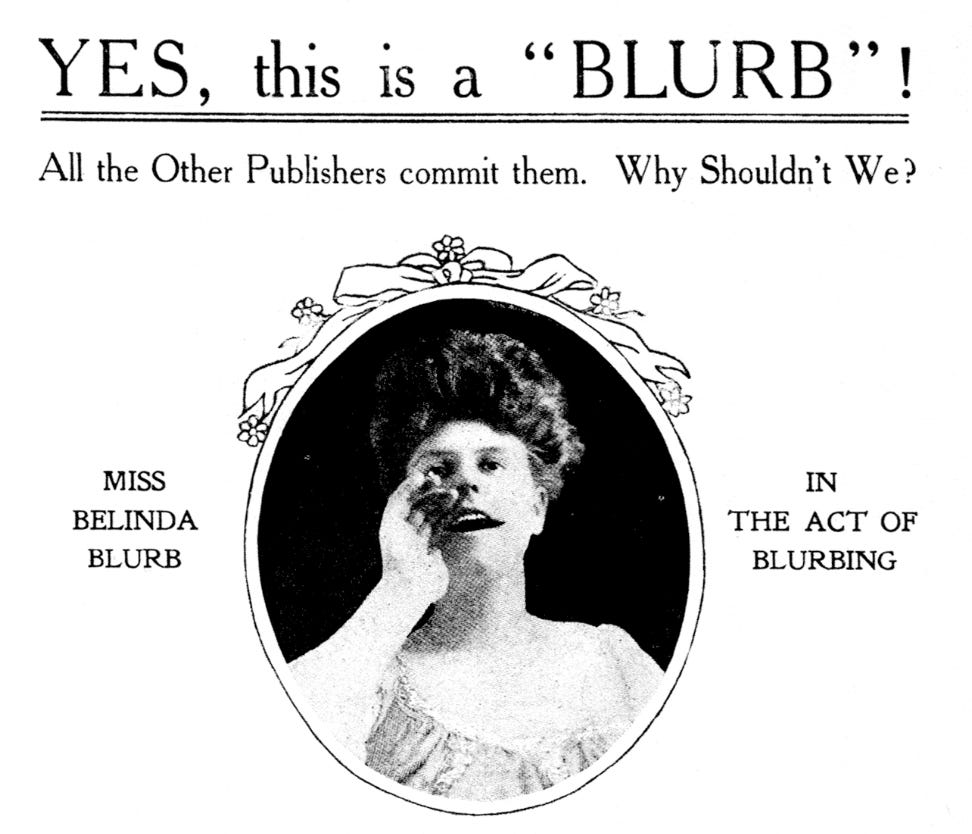

A Luminous, Brave, and Unputdownable Article about Blurbs

Or just some honest talk about the weird process of blurbing

[Note: This article is about blurbs—quotes of praise that appear on book covers—a somewhat inside baseball topic. Please feel free to skip if the topic doesn’t interest you.]

Blurbs. Can’t live with them, can’t live a luminous tour-de-force life of tender-hearted lyricism and soul-nourishing honesty without them.

Or maybe you can? Last week, Sean Manning (publisher of Simon & Schuster’s titular imprint) published an article in Publishers Weekly declaring that the imprint will no longer require blurbs:

In no other artistic industry is this common. How often does a blurb from a filmmaker appear on another filmmaker’s movie poster? […] The argument has always been that this is what makes the book business so special: the collegiality of authors and their willingness to support one another. I disagree. I believe the insistence on blurbs has become incredibly damaging to what should be our industry’s ultimate goal: producing books of the highest possible quality.

