Fix Your Hearts or Die!: A Short Ode to David Lynch (RIP)

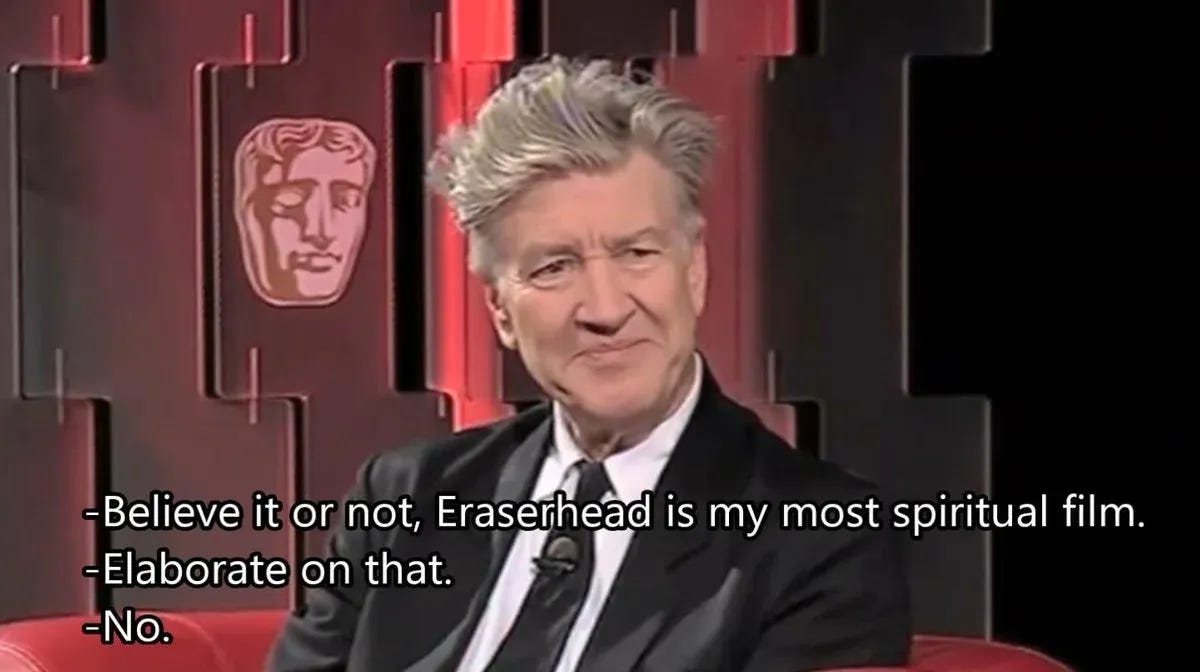

A tribute to the late, great master

David Lynch passed away today at the age of 78. He was one of those artists whose name calls for effusive adjectives—visionary, legendary, genius—and whose influence on American art is incalculable. What would “prestige TV” be without Twin Peaks? What would modern cinema be without Blue Velvet, Mulholland Drive, and more? What would American art be without the countless artists he inspired?

When a great artist dies, it is common for people to lament. But death is always an opportunity to celebrate life and to honor the artist’s work. Especially an artist who created a body of work as large, varied, and glorious as Lynch’s. I did not know David Lynch professionally much less personally, and will not pretend to speak of the man. But David Lynch the artist was a great inspiration to me, as he was to countless others I know and don’t know.

In many ways, Lynch was the ideal of an artist to me when I was starting out. Someone with a clear artistic vision, yet who constantly pushed his work in new directions. Who left the forms he worked in expanded. An artist who scrapped and fought to do things his way without tailoring to popular tastes and trends. And someone who knew that the art itself was the meaning and it could never be reduced to simple lessons or messages.

When I boy growing up in rural Virginia, my family had a VHS player and couple blank VHS tapes. We didn’t have cable back then, much less the modern buffet of streaming options, and we would record movies broadcast on TV so we had something to watch when nothing was on. At some point, I recorded Lynch’s Dune on one VHS. I never taped over it. Dune became one of the handful of movies I watched over and over. Yes, I know it is a flawed movie (and Lynch himself largely disowned it), but even a flawed Lynch was a revelation to a weird, alienated boy uninterested and uninspired by most of the blockbusters in theaters and novels assigned in class. Dune was weird. It was transgressive, bizarre, and—despite all its structural flaws—filled with imagery that still feels more otherworldly than most science fiction since. I wrote a little ode to the film on the eve of the Villeneuve version.

