Why You Should Still Build Your Raft of Art in the Sea of Slop

A little cri du coeur about working on your work and avoiding all the noise

Before I get to this week’s newsletter, my good friend —a brilliant writer and two-time Pulitzer finalist (in feature writing and memoir)—just started a Substack. First, you should subscribe! Second, she told me I should be less hesitant to remind you, my dear readers, that I put a lot of time and effort into this and paid subscriptions allow me to devote even more time and effort to Counter Craft. “You can blame it on me,” she said. So, there you have it. I really appreciate paid subscriptions. (Buying my novel is also very appreciated.) You can blame Chloé for me saying so. Just kidding. But do check out her newsletter.

Recently, a reader restacked my “Art in the Age of Slop” article about making art in an age dominated by both human and AI-generated slop. They expressed the feeling that it just sucks ass to be an artist in 2025. (They didn’t curse, I’m paraphrasing.) Why even bother making art when everything is controlled by corporate algorithms that suck up all the profits? Why waste your days honing a craft when plagiarists, sloppers, and scammers get ahead? Why share your art only to get tech bros with NFT avatars shouting “AI will render you snobby artists obsolete in a year!”? What’s the point of making something unique when all anyone cares about is generic garbage? (And that is not even getting into the state of the country, the ongoing wars and horrors around the world, or the looming threat of climate change.)

Perhaps these are familiar thoughts for you too. I’ve certainly felt them. So, I thought I would try to write something a little more positive about why there is still a lot of value of making your own little raft of art in the sea of slop. Why it is worth it to work, create, and share your art.

For the purposes of this article, I’m going to assume that you are someone who wants to make art—however you might define that. If you are a writer, that you want to make literature, in whatever genre or style. That you want to make books that could never be output by algorithms or corporate franchises nor be tailored to social media hashtags and trope checklists. Work that is strange and interesting and beautiful and above all unique to you. If so, here is what I remind myself when I’m depressed about bestselling dreck or algorithmic slop or declining literacy of the country or any of that noise: that crap has jack shit to do with you or your art.

It has nothing to do with you! Nothing. It is completely irrelevant to what you are trying to do. It doesn’t matter. Don’t waste your time on it.

I don’t merely mean that it is irrelevant merely in the sense that stressing about artist-hating AI bros or pop culture nonsense won’t help you improve your sentences or revise your novel-in-progress—although that’s certainly true. The more time we spend stressing and scrolling, the less time we have to engage in the art we love or work on our own artistic practice. But I also mean that those people are doing something completely different than you are trying to do. Yes, a hashtag-tailored/written-by-committee bestselling novel and Moby-Dick are technically both “books.” But only in the same way that the ExxonMobil corporate logo and Guernica are both “works of visual art” or that microwaving a frozen burrito and preparing a meal from scratch are “cooking dinner.”

I’m not saying that you can’t enjoy an airport novel or a microwaved burrito or the design of a corporate logo. They all have their place. I’m saying that your art is no more in competition with such content than it is with Candy Crush, bad reality TV, or social media doom scrolling. Yes, in an abstract sense there are a finite number of humans each with a finite amount of time in their lives. It does not follow that a statistically significant number of people are going into a bookstore and thinking, “Hmm, do I buy my 25th commercial thriller by James Patterson or this experimental work by an author I’ve never heard of?” The readers of your work are different readers. Your work was never going to appeal to all or even most people, not even if you were the reincarnation of Tolstoy or Toni Morrison. The AI evangelists with NFT avatars who tweet about wanting to eliminate artists weren’t ever going to read your work. The people who only care about multimedia corporate franchise “universes” or who simply have interests other than reading weren’t going to either. So why bother worrying about what they do with their time? You don’t need to think about that.

I know that the algorithms and corporate platforms of our social media age work overtime to make us think we are required to pay attention to every big budget reboot or celebrity scandal or corporate advertisement (looking at you, American Eagle blue jeans ad discourse). But we don’t. We just don’t.

When I was growing up as a weird and alienated and bored kid in central Virginia, art was my portal into a larger world. At first, that was science fiction and fantasy books. When I was a little older, it was punk music that led me to underground hip-hop, stoner metal, weird fiction, Surrealism and Dadaism, independent literary presses, foreign cult films, and a host of other interesting and mind-expanding things for little weird teen Lincoln. These works of art meant everything to me. A few of them, like say Twin Peaks or David Bowie, were very popular. Most were not. But the absolute last thing I cared about was what other people were reading and watching. What did I care if they were listening exclusively to top 40 radio and never ventured outside the bestseller list? Or if they never read or listened to music at all? That was their loss. And anyway, it had jack shit to do with me and my inner life.