Although it is a bit unclear exactly what will change—the article notes S&S never had a formal blurb policy and that they will still happily publish the blurbs they get—the article set off stunning and sui generis round of page-turning applause on literary social media. Blurbs are something few people love. As Manning says, blurbs take up everyone’s time. The writer, editor, and agent tend to all spend precious hours writing request letters to potential blurbers and following up as deadlines approach. For the blurbers, requests quickly pile up and—at least if you read the books you blurb—take a lot of time to complete. Readers have long been annoyed by the hyperbolic language of blurbs. Here’s George Orwell in the 1930s discussing how readers are turned off by “the disgusting tripe that is written by the blurb-reviewers”: Novels are being shot at you at the rate of fifteen a day, and every one of them an unforgettable masterpiece which you imperil your soul by missing.

If they take up everyone’s time and everyone hates them, why do blurbs persist?

I too have blurb complaints, although I tend to find the discussion around them somewhat disingenuous. I’ve seen many anti-blurb takes over the years that were from bestselling and/or award-winning authors who, having reached a place where blurbs no longer helped their career, decided the practice should end. Those can feel a bit “pulling the ladder up behind you.” What’s refreshing about Manning’s article is that it was written by a publisher who is actually in a position to change things.

Still, I remain skeptical that blurbing will disappear anytime soon because I think the answer to the question of why blurbing is so common is that, well, blurbs work. And in some ways blurbs are more necessary than ever.

Before I dive into that, let me offer a little praise for blurbs. Yes, asking for blurbs and writing them are both stressful in many ways. I know no one who enjoys the process. But there can be something lovely about blurbing. As a blurber, it is nice to help an emerging writer’s book and offer encouragement in a very hard career path. And as a blurb receiver, what is better than seeing your work praised by an author you admire? People dismiss blurbs as merely being about connections, but that not true of all blurbs. I have blurbed mostly authors I didn’t know and have received blurbs from authors who didn’t know me. It is in some ways a nice part of publishing.

Of course, in other ways blurbs are stressful and irritating and hard to get right. If you send too many requests, you may end up with too many blurbs and hurt feelings when you have to leave some authors off the cover. If you send too few requests (or too many authors turn you down), you may be left scrambling and begging as your deadline approaches. Add in all the fair critiques of cronyism, connections, and hyperbolic language and it is easy to see why many (even most?) people in publishing would be happy for them to disappear entirely.

So why do I say blurbs work and may be more necessary than ever? Because the brutal math of publishing hasn’t changed.

The brutal math of publishing is that there are far more books published than there are readers to support them, book review spots to cover them, or shelf space in bookstores to sell them. Blurbs are one way to help everyone sort out which books to pay attention to. Blurbs aren’t necessarily for readers browsing a bookstore, although I’ve known readers who buy based on blurbs. They are more important behind the scenes. Blurbs are frequently used in publicity pitches to book reviewers—ETA that while editing this I got two publicity emails and both subject lines quoted blurbs. Booksellers have told me they’re useful for figuring out which books to buy and where to place them in the store. (Ironically, one bookseller told me that big imprints like S&S—that publish a variety of books in different genres and ranging from literary to commercial—are exactly where blurbs are useful for booksellers trying to sort through new titles.)

Let’s make a distinction here too. There are two types of blurbs: “author blurbs” requested before publication and “press blurbs” culled from reviews and/or media coverage. These may differ in origin but are identical in function and often language. (Orwell was critiquing press blurbs in the quote above.) I can’t say for certain how much blurbs help sales, but many industries seem to think they’re important. Sure, movie posters and film trailers don’t typically have quotes from other directors…but they certainly use press blurbs. The reason film posters and movie trailers can include press blurbs and book covers can’t is logistical. Book covers are sent to the printer months before most book reviews come out. Film trailers can be quickly recut as press comes in while books need to wait for a second printing—which many books never get—to change the cover. This seems more a question of production than “collegiality.”

(We could add that other artforms do similar “collegial” promotion too. Hollywood films are often promoted by “names” signed on as producers who may do no real work on the project. Big musicians help smaller musicians by guest starring on albums and touring with each other. Etc.)

