Fear of the Surreal

On David Lynch, surrealism, and hating art that "makes you feel weird."

My last post was about different modes of fabulist literature with a focus on magical realism and surrealism. Writing it got me thinking about how almost 100 years after Breton’s first Surrealist manifesto surrealism remains disrupting and confounding. I don’t mean surrealism in the surface-level sense of “lol so weird and random” imagery, which is now so commonplace it’s the default mode of Super Bowl ads. I mean surrealism as art that resists simple meanings and concrete interpretations. As an artistic mode that seeks to evoke the subconscious and inspire a variety of individual interpretations.

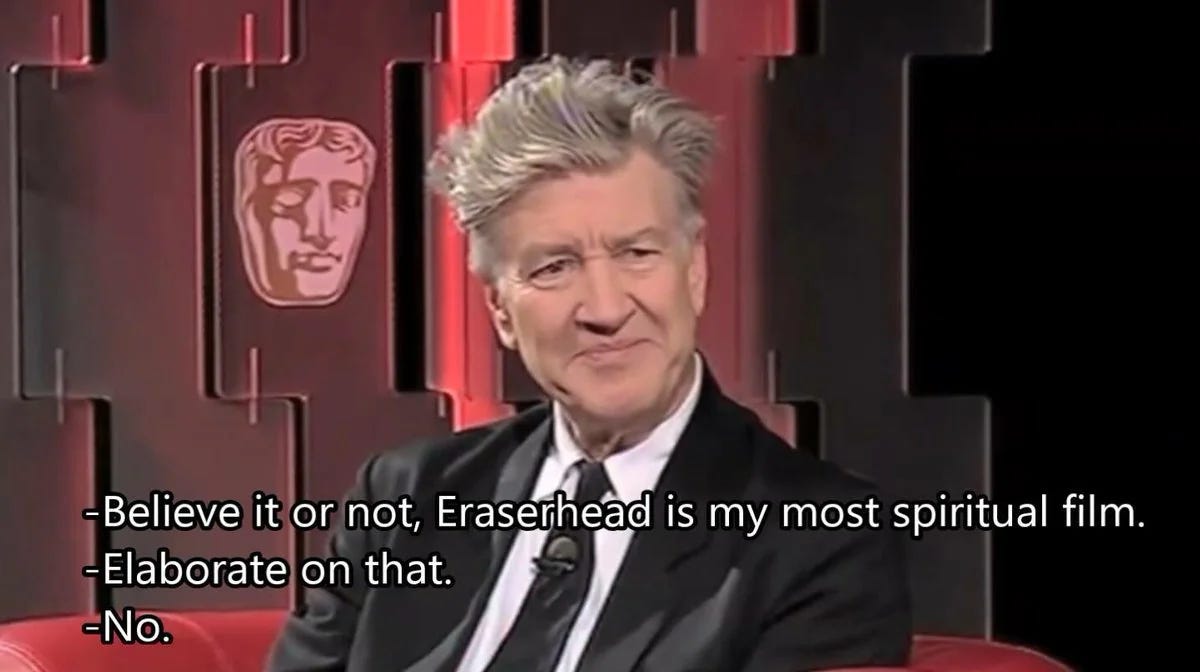

I was also thinking of this recently as I saw people arguing about the “right” meaning of David Lynch’s films. Their arguments weren’t bad as interpretations, but the framing—“actually his movies mean X not Y”—stuck out to me because Lynch rather famously refuses to reduce his work to simple meanings: “I don’t ever explain it. Because it’s not a word thing. It would reduce it, make it smaller.” Lynch is not trying to make simple allegories or use reductive metaphors. He famously creates works from images that appear to him during transcendental meditation and embraces accidents and mistakes during the creative process. “I don't know why people expect art to make sense,” he says. “They accept the fact that life doesn't make sense.”

(One might argue many don’t accept that life doesn’t make sense, thus the popularity of organized religion and inflexible ideologies. But I digress…)

