When Will Novels Fix Society Already?

Fiction can help us understand our world, but that doesn't mean novels can solve our problems.

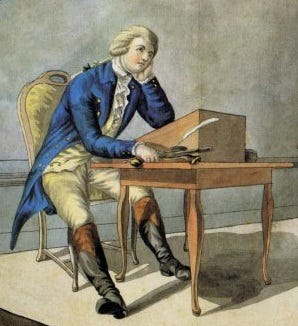

In the 18th-century, a specter was haunting Europe—the specter of “Werther Fever.” Goethe’s 1774 epistolary novel, The Sorrows of Young Werther, was so popular that it catapulted the young Goethe into international fame and set off a trend of young men wearing yellow trousers and electric blue jackets… and also, allegedly, thousa…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Counter Craft to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.