What Algorithms Can't Tell You about Art

On Prosecraft and why data analysis of fiction rarely says anything at all

Today, my social media feeds have been filled with authors upset about Prosecraft, a website from a software company called Shaxpir (yes pronounced Shakespeare) that claims to use A.I. to analyze novels. As far as I can tell, the company is minor and the project probably got little attention before today. Their blog hasn’t been updated since 2019. That isn’t to say authors are wrong to be upset. Prosecraft clearly used authors works without permission or payment. I found plenty of 2023 novels on the site, so even if the blog is defunct someone is still updating it.

The creator has so far offered a rather weak defense saying “The only purpose of this project is to serve the community of authors, whose works I cherish,” and offering up an email address for authors to request removal. Was the purpose of Prosecraft was not to “serve the community of authors” or to promote a feature in the software that Shaxpir sells, as they implied in the explanation page?

(EDITING TO ADD: since I posted this newsletter, Shaxpir has apologized and announced they’re taking Prosecraft down. See note at the bottom.)

Plenty of people have covered the copyright issues and ethics questions. But what stood out to me was just… how dumb the analysis is. Every now and then a tech company or “data analysis” group comes out with tools that claim to explain art yet never end up saying anything useful at all.

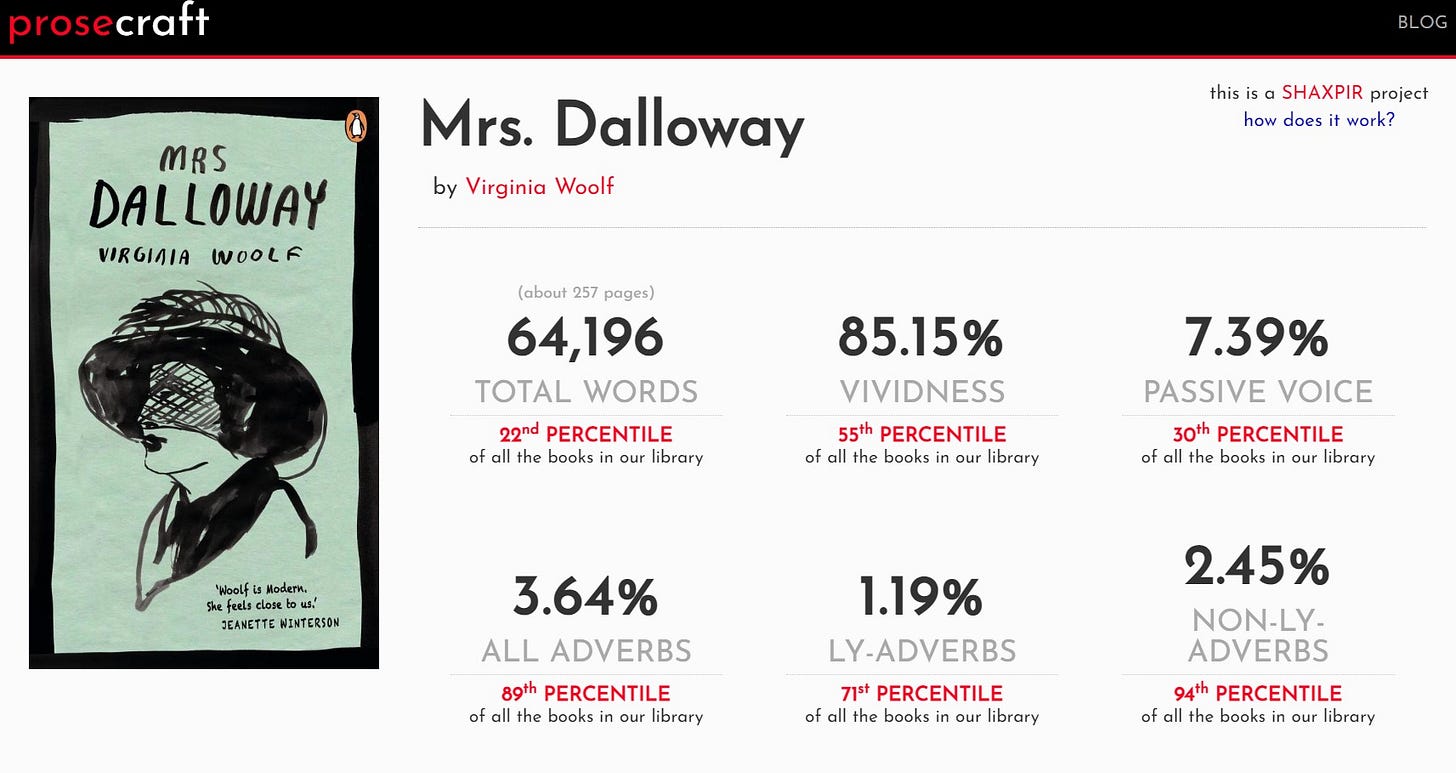

Prosecraft claims to rank literature based on qualities like “vividness” and “passive voice,” producing “analysis” of a novel that looks like this:

Trying to rank literature by simplistic qualities is already antithetical to understanding art, but even worse are these specific categories. What human reads a novel thinking consciously or unconsciously about the percent use of passive voice? What am I supposed to take away from hearing Virginia Woolf is in the 55% percentile of vividness? And why is Prosecraft so concerned with adverbs? They’re 50% of the analysis!

(I’ve written before about how the the problem with using adverbs isn’t the existence of them. The problem is that most writes use redundant adverbs that don’t complicate the verb. If your adverbs complicate the verb, they can be useful. “She smiled happily” vs. “She smiled angrily.” )

The data analysis is even more absurd than it seems on the surface when you read how these categories are calculated. The most embarrassing is “passive voice,” which the creators literally don’t understand. They “measure the total number of helping verbs (be, am, is, are, was, were, etc),” but many active voice sentences use those verbs and their examples include numerous active voice sentences. Whoops.

