Genres Are Historical and Cultural, Not Scientific

why rigid rules for genres never quite work

This week, Joyce Carol Oates—literature’s greatest shitposter?—got the internet riled up over her interpretation of Ted Chiang’s definition of science fiction and fantasy. Oates somehow tied YA into the debate, which is always good for starting twitter fights. (Side note: please read Erin Somers’s great profile of Oates from this month!)

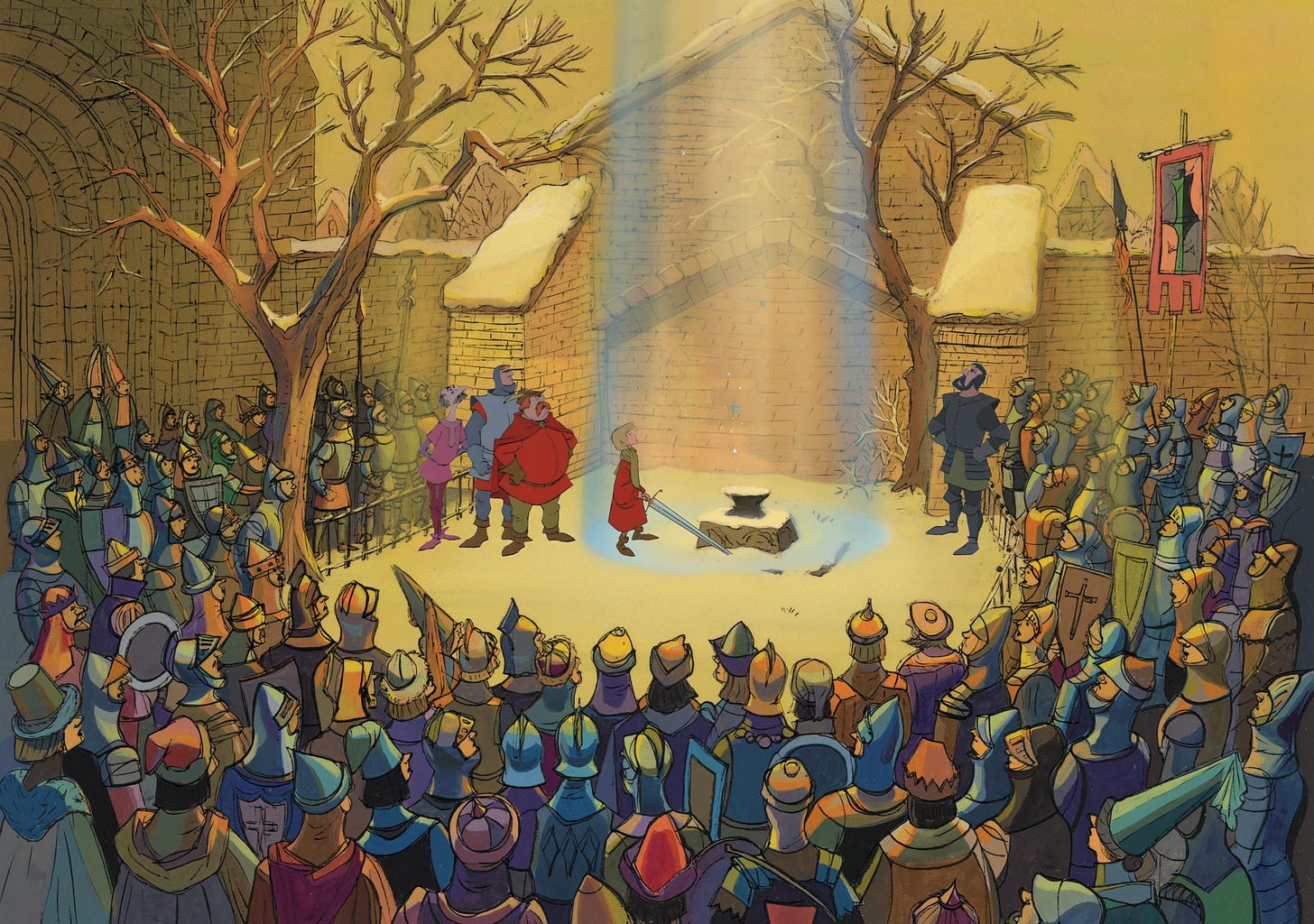

Chiang’s actual definition of SF vs F is an interesting one, although certainly people can disagree with it. Chiang basically argues—if I understand him correctly—that science fiction operates with a mechanistic, objective universe in which the rules apply equally to everyone while fantasy operates with an interested universe that recognizes the personal. Think destiny and prophecy vs. chemistry and calculus. A SF spaceship travels at the same speed regardless of how noble its captain is, but only “the true king” can pull the sword from the stone. This explains why, say, a story with time machines anyone can theoretically use is science fiction but a story where only Time Travel Man or only a select group of “time bending” wizards can time travel is fantasy.

This taxonomy doesn’t perfectly fit traditional science fiction and fantasy lines, although I’d argue that’s exactly why it’s interesting. Star Wars has the cosmetics of science fiction—spaceships, robots, etc.—but it’s worldview could be considered fantasy: special people have magical powers and good fights evil in a grand struggle. On the other hand, Ted Chiang himself writes many excellent stories set in alternative science worlds—where the science works differently than we understand it today—that could be called fantasy but certainly feel more like science fiction.

(I wrote a bit more about this idea here. Also do yourself a favor and read Ted Chiang. He’s a genius, no matter what label you want to put on his work.)

Still, there’s plenty of counterexamples to this taxonomy. Not all fantasy novels have chosen one narratives and it’s possible to write “scientific” magical systems in which anyone can create the same magic spells chanting the right words or using the right ingredients. One could argue there’s no real difference between a species of aliens who have powers beyond our understanding and a fantasy story with elves or fairies. Etc. Basically, you can poke plenty of holes in the theory.

But I’d argue that every attempt to classify genres in a rigid way is bound to fail. This includes the definitions that people were using to refute Chiang’s taxonomy. People love rigid definitions that easily sort all works of art into a few handy boxes. But art never quite fits. The boxes overflow.