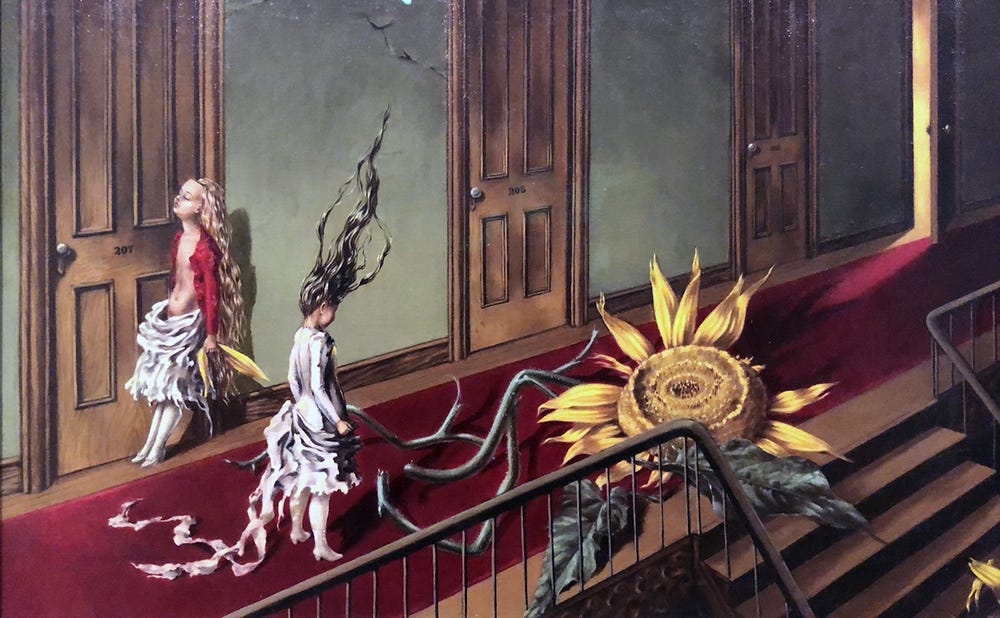

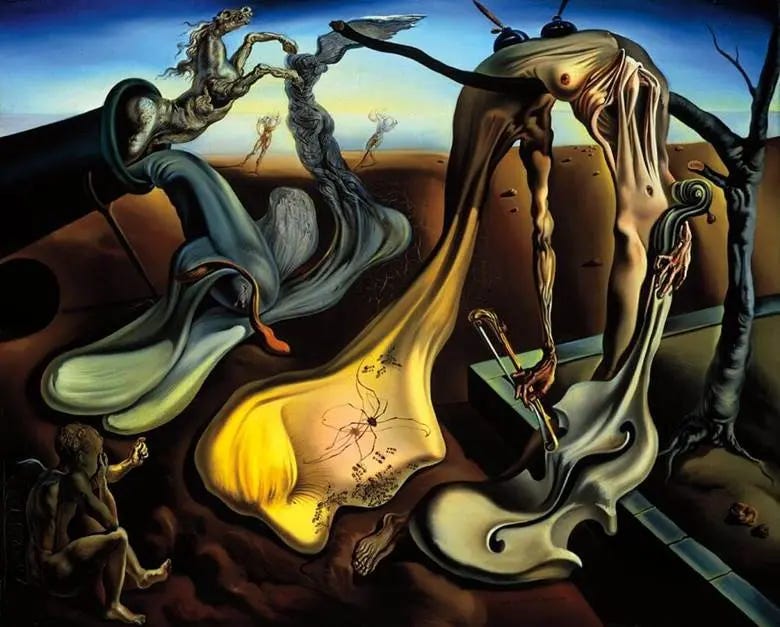

Surrealism in the original capital S sense was, in part, meant to destabilize established notions of art as well as traditional ways of thinking. (This was a political project for many Surrealists, an attack on the “rational” ways of thinking that had lead Europe to the devastation of World War I and would lead to World War II.) There’s endless things one can say about the Surrealists but one aspect I’ve always been drawn to is the rejection of traditional symbols loaded with established meanings in favor of new ones—typically drawn from dreams or with methods of producing intentional randomness—open to whatever interpretation the viewer wanted. For much of history a viewer of a painting in say Western Europe would know what various symbols meant. A lamb is a symbol of Jesus. A pomegranate references the underworld. Surrealists instead confronted viewers and readers with bizarre imagery that avoided no fixed cultural meaning or else subverted established meanings.

This was a radical idea in some ways. The precursors to Surrealism tended to have containable meaning even when they were bizarre. E.g., the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch many surreal monsters and magical happenings yet the were meant to convey fairly conventional Christian messages. There’s a guardrail there for the viewer. (Or there was at least. These days his work is decontextualized and has perhaps gained a new surrealism.)

It feels like even 100 years of surrealist art, readers and viewers still need such guardrails. They seek containers to put the unreal in. Surrealism, whether with a capital S (to mean the “official” Surrealist movement) or a lowercase s (to mean any artists who employ similar modes and methods), still confounds.

