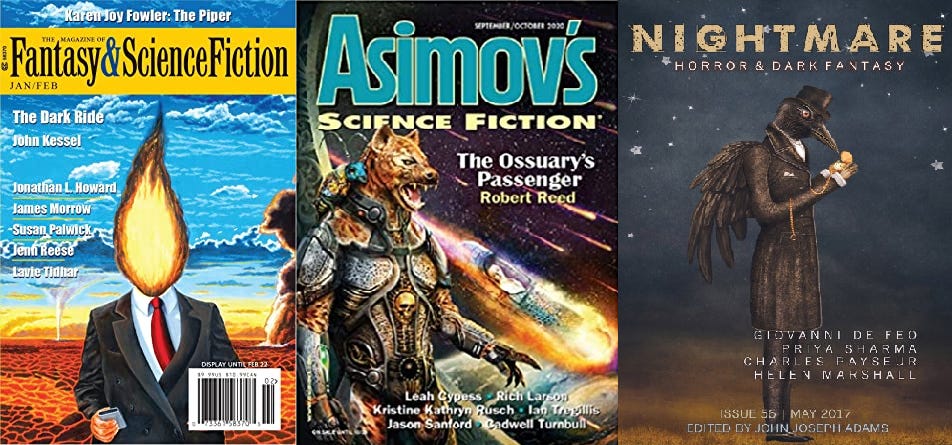

The Prozines: Locus counts 15 SFF professional magazines. These include the long-running pillars Analog, F&SF, and Asimov’s Science Fiction as well as more recent and justly acclaimed magazines like Lightspeed, Nightmare, Fantasy, Clarkesworld, and Tor.com. The pay rate is between .06 and .25 cents a word with an average of about .09 cents.

The Semiprozines: Many of these are magazines that by lit world standards would be considered huge and professional. They pay their writers and staff and publish regularly. These include frequent Hugo Awards contenders Uncanny, Strange Horizons, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Fireside, and FIYAH, as well as more obscure magazines. The ones I listed tend to pay about the same as the prozines, but smaller SFF prozines might pay .01 cent a word or less.

Podcasts/Audio Mags: The Locus overview also includes a couple audio magazines, like Escape Pod, some of which pay decent rates. There is nothing like this that I’m aware of in the lit mag world. Some lit mags release podcasts or audio recordings of published work, but they are not primarily audio magazines.

The Fanzines: These are “loss-making hobbyist pursuits” (as defined by the Hugo) and while many might be interesting, they don’t tend to appear on a SFF author’s radar in terms of submitting and publishing short stories. (This contrasts with the lit world, where very small and new lit mags can win awards and notice for authors.)

Professionalism, Contracts, and Money

As evidenced by the summaries above, the genre world is far more focused on professionalism than the literary world, which prides itself more on community. I just last month got two stories accepted in two of the biggest SFF prozines—after frankly years of mostly form rejections—and the emails illustrated this perfectly. The first magazine sent me a contract along with the acceptance and paid me one business day later. The second magazine apologized for not sending a contract right away… because they were in the process of getting contract revisions approved by the SFWA.

From someone more steeped in the lit world, these blew me away. It’s unfathomable to think of a literary magazine waiting for, oh, the Author’s Guild or AWP to approve contract language! Lit mags also typically pay on publication, or perhaps months later, if they pay at all. Their contracts are all over the place. Often there are no contracts at all. (FWIW, I’ve never had a crooked rights-grabbing contract from a lit mag like I have from big newspapers and/or general interest websites. The literary world just doesn’t have the equivalent of something like the SFWA guiding policies.)

The SFWA—and similar organizations in other genres—help determine what is considered professional, which has consequences for authors. What is eligible for different awards, or who can become a SFWA member. In SFF, magazines pay different per word rates and a low rate can cause backlash and scandal. Lit mags that do pay typically offer what they call an “honorarium” and the exact payments aren’t always listed publicly.

Contrary to what many genre world people think, this doesn’t mean that genre magazines necessarily pay better. Indeed, if we’re counting magazines like The New Yorker and Harper’s then the big literary magazines certainly pay more. Even discounting those, there are many lit mags will pay more for a 4,000-word story than $320 dollars (4k x 0.08 cents, the current “professional” standard). The differences are that all the SFF magazines pay something and that prestige is tied to pay. In the lit world, many celebrated and award-winning lit mags pay noting but contributor copies. Publishing big names, winning awards, and fostering community does more for lit mag prestige than pay most of the time.

The different focuses bleed into how authors talk. SFF writers will talk about “selling” stories to “markets.” “I’ve got four sales to professional markets, and five to semipro markets this year.” No one in the lit world would ever talk this way. The lit world—for better or worse—considers talking about money crass. You would say you “got a story accepted to a big mag” perhaps, but never “sold to a pro market.”

In general, I must say I find the genre world’s emphasis on standards and professionalism refreshing. That said, I do sometimes think it goes overboard. It’s great that every SFF magazine pays, but when at the lower end that pay only amounts to say 20 bucks a short story, is it really worth fussing over? It would be great if every university-affiliated magazine paid. The established ones and glossies already do. But when it comes to independent lit mags, most are run by other writers who are likely losing money on the venture anyway. If not paying writers—again on a magazine that doesn’t make any money—means that some cool, weird, and interesting magazines can publish that seems like a fair trade to me.

Links and Resources

Okay, I think I’ve written plenty here! This should give you good overview of the two worlds. As always, I hope we’re moving to a future where authors can move more freely between these different worlds. And it does seem to be happening more and more. Cross-pollination produces the most exciting work. If you’re a writer looking to publish in one, the other, or both of these worlds here are some resources:

Lit mags:

· Years ago I wrote this guide to lit mag submissions and I think the advice still holds up.

· Garstang’s Pushcart Prize ranking is a great place to find lit mags to submit to. Don’t overthink the exact ranking placement, but any of the magazines in the top 100 or so are worth investigating. (And plenty below that are too.)

· Jon Fox has a similar ranking based on the Best American series.

SFF:

· Locus’s magazine list includes most of the SFF mags you’ll want to look into.

· Jason Sanford’s “stage of the genre” mags post gives a good overview of things (also reminded me of the Fitzgerald anecdote).

· The SFWA membership rules also lists what they consider qualifying SFF markets.

My own personal advice is read a lot of lit mags, cast your submission net widely, read the guidelines, and format all your crossover stories twice. Seriously, the genre mags love that “standard manuscript formatting.” And don’t self-censor. Don’t be afraid to send weird work to both lit and SFF mags. In my experience, you truly don’t know where a story might land until you try.