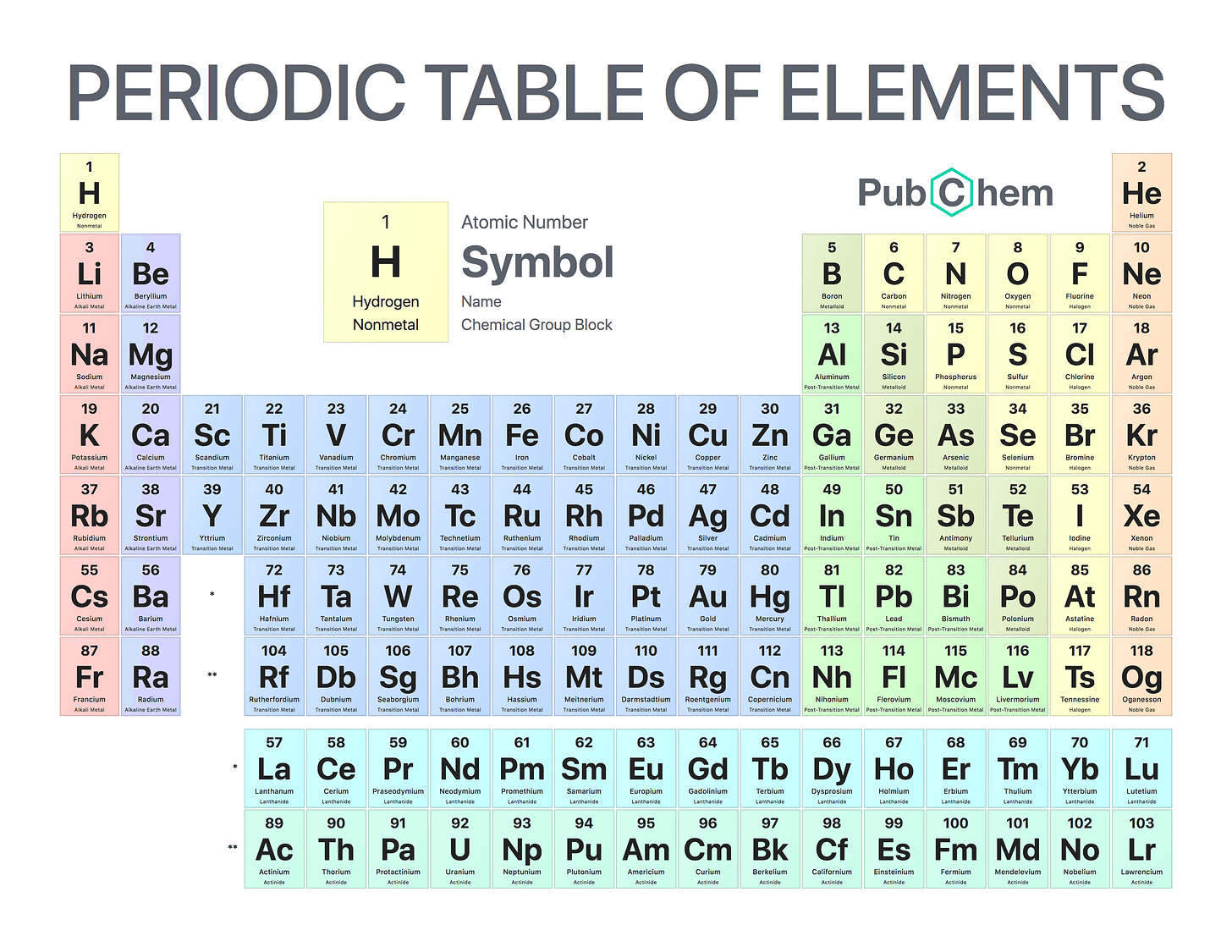

Genre is not chemistry or physics. There are not a set of rules we can apply to genres that always hold true or which we can use to sort works of art from across time and culture. There isn’t anyway to objectively measure if a story is genre x or genre y.

Take a genre as seemingly straightforward as “horror.” Most would define it along the lines that Wikipedia does, fiction “intended to frighten, scare, or disgust.” But this isn’t how things break down. Countless works of “horror” are comedic in tone or otherwise not scary, yet we call them horror because they include elements we consider part of the horror genre. A melancholy werewolf story or an satirical vampire story will be called horror nine times out of ten. On the flip side, many terrifying novels about abuse, trauma, war, climate change, and so on are left out of the horror section. “What’s scary” isn’t actually anyone’s metric.

Why are some terrifying mythological monsters—e.g. zombies and vampires—placed in horror and other terrifying mythological monsters—e.g. dragons—placed in fantasy? The answer, I think, is that genre is always historical and cultural. Over the course of literary history, different elements and tropes have gotten associated with different genre labels. Books like Lord of the Rings and it’s heirs led dragons to the fantasy camp while works like Dracula and its heirs led vampires to the horror camp. A different literary history would have led to different classifications.

