Don't Draft Shakespeare into Your Genre Wars

Plus asshole autofiction and a history book recommendation to understand the chaos of the news

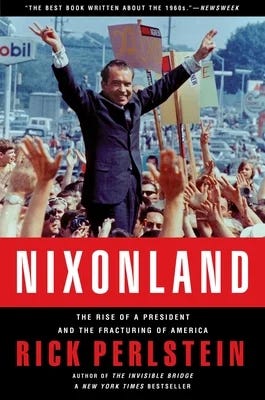

History to Understand Today

I don’t write about politics much in this newsletter. Not because of any silly notion that art is above or separate from politics, but because I waste enough of my life ranting about it in person and on social media. It’s nice to have a place to just talk about books. And anyway I’m inclined to think social media is one of the most anti-revolutionary forces humanity has invented. A place to sap away all energies and hope. No amount of “posting from the imperial core” has a meaningful effect. The real work is elsewhere. That said, given the ongoing horrors and chaos we are witnessing, especially the recent killing of Renee Nicole Good and escalation in the Twin Cities—I recommend this dispatch from Minnesota published by Daniel Oppenheimer—and the mockery and even revelry about the killing coming from parts of the right, I’ve been thinking about Rick Perlstein’s history of the rise of Richard Nixon: Nixonland. So much of what we are seeing today recalls that time period. For example, here’s a passage detailing the reactions to the Kent State shootings when the Ohio National Guard opened fire on unarmed protestors from 100 yards away, killing four students, one of whom was not involved in protests and simply walking to class:

A respected lawyer told an Akron paper, “Frankly, if I’d been faced with the same situation and had a submachine gun . . . there probably would have been 140 of them dead.” People expressed disappointment that the rabble-rousing professors—the gurus—had escaped: “The only mistake they made was not to shoot all the students and then start in on the faculty.”

When it was established that none of the four victims were guardsmen, citizens greeted each other by flashing four fingers in the air (“The score is four / And next time more”).

The passage goes on for some time, including a quote from a father who had multiple sons attending the university and still said, “It would have been better if the Guard had shot the whole lot of them that morning.” Is it comforting or just more horrifying to know that the bloodlust, casual dismissal of human life, and need to treat even tragedy as sport are not unique to 2026, the internet, or Donald Trump?

That history rhymes is old hat. But if you, like me, are young enough that you did not live through the 60s and 70s, and were taught only the sanitized hippie mythology of that era, then Nixonland is an eye-opening read. Perlstein strikes a good balance of storytelling and scholarship, and even though the book was published in 2009, I do not think anyone can read it today without thinking about how much of Nixon and the violence and chaos of that era is recurring (in both farce and tragedy) today.

Asshole Autofiction

When I’m not watching the chaos and horrors in the news, I’m jumping between a variety of older books. One of those, which I imagine I’ll write about at length soon, is Self-Portraits by Osamu Dazai. Dazai (1909–1948) is one of Japan’s great writers, and a self-mythologizing and rebellious literary figure on par with—though quite different in temperament and style—Yukio Mishima. Like Mishima, he also had an obsession with suicide. Although instead of seppuku, Dazai’s five suicide attempts were hangings, overdoses, and drownings. Several of these were lovers’ suicides where either both, or only he, survived. (The last was successful for both.)

Reading these stories from a hundred years ago and half a globe away, I find them both strange and familiar. What felt excitingly alien was the freedom of form and style. Many of these are short pieces that would be hard if not impossible to publish today outside of, I suppose, one’s personal blog or Substack. What is familiar is how these stories are inspired by his biography without being memoir. Yes, they’d be called autofiction today. But unlike most autofiction one reads in 2026, Dazai doesn’t seem concerned with exonerating or flattering himself. The Dazai characters are by turns pathetic, neurotic, devilish, and just plain jerks. In previous Counter Craft posts, I’ve alluded to my “Asshole Theory of Autofiction.” (TL;DR = autofiction is boring when the author flatters themselves and best when the author embraces their inner loser, asshole, failure, and fool.) When I finally write that essay, Self-Portraits will be a central text. Anyway, read these stories. They’re fantastic.

Don’t Draft Shakespeare Into Your Genre Wars

One refuge from the news is small stakes literary scuffles. What else are we on literary Substack for, anyway? One silly discourse that caught my attention was bickering about whether William Shakespeare was a “genre writer” or a “literary writer.” I’ve hidden the user names because I’m not trying to dunk on any individuals (and I think the “outright literary” poster is being at least a bit tongue-in-cheek). Still, anachronistic shoehorning of past writers into “teams” based on contemporary literary divisions is a pet peeve of mine. Was Jane Austen a commercial Romance writer? Did Homer write fan fic? Should we call Anton Chekhov MFA fiction? No. Be quiet. Isn’t Tumblr still around to quarantine these takes?

Seriously though, I write a lot about the question of genre fiction and literary fiction because I think these are interesting traditions and that learning about them can deepen your understanding and appreciation of literature. As I wrote in my “The Grand Ballroom Theory of Literature” essay, I like to think of literature as a unending part in a vast ballroom the stretches throughout time. Genres and styles are conversations that take place between authors (and readers, editors, etc.) in that ballroom. Genres aren’t mere marketing labels. They are conversations where authors speak, rebut, compliment, and subvert each other. This, for me, is an illuminating way to think about books.