It might be preferrable if we could replace all author blurbs with press blurbs. Reviews are, at least in theory, less prone to cronyism and hyperbole. But this would require a complete reorganization of how book production and publicity works. And anyway the rapid decline of professional review space and increasing number of books means that wouldn’t help the majority of books anyway.

Maybe policies like this new S&S one will decrease the importance of blurbs. It’s also quite possible—given that they say they’ll still happily publish blurbs that come in—the result will be minimal blurb outreach for non-famous, non-connected authors while the famous and connected authors get their blurbs as usual.

I have to stress again that there is a near unending stream of books published and everyone—reviewers, readers, booksellers, etc.—needs some way to winnow them down. No one can read a million forthcoming books each year. The math demands that we all figure out shortcuts, which will never be fair. Few love the incestuous and network-y nature of blurbs, though the alternatives aren’t much better. Most of what determines success in publishing is what determines success for anything in America: money. Both the money publishers spend marketing and publicizing a book and the money authors themselves shell out to promote their books. Is being able to spend five figures on an independent publicist a “fairer” way to promote a book? Or having your publisher buy ads in glossy magazines or use connections get magazine profiles?

Another major thing that determines success in publishing as in life: fame. Manning says, “In fact, several of our recent bestsellers have been blurb-less—Down the Drain, Sociopath, Dinner for Vampires—proving that readers don’t need the shorthand of blurbs to find great books; they can be trusted to judge quality for themselves.” But Down the Drain was written by international celebrity Julia Fox and Dinner for Vampires by TV actor Bethany Joy Lenz. I saw a famous journalist share the PW article and say they wrote a bestseller without blurbs—though in fact their back cover was 100% blurbs pulled from press coverage of their career. Nothing wrong with that. But the fact that celebrities can sell books without blurbs and famous journalists can cull press quotes from years of media coverage doesn’t really tell us anything about what an unknown memoirist or midlister novelist or a debut short story collection writer can do.

Still, it would be good if there was less emphasis on blurbs. I would be thrilled if Manning’s stance helps decrease their importance and everyone’s workload. And I do think there are some steps that could make blurbing more bearable for everyone involved without hurting the chances for smaller books and unknown authors. Here are a few quick suggestions:

End blurb inflation (3-6 max per book). In recent years, I’ve seen publicity emails for buzzy books that included 10 (or 12 or more!) blurbs. This is… too much. You can’t fit that many on a book cover and whatever function blurbs serve for positioning or buzz can surely be filled with just a handful. Requesting that many blurbs also makes it harder for every other author—especially the less connected—by taking up what blurb time established authors can set aside. 3-6 seems like as many blurbs as a book could need.

No more proposal / unsold manuscript blurbs. It has become increasingly common to ask for blurbs for manuscripts that haven’t yet sold and may never come out. I get it. Selling books is very hard. But like the aforementioned blurb inflation, this taxes the whole system unnecessarily. Anyone famous enough that their endorsement would actually move the needle for a publishing house is surely overwhelmed with blurb requests already. And how can one honestly blurb a proposal for an unwritten book or an unsold manuscript that may go through dramatic revisions and be unrecognizable by the time it is published?

Once you’re famous, no more blurb requests. There is no reason a bestselling, award-winning writer needs blurbs for their new book. “Pulitzer Prize Winning Author” and triumphant praise for past work from major newspapers are going to do more to sell books than praise from colleagues. Save the blurbs for the midlisters and debuts.

Okay, that’s about all I have to say about blurbs. If you made it this far, check out my forthcoming novel, Metallic Realms. It’s pretty good! If you don’t trust me, well, it has some amazing blurbs…

If you enjoy this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout—which The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent”—or preorder my forthcoming weird-satirical-science-autofiction novel Metallic Realms.

Great piece. My blurber rule as an editor is: ideally, you want one huge name and/or three very good names plus one or two more good names. Basically, your list of blurbs should be like the talent on a top NBA team. Together, their blurbs should let you tell the story of the book without having to resort to copy.