Of course, Dune is not among Lynch’s greatest works. When I was old enough to drive and rent tapes myself, I devoured what I could find at the local Blockbuster. His works were filled with images, characters, lines, and scenes that are burned into my artistic brain. I admire everything I’ve seen from Eraserhead to the underrated Wild at Heart, although his greatest works strike me—and these are hardly controversial picks—as Blue Velvet, Mulholland Drive, and Twin Peaks. I include both the original Twin Peaks and The Return there, each of which is a stellar achievement that would justify the entire careers of other artists. Lynch and co-creator Mark Frost more or less created cinema-quality “prestige TV” with Twin Peaks and exploded the entire form twenty-five years later with The Return.

Much has been made of Lynch’s surrealism and strangeness. I’ve written about it before too. His work diverges in some ways from the official capital-S Surrealists, but he was one of the greatest dream artists whose works really do feel like dreams and nightmares. His artistic practice, from building stories around images that appeared to him during Transcendental Meditation to his embrace of artistic accidents, always fascinated me. His strangeness has been written about plenty before though.

Outside of his particular brand of Americana surrealism, I have always admired Lynch’s ability to blend tones. His works are sometimes called horror films, but they are much more than scary. They are filled with humor, playfulness, earnestness, mysticism, and romanticism. These sit side-by-side with the horrors and darkness. Indeed, he had an uncanny ability to pivot tones from scene to scene. One way he achieves this is by how he recontextualizes the familiar. Of making the banal feel spiritual, common horrors seem funny, and the unremarkable turn terrifying. Few other artists can build, for example, such dread out of a plastic telephone or a conversation in a diner. Or who can make a mug of drip coffee seem spiritual.

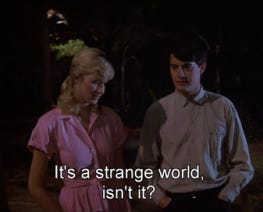

There’s no more iconic example than this scene in Blue Velvet where a romantic 60s pop song is imbued with terror and turned into a surreal nightmare.

Some mistake Lynch’s humor, strangeness, and tonal shifts for a sort of cynicism. They think his work is merely interested in the shocking or surprising. They are, in my view, dead wrong.

Perhaps the most laudable part of Lynch’s art is that it is filled to the brim with humanity. Lynch believes in the hearts of people and his work shows true wonder at our existence. When Lynch pivots to romanticism and earnestness, he means it.

There are so many examples one could list here, from Lynch’s portrayal of transness back in the 90s and his appearance in The Return telling those who would deny the humanity of others to “fix [your] hearts or die” to the focus on the fullness of his tragic characters’ lives and the grief of their loved ones. (The accusation that Twin Peaks was another “dead white girl” show always felt off to me for this reason. Other shows treat the dead, especially dead women, as mere plot fodder. Twin Peaks always centered Laura Palmer. Her life. Her hopes. Her loved ones. Her story.)

Another way to say all this is Lynch’s work reminds us that life is everything. It is horror. It is beauty. It is sorrow and laughter and violence and wonder and love and dreams. It is all of that, all together, all in one confusing and unbelievable tangle. A beautiful mystery.

At least, that is what his art says to me.

I am sad that Lynch is gone, but will remain thrilled that his art is there for me—and you and everyone else—to experience over and over again.

If you enjoy this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout—which The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent”—or preorder my forthcoming weird-satirical-science-autofiction novel Metallic Realms.

I can literally pin-point my inspiration to become a filmmaker to a single moment in the Twin Peaks pilot episode, when Lynch ,seemingly randomly, cuts to a close up of Audrey's saddle shoes as she gets in the car driving her to school. The viewer's brain goes, 'huh?' That was weird. The payoff of course comes in the next scene when she switches to red high heels once at school. It was an epiphany of how what we point the camera at gives it meaning, and in the hands of great directors, multiple layers of meaning. A sad day, but, like you say, a reminder to appreciate a great artist.

Nothing has made me feel more intensely and wondrously than Twin Peaks. Lynch was the greatest, and his work (including his paintings) has meant the world to me. A while back I co-edited an online volume of essays on season three if anyone is interested: https://nanocrit.com/index.php/issues/issue15