“Vividness” has a more a complex analysis, though no less sillier. They define vividness as “invok[ing] a sensory experience” and claim to have assigned nouns, verbs, and adjectives “vivid” points and then count up the points. Here’s their example: “the word “dewdrop” has a vividness score of 9.5, and the word “eyelash” has a score of 6.3.” Why is dewdrop 3.2 points more vivid than eyelash? There’s no explanation.

How vivid a single noun is surely varies from reader to reader with the individual connotations. But even if there was a way to prove that “rock” is more vivid than “stone” in some objective sense this doesn’t help us understand how vivid prose is. Prose is not individual words. It’s sentences that are part of paragraphs that are part of a larger narrative. A good work of fiction has everything working together to create specific effects. E.g., the exact same text may become more vivid—may conjure more imagery in the reader’s mind—if given more paragraph breaks since that makes most readers slow down and absorb each sentence. Cramming the passage into a long paragraph produces different effects. None of this is calculated with assigning words vivid points.

Vividness, or any other quality, isn’t about individual words but the impossibly complex web of meaning constructed both in the text itself and in the cultural context a text is produced. As well as what the individual reader brings to the table of course. Tone, mood, narrative, allusion, voice. All of these affect whether using “rock” is more vivid than “stone” in a specific story. “Is blue more vivid than red?” isn’t how an artist thinks. An artist thinks something more like “Will making this character’s coat blue evoke the ocean motif I’ve woven through the story? Will using red strengthen the Little Red Rodding Hood allusion in this fairy tale?” There are endless calculations like this, most made subconsciously perhaps, in creating a work of art.

All computer analyses of art seem to turn out this way. Random points assigned to a flawed metric that thinks you can understand the forest by computing the “leaf points” of each tree.

It reminds me of a “data analysis” from a few years ago that got fawning media coverage for “revealing the six emotional arcs of all fiction.” The analysis counted up how often stories used “positive” or “negative” words—again, not really how art works—using a similar point system to the vividness calculation above. Then it claimed to “reveal” that all stories have one of six emotional arcs:

A steady, ongoing rise in emotional valence, as in a rags-to-riches story such as Alice’s Adventures Underground by Lewis Carroll. A steady ongoing fall in emotional valence, as in a tragedy such as Romeo and Juliet. A fall then a rise, such as the man-in-a-hole story, discussed by Vonnegut. A rise then a fall, such as the Greek myth of Icarus. Rise-fall-rise, such as Cinderella. Fall-rise-fall, such as Oedipus.

[…]

Of course, many books follow more complex arcs at more fine-grained resolution.

First, the emotional arcs of stories surely have more going on than “rise or fall.” There are more than two emotions. And these specific examples expose how simplistic the analysis was. Surely Romeo and Juliet certainly has a rise before the fall!

But even more absurd is that these are literally the only possible outcomes based on the parameters. If you define all stories as having 1 to 3 total emotional trajectories and the only trajectories as “rise” and “fall” then all you can possibly have is R, F, RF, FR, RFR, and FRF.

It’s a lot of computational power to say nothing at all.

Surely there are useful ways to use data to analyze literature. But I think these projects doom themselves from the start by trying to “solve” art. To find the right percentage of nouns or prove the # of plots.

Of course, it’s hard not to think about this in the context of the current tech hype around “A.I.” writing programs. Indeed, Shaxpir frames their work as “A.I.” although even as an A.I. skeptic I’m not sure counting up the number of adverbs in a text = artificial intelligence.

But one of the reasons I remain skeptical about the abilities of A.I. programs to create art is that the real work of fiction is in the details. Its in creating those tiny connections between words, in minor adjustments of pacing and scene, etc. It’s in all the things that these algorithms and data analyses can’t compute.

The last few weeks I’ve been working on short stories and logging my hours for my accountability. Doing so reminded me that the majority of time I spend on a story is not getting a first draft down, the part that an A.I. program is most equipped to help with. The time is in the revision. The refinement. For each hour I spend getting 90% of a story down, I’m going to spend spend many times that revising that last 10%. Reading it over and over making adjustments both to the lines, paragraphs, and scenes. Weaving through connections and meaning.

The real work of art isn’t in choosing to use “dewdrop” or “eyelash.” Its in making “dewdrop” or “eyelash” powerful in a specific sentence in a specific story. And then doing that again and again and again and again and again…

UPDATE 4:40pm: In the minutes since I posted this initially, Shaxpir has announced they’re taking down Prosecraft due to the outcry from authors. The creator seems legitimately contrite and I fully believe he didn’t make much money from it. I still find the Prosecraft analysis unilluminating for the reasons above, but I don’t think he had evil intentions.

UPDATE 4:50pm: That said, the explanation of how the texts were found is a bit unsatisfying in the apology post. “I only ever incorporated books that were published publicly, and whose text could easily be found by crawling the internet. If someone could write a wikipedia article about the plot and characters of a book, I reasoned that I could publish linguistic summary stats in the same spirit.” Recently published novels do not have their entire text on the internet unless it is on illegal pirate sites, which should have been a hint that perhaps this wasn’t above board. Hard to compare that to writing a short wikipedia plot summary.

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.”

Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

Shaxpir? Lol. With that adverb/vividness/etc breakdown, should've gone with Wyrdzwyrth.

On a related note, I have a Google alert set to inform me whenever my name appears on the internet or in the news. Ninety percent of the time the alert is for a pirated copy of one of my books that's available for download.