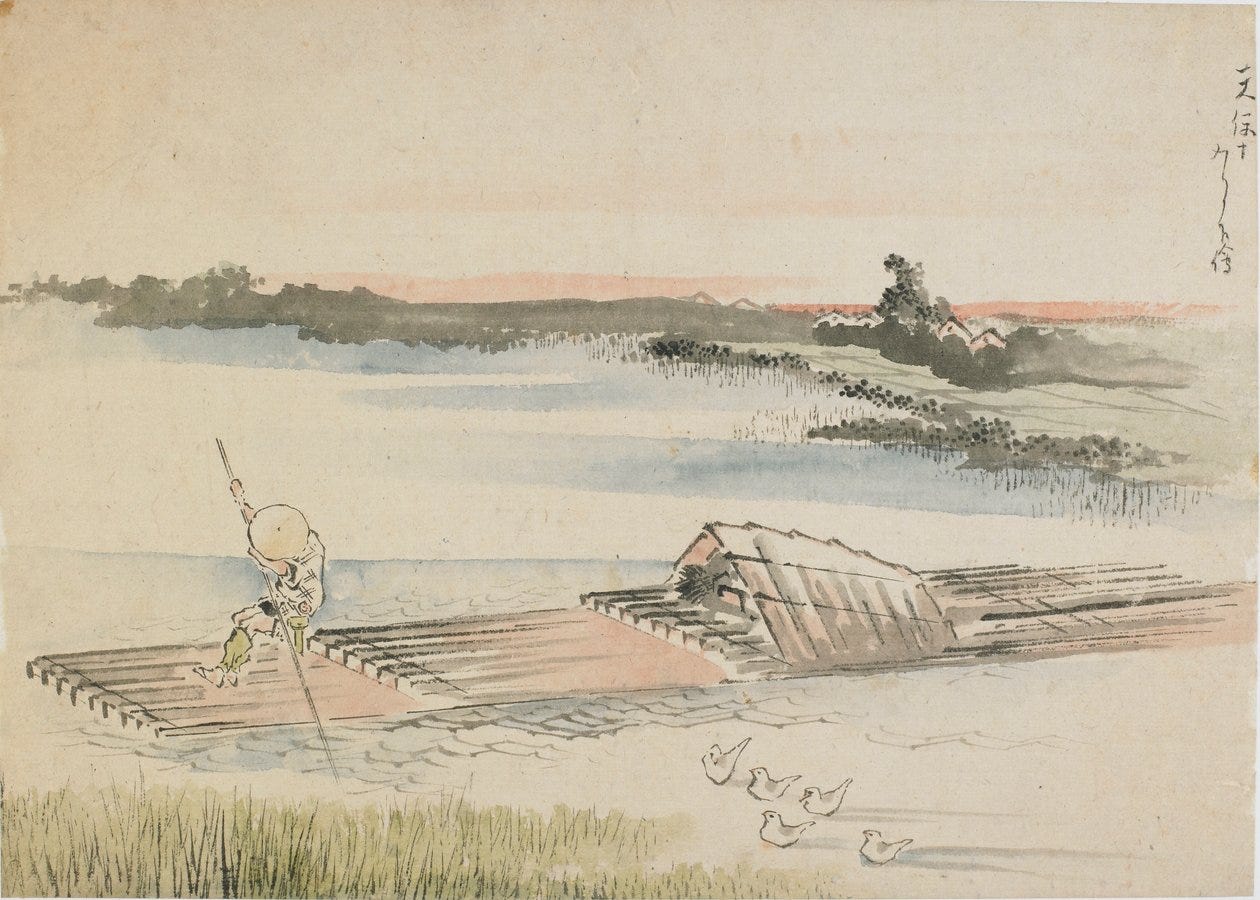

The art I cared about and immersed myself in was my own little raft. My place to be alone. It allowed me to float above the slop and not worry about whatever sloshed around in the mainstream mass. Your artistic interests were likely different than mine growing up. Still, I bet you were a lot more concerned with what moved you than what other people spent their time on. Right? Why worry about it now.

I don’t mean that I was the kind of person obsessed with obscurity who rejected artists once they became popular. (“Everything sucks after their first EP!” used to be the joke in punk circles.) Quite the opposite. I’ve always been a proselytizer for the work I love, which anyone who reads this newsletter knows. I want people to enjoy the art that moves me… but only if they will enjoy it. If they don’t, oh well. None of my business. And I certainly won’t let their disinterest dull my interest.

When I decided to be a writer, I always expected my work would be weird shit that was unlikely to top the bestseller list. Few of my idols ever did, after all. This is not to say I’m especially humble or have cleansed my ego to reach artistic enlightenment. Certainly I want awards, acclaim, and all the rest. (Mostly I want money so I can quit doing every other job and have more time to write. I’ll get to that in a bit.)

