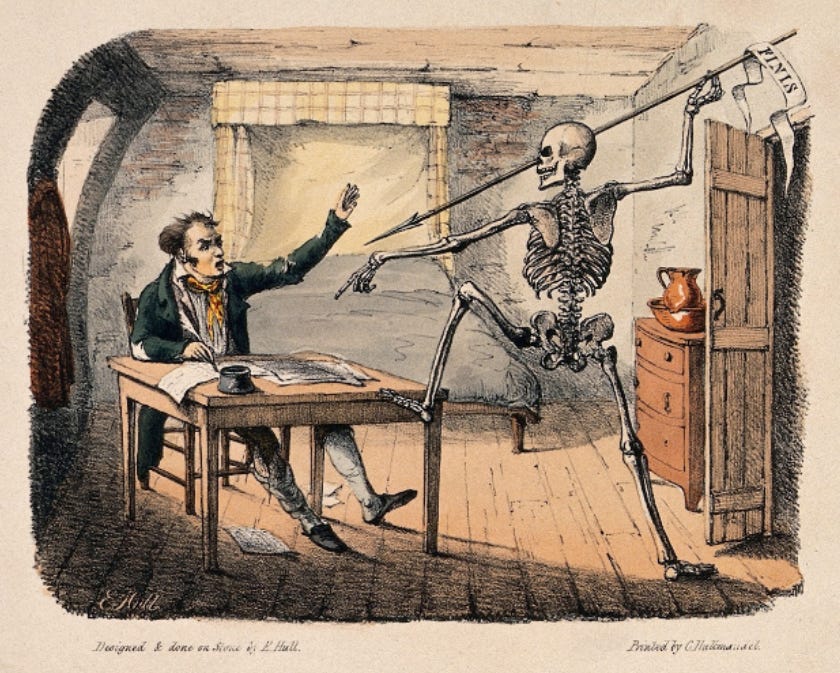

Y'all Wanna See a Death of the Author Body?

On the ways the corpse of the author is being bent out of shape

Recently, I came across a post that feels so perfect I had to share. It’s from Tumblr user prokopetz (and I initially saw it shared by Nick Mamatas so hat tip there):

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Counter Craft to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.