The “team” types of takes do the opposite. This sports fan mindset where you pick Team Literary or Team Genre (or whatever) and then draft authors to your side, regardless of actual history and context. What does it mean to say Jane Austen was a commercial Romance author when IRL Austen’s novels of manners sold in small numbers to an audience of landed gentry? How is it illuminating to claim Shakespeare was a “genre writer” or “lit fic writer” when neither of those terms existed in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England in the way they do today? Or to claim Shakespeare was “lowbrow” or “highbrow,” “populist” or “elitist”? Shakespeare’s plays were performed for, and funded by, both commoners and the royal court. It doesn’t get more “elite” than the Queen, right? Then again, Queen Elizabeth and the English nobles were also fans of the most “lowbrow” and “populist” entertainment of the day: watching dogs maul chained bears and gladiator chimp fights.

Times do change. If you think overeducated literary snobs adjuncting at MFA programs are elites, that’s fine. But surely they are not elite in the way of a literal queen or king. Our current concepts of genre fiction and literary fiction began in the 20th century and are tied to specific material and cultural conditions. As Dan Sinykin has noted, the term “literary fiction” didn’t even exist until the 1980s when authors sought to distinguish themselves from the popular commercial fiction of the day. That is to say, from “airport novels” that are so named because they were sold in airports, grocery stores, and drugstores. These are not the conditions of literature in Elizabethan England.

Ultimately, genres are not scientific categories that we can sort authors into by studying their chemical properties. Genres are always historical and cultural. Different cultures, and different eras, have different taxonomies and traditions. Our genre labels are constantly morphing, diverging, and changing.

Genres Are Historical and Cultural, Not Scientific

This week, Joyce Carol Oates—literature’s greatest shitposter?—got the internet riled up over her interpretation of Ted Chiang’s definition of science fiction and fantasy. Oates somehow tied YA into the debate, which is always good for starting twitter fights. (Side note: please read Erin Somers’s

One thing that makes modern genres interesting is that they are often not mere loose groupings of texts based on shared properties but entire literary ecosystems. The Odyssey, Star Wars, As I Lay Dying, Thelma and Louise, and Lolita are all “road trip” narratives. They are a genre in one sense of the word. We can create infinite genres based on loose shared properties. Marriage plot novels. Coming of age stories. Internet novels. Etc. However, a genre like “science fiction” or “horror fiction” (and attendant subgenres like “cyberpunk” or “cosmic horror”) are not merely collections of works with some shared subjects or tropes. These are full ecosystems with editors, publishers, critics, literary magazines, fanzines, awards, and so on working with authors to collectively create meaning as well as both opportunities and limitations.

Anyway, my real frustration with these conversations is how many people speak in proud ignorance. This is as true of the literary snob dismissing all science fiction novels as mere escapism without literary weight or style as it is of the genre fan who mocks literary fiction without knowing anything about it. On one social media platform I waste time on, there is a SFF author who every month or so goes on a tirade about contemporary literary fiction being defined by “sad boner literature” about sad male professors having affairs. I’ve never once seen him name a single contemporary novel he’s read that fits this, much less a large number of them that would even constitute a trend. (Nor does he seem aware that contemporary literary fiction is in fact written by quite a lot of women.) Of course, maybe he’s just trying to turn it around on all the literary snobs who for decades said that SFF was just a genre for dorky dudes to write about boning aliens and elves.

Perhaps proud ignorance is just the mode of the day from politics to prose. C’est la vie. What can you do? Well, one thing you can do is read widely yourself across genres and styles. If you’re a literary reader looking for science fiction to try, my last article recommended the works of Gene Wolfe. And if you’re a reader of any kind, maybe try Osamu Dazai?

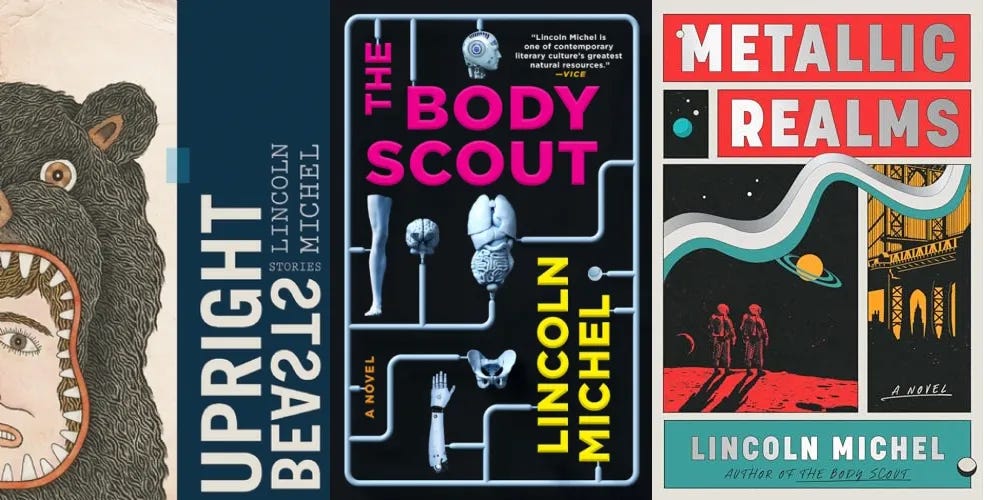

My new novel Metallic Realms is out in stores! Reviews have called the book “brilliant” (Esquire), “riveting” (Publishers Weekly), “hilariously clever” (Elle), “a total blast” (Chicago Tribune), “unrelentingly smart and inventive” (Locus), and “just plain wonderful” (Booklist). My previous books are the science fiction noir novel The Body Scout and the genre-bending story collection Upright Beasts. If you enjoy this newsletter, perhaps you’ll enjoy one or more of those books too.

I miss airport novels, and racks of paperbacks that enticed readers of diverse social strata and educational levels with vivid covers. I miss middlebrow authors and broad-appeal fiction. Literary versus genre is another tedious squabble that adds to the din of this cheerless, quarrelsome age.

my judgemental take on the whole Shakespeare thing is that people on here don’t really understand drama as a medium