But it is useful to remember that art and literature—and especially good art and good literature—have more or less always been of moderate or marginal interest to the general population. The majority of people do not go to a play, gallery, or dance performance in a year. While writing this, a pair of Substack notes came through my feed pointing out that only 54% of the US population reads one book a year… but also in the supposed literary glory age of the 1950s only 39% of the population managed one book. One single book. Most of those single books were probably self-help or business insight guides. The percentage reading a novel or a memoir or a poetry collection—even a bad one—is small. It just is. This is why in my article on the recent “decline of literary fiction” discourse, I pointed out that the bestselling literary books of the past were both rare and the products of unique circumstances. That’s just how it is. C’est la vie.

I’ve always found it a little silly how much literary discourse revolves around the number of “books” sold or read, as if that has anything to do with us trying to make literature. Books are a broad and nebulous category. A decade ago, many novelists and poets were giddy about the increase in print book sales—that was caused by a boom in “adult coloring books.” I don’t care one way or the other about adult coloring books. Color whatever you want. But what did they have to do with good novels? Nothing. Sales of coloring books are not gateway drugs to mainlining complex systems novels. An increase in celebrity memoir sales doesn’t benefit innovative science fiction. A spike in Sudoku puzzle books doesn’t correlate with a boom in lyric essays. If you work in publishing, yes, overall sales matters. If you are an author of other kinds of books, then that all has nothing to do with you. Don’t worry about it.

And let us remember that ages past were not as different as many pretend. Jane Austen sold relatively well in her day, but that was back when novels were published in editions of a couple hundred and read almost exclusively by landed gentry. Even Shakespeare’s plays were overshadowed by the truly popular entertainment of the day: watching dogs maul chained bears. (Did Shakespeare get stressed about the pointlessness of writing sonnets in an age dominated by bear baiting? Maybe. But I’d like to think he thought, that shit doesn’t have anything to do with what I’m doing.)

Perhaps our modern age of endless superhero reboots, reality dating shows, and movies based on toys is a more enlightened time than Shakespeare’s. The fact remains that great art is never going to appeal to everyone. Even if you want to point out unique times and places when specific art forms were more renumerated and respected, well, so what? There is no time machine. You cannot transport yourself to the 1960s Greenwich Village any more than the theatres of ancient Greece performing Aeschylus. You are only here, now, with the brain you have and the times you live in. All that other shit has nothing to do with what you are doing.

We all must ask ourselves what it is we want to do with our time on this planet. Do you want to make something beautiful and true and unique to you? Or do you want to make something formulaic, trend-chasing, and interchangeable because “the market” is says the ROI might be better? You can choose to compete with books written by committee and tailored to “TikTok hashtags”, brand-name authors who farm out the actual writing to ghostwriters, and writers who leave ChatGPT prompts to “rewrite in the style of [another author]” in their published books. There is money there. There is. But there is also lots of competition—and the more formulaic your work, the more likely AI can automate it—and so there is about as good a chance you will fail going down that route as there is writing something unique.

What about the work that may be in some way competing with yours? Mostly, you won’t know. You just won’t know when similar books are being queried to the same agents or submitted to the same publishers. So, it is again best to not think about it. When those books are published, the healthiest attitude is to be excited if they get attention because that means more people might find your work. This is true, or at least more true than the idea your novel will be benefit from sales of adult coloring books.

Don’t get me wrong. Money matters. Being able to pay rent and afford to give yourself the time and space to make art matters. Artists live in the world and have to think about these things. There are no easy answers. All I can say is that, firstly, is useful to have a realistic perspective. This is why I dedicate a lot of this newsletter to publishing demystification. It is healthy to approach any artistic career with open eyes. The writers I know who have been driven mad by the industry are those whose expectations were untethered to reality. Secondly, it is useful to separate the business side of publishing from the artistic side. I mean that both in actual practice—e.g., do your business work at different hours than you create—and in your mentality. Sales aren’t art. Virality isn’t beauty. Publishing isn’t literature. These things only intersect intermittingly.

So let me dispense with talk of sales and markets. Why make art in an age—like most ages—in which few care about it? Make art because making art enriches your life in ways other than money. Practicing an art form changes you and enlarges you. It makes you look closer at the world, think deeper, live better. I know this is corny to say. Every now and then the corny is the true. I’m not saying art is the only way enlarge your life. Friends, family, and love are other good options. Philosophy and certain drugs too. Art is definitely one way though, and thankfully these are all non-exclusive.

(This is also why I think authors should be very careful about using GenAI in their actual creative work. If you can integrate it thoughtfully into an artistic practice, okay. But if you are using it as a shortcut and outsourcing parts of your creativity to computer programs, then you will be degrading your own abilities and impoverishing your own vision.)