It’s important to note here that genre boundaries do not break down the same ways in other cultures or in other time periods. French literature, for example, has a genre called fantastique that is different from—and predates—the Anglo conception of fantasy fiction. Fantastique, in Anglo literary terms, is a kind of horror/fantasy hybrid where the supernatural appears in realistic stories. It’s close to what we call “weird fiction” and wouldn’t include your Wheel of Time and Harry Potter type epic fantasy novels that most Americans think of as epitomizing the genre. There’s a fascinating book translated as The Fantastic by Bulgarian-French theorist Tzvetan Todorov I recommend. Years ago, I stumbled upon a debate in digitized pages of an old SFF magazine where American SFF authors and critics ranted about how Todorov was “wrong” because his description of “the fantastic” didn’t line-up with the Anglo idea of fantasy! (If anyone remembers what I’m talking about, please link in the comments)

And of course the taxonomies we use today, in 2022 English literature, are quite different from what was used in, say, the 19th century of “Gothic fiction” and “novels of manners.” We don’t even have to go back to the 19th century. The concept of “Young Adult” as a distinct genre is a phenomenon of the last twenty years or so, and it’s lead to countless works being retroactively reclassified as YA.

This isn’t just a semantic debate. Failing to understand that genres are cultural and historical leads to misunderstanding. It’s leads to American writers claiming things like “magical realism is just fantasy for snobs”—or even worse assuming that anything non-realist by a Latinx author must be “magical realism”—as if all cultural contexts can be subsumed by contemporary American ones.

More than once, I’ve had conversations with established SFF authors and critics who claimed that surrealist and magical realist authors were “just fantasy” while simultaneously dismissing those modes as lightweight for “lacking in worldbuilding rigor.” You can’t get mad at someone not following your rules when they’re playing a different sport.

If I had to pick a metaphor, I’d say literary genres more closely resemble cuisines than chemistry. Cuisines don’t have rigid and universal rules. What was Italian cuisine before the introduction of new world ingredients like tomatoes is obviously quite different than what it is today! Cuisines are shaped by history—see map above—but have porous borders. Cuisines are ever-shifting, ever-overlapping, and ever-changing. New ingredients are introduced, new hybrids formed.

Similarly, genres are ever-shifting, amorphous concepts. Whenever I read science fiction from the 1930s-70s, I’m struck by how little those authors cared for ideas of strict worldbuilding logic than dominate today. Twenty or a hundred years from now, many of the books we consider staples of genre X will be thought of as some new genre Y. Change is the constant.

Anyway, I could rant about this for quite some time so will try to wrap this up by saying that genre taxonomies are useful for writers only insomuch as they the reveal story possibilities. Chiang’s taxonomy is open to hole poking, but I do think it provides an interesting framework—from a craft perspective—for how to deploy your speculative elements. Do you want them deployed in an objective, impersonal way or in a personalized way? Each path leads to different possibilities. If a framework doesn’t feel illuminating to you, well, ignore it. There’s no strict genre rules or immutable labels, only different taxonomies in different times and contexts.

As always, if you like this newsletter, please consider subscribing or checking out my recently released science fiction novel The Body Scout, which The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent” and Boing Boing declared “a modern cyberpunk masterpiece.”

I think the genre conversation falls flat so often because it focuses too much on the stuff - the werewolves, fairies, aliens and whatnot - and not what that stuff is used for. And that’s...not very useful analysis, as an author or a reader.

You can claim that you’re a horror writer because you’re into haunted houses, fine, but that still doesn’t tell me what kind of horror writer you are. What’s your artistic lineage? A story in conversation with Stephen King would be very different from one in conversation with Ursula K. LeGuin. Genre hot takes seem like just that; hot takes, not analysis.

I went to art school (the jokes write themselves) and we couldn’t just slap ‘postmodern’ onto everything we made. We had to actually name specific periods and micro-trends in our work, no matter how stupid or obscure. I don’t know why writers are so averse to doing the same.

All of this to say that I really appreciate you and Chiang making these thoughtful observations. They’re very much needed!

Ted Chiang is amazing. Thanks for the wring this.

I think any "taxonomy" -- either it is fiction, music or species classification -- has a dual implication. At one side, a rigid boundary. We humans like to categorise, put things in their places when on the other side, we know they can move from one place to another very easily. I think you summed it up here nicely, "genre taxonomies are useful for writers only insomuch as they the reveal story possibilities".