This is true even of people drawn to strange works. As I mentioned in my fabulist article, I’ve had many conversations with SFF authors and readers who deride the surreal and magical realism as “lacking rigor” or having “failed worldbuilding.” There’s a desire for systemized rules to contain the unreal. In the MFA/literary world, coherent and logical worldbuilding might not be a requirement but there is a desire for clear allegory and metaphor to contain the magic. Readers can accept magical elements if they feel they can pin a specific meaning on them. Latin American magical realism reflects the experience of the colonized. Kafka is a writing allegories of postindustrial anxiety. Etc. It’s not that such readings are wrong—much of (though certainly not all) Latin American magical realism is concerned with the effects of colonialism and Kafka certainly drew dark inspiration from the alienation of the modern world—but that they are reductive. The the stories of Borges or Marquez or Kafka story are about many things. The magic is multipronged.

At least that’s the case in what I consider great art, and those three are great. Many lesser authors of the magical do indeed seek blunt metaphors and one-dimensional allegories. At the risk of being an old man yelling at clouds, such works seem more prevalent than ever. (As a side note, it strikes me that the most welcoming home for weird art that resists simple interpretations these days is horror fiction. Indeed “weird fiction” is considered a subset of horror. Perhaps this is because horror is meant to unsettle and “it weirds me out” is reason enough to accept the bizarre in that framework...)

An amusingly goofy version of the need for guardrails—or here really handholding—in art is this viral tweet from some Ayn Rand loving guy who claimed to prove there is “objectively” good art by listing a bunch of quite literally subjective criteria. But even more than the question begging and silly framework, it’s interesting how scared such people are of art that resists simple interpretation. The worst thing, apparently, is art that “makes you feel weird” or “confuses the mind.”

This guy is likely just a bait account, but this attitude in a less trolling form is pretty pervasive these days. We live in an era of simplistic interpretations where across the political spectrum people expect art to be some kind of moral instruction. If something is unreal, it must be straightforward allegory and that allegory better have the right political message. These readers seek art that reflects their own values back at them rather than what challenges their perceptions or inspires new ways of thinking. Of course, what I’m grumbling about isn’t new. Susan Sontag wrote “Against Interpretation” in 1964 well before I was born: “The modern style of interpretation excavates, and as it excavates, destroys; it digs ‘behind’ the text, to find a sub-text which is the true one.” But it does feel the problem is increasing in an era where venues for criticism have all but disappeared and what’s left are simple readings that can be crammed into short tweets, brief TikToks, and bullet point lists of favorite tropes.

Anyway, it’s surely pointless to protest the overwhelming desire for containable art and one-dimensional interpretation. Perhaps all we can do is celebrate the art that does resist. To seek out the strange and the wondrous. To embrace different even conflicting readings without worrying about a singular “message.” And perhaps above all to simply let art make us feel whatever strange thoughts and sensations it provokes without worry about what it means.

It seems appropriate here to end with a quote from 99 years ago in “The Surrealist Manifesto” when Breton notes “the hate of the marvelous which rages in certain men, this absurdity beneath which they try to bury it” and responds: “Let us not mince words: the marvelous is always beautiful, anything marvelous is beautiful, in fact only the marvelous is beautiful.”

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.”

Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

Thank you for these cogent thoughts. As you will not be at all surprised to hear, I'm completely with you on the weird horror connection. The emotionally and philosophically destabilizing effect of this kind of storytelling, and not just that, but the same effect arising in its accompanying sub-literature of weird philosophical and essayist rumination and speculation, is one of our most important ongoing literary-artistic connections to the numinous, to the primal reality behind rational, visible surface appearances, that both undercuts our attempts to build a hyper-rational human order of things and provides life-giving meaning to it. It's no accident that weird storytelling in both literature and film has become ascendant here in the early 21st century. The story of Jung's transformative flood of inner psychic imagery, which he later interpreted as a kind of psychological presaging of World War I, comes to mind. It's tempting to speculate that we are now experiencing a collective version of that, though exactly what it portends is unclear. All that's clear at present is that something deep has become unmoored. In such a circumstance, weird storytelling, including Lynch's brilliant brand of surrealism, becomes a major conduit for expressing our unease to each other.

This might be a good place to insert a more global perspective. Have you looked at the histories of surrealism in African literature? I think they show how some literary cultures have since abandoned the binaries of meaning imposed on the surreal. Nigerian writers Ben Okri and Amos Tutuola pull off some pretty fantastical things. There might even be connections made with the recent modes of speculative fiction from Afro-African American authors and these histories. I think my point is that some literary geographies work with the marvelous in ways that might benefit your argument.