I’ve always rolled my eyes at writers who say you should never write unless you can do nothing else with your life. That art is a misery and being an artist a punishment from the gods. I think that is corny and untrue. What is true, though, is that you should only write (or paint or photograph or act, etc.) if you love it. If you enjoy the act of creation. If you get satisfaction from wrestling with words and shaping sentences and producing paragraphs. If you do not enjoy it, don’t bother. There are many other things to do in life. And many easier ways to make a living. The joy—or at least a joy—in being an artist must be in making the art, even if no one else even sees it.

I don’t talk about my personal life too much on here. But I will say one thing. My wife and I just had a little baby girl. She is wonderful and strange and overwhelming and all of the things you read about in books before experiencing in real life. When we went to get our first ultrasound, her little hummingbird heartbeat reverberated through my whole world. My wife had to go to work after. I walked around in a daze and then sat alone on a bench in the park. I had a notebook with me. I wrote something, a poem, because I am a writer and sentences are how I see and make sense of the world. I’d forgotten about that poem. Recently, I was going through an old notebook and found it, read it, and let all of those beautiful and confused feelings rushed back, all carried in those words.

The poem was not so bad. I won’t publish it here. Or anywhere. Maybe I’ll be able to give it to my daughter when she is older. Maybe it will mean a lot to her. Maybe not. But it meant a lot to me.

I am not terribly optimistic about the state of the world. I do not think the people with power and wealth are working to improve our lives. In the realm of art, I think they are trying to drown us in their flood of garbage until we are hollowed out automatons with no function left but to consume “content.” Yet isn’t that all the more reason to make your own little raft of art? A practice and a place where you can float above the slop and engage in what moves you, enriches you, and enlarges you?

All that other stuff, well, it has nothing to do with what you are doing.

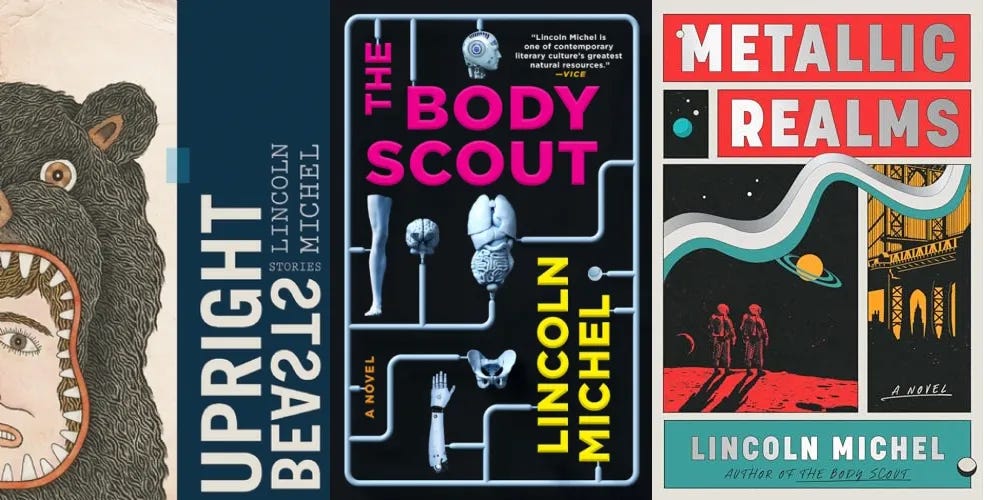

My new novel Metallic Realms is out in stores! Reviews have called the book “Brilliant” (Esquire), “riveting” (Publishers Weekly), “hilariously clever” (Elle), “a total blast” (Chicago Tribune), “unrelentingly smart and inventive” (Locus), and “just plain wonderful” (Booklist). My previous books are the science fiction noir novel The Body Scout and the genre-bending story collection Upright Beasts. If you enjoy this newsletter, perhaps you’ll enjoy one or more of those books too.

I believe your great advice goes to those who want to make a *living* in art. Someone that only wants to make art--let the world be damned--does not care about slop, "content," or garbage.

My guess is, however, that the original artists made art to order. The king commissions a mural, so you paint one. Towns feed poets, and so you become Homer. Yours is a trade like anybody else's. If this is true, those who work for Disney today may actually be the true heirs to the original artists.

Next came those who made art but did not need the income. Your Jane Austen, for example. But really most anybody; if not landed gentry, you'd be at least a lawyer or a flourishing printer.

Then came--and quite recently--the idea of being true to your genius *and* being paid for that. Well, how is that supposed to happen?

Very simple. The same way you become Napoleon. All you have to do is, be one of the 10,000 adventurers who went into the soldiering business that year. Next, you only have to be the last one standing after the others all get finished off. Isn't this sort of how it works? (It's a real question because I don't know.)

Unless you are truly exceptional (as you, Lincoln Michael, are), isn't it simply madness to try to be a paid artist?

Congratulations on your baby girl!

“…her little hummingbird heartbeat reverberated through my whole world.” is the purest sentence I’ve read today. Anyone who has been there can relate. Just magical.