More Publishing Facts You May Not Know

Explaining some myths about publishing, books sales, and author advances

The past few weeks have been fun for the handful of us nerds who enjoy chatting about the ins-and-outs of publishing. Or maybe it’s many handfuls, as my contribution to the discourse—started by Elle Griffin’s viral article “No one buys books”—has quickly become one of my most read posts. The readers yearn for the book data mines!

There were many other worthwhile reads on this topic here on Substack.

wrote about some of the things publishers do for writers. discussed how publishing makes authors feel like losers and the “status resentment” of contemporary American culture. asked everyone to stop mindlessly bashing book publishing. explained the ways publishing is actually thriving. I’m sure I’ve missed a bunch. Feel free to post any you liked in the comments.I write this Substack not from the POV of an editor or publisher, but of an author. There’s a school of thought that writers should pay as little attention to the business side of publishing because it might damage their art, especially if they try and cater to the market. There’s truth to that. But I’ve always wanted to learn as much about the industry not to cater my writing to popular tastes—my first book was a genre-hopping story collection on a independent press after all—but to set realistic expectations for myself. I’ve known many writers who set wildly unrealistic expectations for advances, publicity, and sales…. and then found publishing a book more torturous than joyful. Understanding the industry helps me preserve my love of the far more important thing: the art.

In this vein, I thought I’d bust a few other myths about the industry that I see sometimes.

Before I do, I want to stress that I’ve never pretended traditional publishing is any kind of utopia. There are many problems from low-paid entry level jobs to the impossibility of living of books alone as an author to wasted millions on silly celebrity books that end up bombing. I could go on and on. But I will say two things for traditional publishing. First, the business is fairly healthy and sustainable compared to other industries—including adjacent ones like online media—that are prone to collapse the second capital pulls out or pivots to NFTs, Metaverse, AI, or whatever the next fad is. Big publishing revenue isn’t mind-blowing, but it’s fairly steady. Secondly, many of the people who revel in traditional publishing’s flaws are shilling for even more precarious, exploitative, or unsustainable alternatives. There are many ways self-publishing can work, for example, but the majority of authors find themselves losing money for no return in a seas of scams, manipulated sales, and AI/bot-“authored” garbage. Hollywood and other arts industries are even more focused on celebrities and a handful of breakout blockbusters funding the rest of the industry. Etc.

Okay, here are some facts about publishing you may not know:

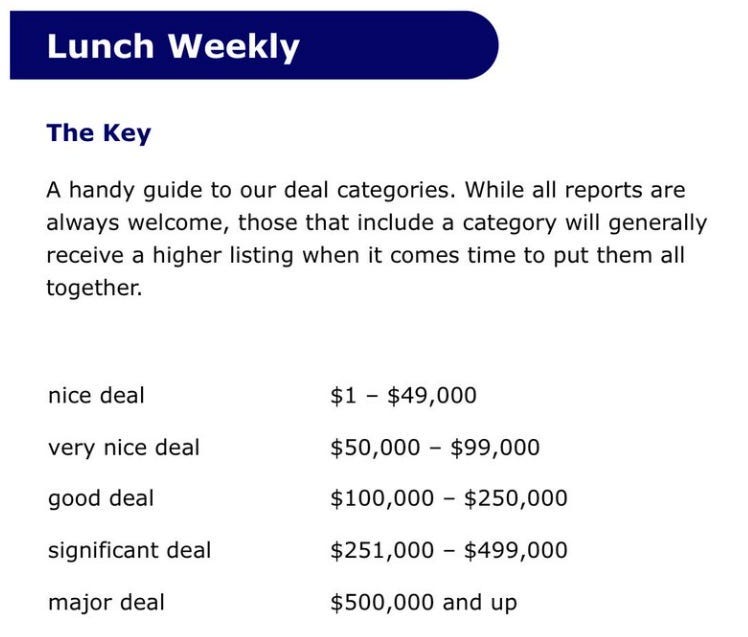

Author Advances Are Often Public

Exact author advances are rarely publicized outside of huge 7-figure deals. Most advances are low and who wants to brag about getting, say, 15k for a novel they spent years of their one precious life on? (On the other end, publicizing a high advance can be fodder for a social media pile-on as a few authors learned during #PublishingPaidMe.) That said, many people aren’t aware that there is a code written into those Publisher’s Marketplace announcement’s that authors tend to share on social media. The code explains the range of an author’s advance. The code isn’t meant to be a secret—PM lists a key on their website—but since most people only see screenshots most are unaware. Here it is:

It’s often remarked that these ranges are huge. There’s quite a difference between 4k and 40k! But as mentioned there are many reasons authors don’t want to be specific about their advances. So, a range is better than nothing.

Yes, It’s Possible to Earn Out (Even without Selling a Single Book!)

There’s a common belief that books “never earn out” and the author advance is the only money an author will see from a publisher. It’s true that the majority of books don’t earn out. (Although as I noted in my last article, this does not mean a book didn’t earn money for the publisher.) Still, it’s not as rare as many imply. I tweeted this recently and lots of authors who are hardly household names confirmed they’d earned out. I earned out on both my short story collection, Upright Beasts, and my novel, The Body Scout. That means if you click on those links and order a copy, I’ll get a (small) bit of money! Of course, the reason I earned out has a lot to do with the fact my advances were low. As you can probably guess, high advance books are especially unlikely to earn out.

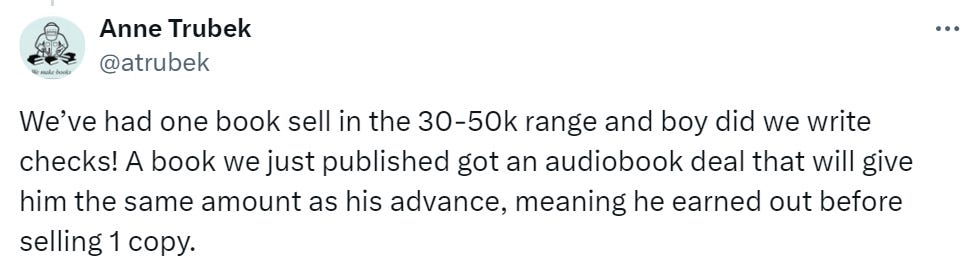

But something else you may not know is that you can earn out without ever selling a single book.

Publishers make money on ways other than book sales. Publishers acquire rights—e.g., audiobook rights, foreign territory rights, merchandising rights—which they can often sell to other publishers. The majority of such sales goes toward paying back the advance. So, it’s possible to “earn out” before your book even goes on sale, as Anne Trubek from Belt Road explains:

Rights are always a part of contract negotiations, and if you as the author keep rights then your agency will try to sell them. Those sales go directly to the author (minus the agent fee).

Why Book Sales Are Hard to Track

In my post, I mentioned BookScan is the only reliable book sale tracker, but that it can’t track all sales. BookScan claims 85% of retail sales and doesn’t track any other sales like library or book clubs purchases (both of which can be a huge percentage of a books sales for certain genres). It might be worth elaborating on why book sales can be hard to track at least as I understand it. BookScan gets “point of sale” reports directly from retailers. That means if you go and buy a book at Amazon.com or your local independent bookstore, those entities will report the sale to BookScan. But many books are sold outside of retail settings and thus can’t be tracked. An author or publisher might sell books themselves at bar reading series, book festival, or a conferences like AWP. Then there are the library sales, bulk book club buys, and other sales that aren’t reported.

Here’s a specific example: I once co-edited and co-published an anthology through a successful Kickstarter campaign. We sold hundreds of copies of the print book—plus more ebooks—but none of these were reported to BookScan because we self-published and sold through Kickstarter instead of retail stores. There was no way for BookScan or anyone else to track those.

It’s Almost Impossible to Distribute a Self-Published Print Book

The reason the aforementioned anthology was sold completely outside of retail stores is that—as we quickly learned—it is basically impossible to distribute a book if you are a mico- or self-publisher. It’s not just snobbery about self-publishing. It’s that most distributors—the companies that deliver books to stores around the country—won’t take you on if you only have one or two titles to sell. You have to be publishing a certain number of titles per year to make it financially worthwhile. Now, you can hustle directly to individual bookstores, as we did to a dozen or so, but it’s quite a lot of work. And without publicity and marketing, you’re unlikely to sell many copies. This is why the self-published world exists almost entirely as online ebook sales through established corporate marketplaces like the Kindle store.

Publishers Do Actually Do Things for Authors

I linked to Richmond’s piece on what publisher’s do for authors above. But just to summarize myself, there really are a lot of things that publishers do for authors even if, yes, I wish they did more. I bring this up because it’s popular to claim it’s stupid to not self-publish since publishers just “take 90% of the royalties without doing anything!” (Note: it’s more like 30-40% than 90% after retail and distribution get their cuts but I digress…) First, publishers do all the basics of publishing a book like copyediting, multiple proofreading rounds, typesetting, acquiring cover art, and printing the actual books. Obvious, but worth enumerating. All of those things can be done on your own, but they require a lot of time and/or money.

Some things publishers do are nearly impossible to replicate on your own. I explained distribution above and that’s huge when we’re talking about print sales. Most people still buy print over ebook or audio, and they buy mostly from Amazon or else physical bookstores. You just aren’t likely to sell many copies of a print book unless you can physically distribute it to major retailers and indie bookstores. Publishers also can get your book reviewed in trade publications (Kirkus, Library Journal, etc.) and hopefully some non-trade magazines and newspapers. Again, very hard to get those without a publisher mostly because of the sheer volume—I’ve seen estimates in the millions—of self-published titles that appear each year.

Publishers Are an Author’s Business Partner not Employer

A lot of viral publishing hot takes rest on a confusion of the actual relationship between authors and publishers. A viral article a few years ago argued that publishers should force established authors to mentor their debut authors. I often see questions about why publishers don’t pay a living wage or provide health insurance. Etc. Obviously, I’d like every author to have a living wage and health insurance but the relationship between author and publisher isn’t that of employer and employee. As an author, you are a self-employed business yourself. Your publisher is more of a partner working on specific projects, which is why authors can sell books to multiple publishers at the same time. Anyway, this is useful to understand both for a general expectation settings as well as financial specifics. E.g., a publisher is not going to take out taxes from your “wages” and on the other hand as a self-employed business you have the ability to deduct business expenses and set up your own retirement plans. I get into that here:

Write-Off What You Know

Okay. I’m getting the “near email length limit” warning so that’s probably enough for one post. Now, I’m going to go read and maybe even buy another book.

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.”

Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

Right now, my micropress is operating more like a cooperative than anything else, after our sales dropped into the sub-basement in 2021. I could give up, I suppose, but after 20 years I just can't. I may have taken on too many writers more interested in getting published than selling books, but their books are all terrific, in my opinion, and deserve to be read. Excelsior! as Stan Lee used to yell.

Small indie publishers are struggling. Some are closing their doors. The big-name publishers won't look at your ms. if you don't have a big-name agent. So, you submit to the small indie publishers who you think might be a good fit. And you wait. If you're lucky, you might receive a kind word with your rejection notice. Some don't answer at all. At some point, you self-publish and hope someone bothers to buy the ebook version or the paperback and read it. I'm 76 and publishimg my first novel. I'm not expecting money or fame, but it'd be nice to be read.