To Understand What Books Are Published, You Must Understand How Books Are Sold

Plus cyborg baseball and the Anthropic AI author settlement info

Baseball and Cyborgs

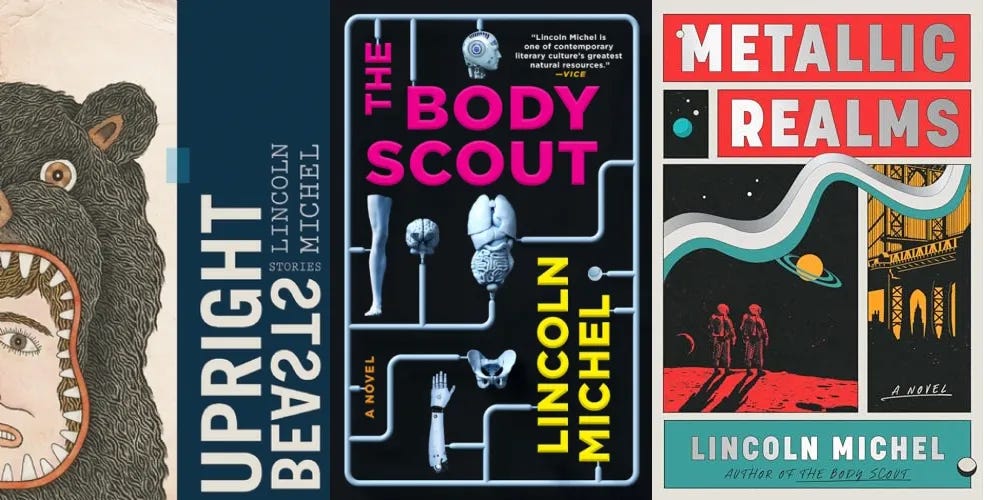

It’s the MLB postseason, which means I might as well plug my science fiction noir novel The Body Scout that involves a future baseball league run by biotech companies to advertise their body-altering products. Yes, you could call it dystopian. If you like baseball and science fiction, you might enjoy! Although plenty of readers who don’t care about baseball loved it too. As long as I’m plugging my work, it’s also a great time to check out my new novel Metallic Realms. If you have read and enjoyed either novel, it’s always helpful to leave a review on Goodreads, Amazon, or Barnes & Noble.

Okay, end of plugging.

Make the Robots Pay: Anthropic AI Author Settlement

PSA for authors: the Anthropic AI settlement website is up and has a searchable database of included books. If your book appears, then file a claim to get some money. Allegedly, it will be $3,000 per book split between the publisher and author(s). Who knows what the actual number will be when all is said and done. Still, it is worth filing a claim to make the robot overlords pay.

Note: I’ve seen a lot of authors asking why books that were on The Atlantic’s LibGen dataset aren’t included in the settlement. There are a few possible reasons—such as the publisher’s failure to file a copyright—but the big one is that The Atlantic’s dataset was from 2025 while Anthropic (allegedly) stopped downloading from LibGen in July 2021. So, no books published after that are included.

To Understand What Books Are Published, You Must Understand How Books Are Sold

The reason “Publishing Demystification” is one of my main topics on Counter Craft is that I find many authors are unaware of how publishing actually works, and much of the literary discourse is based on erroneous ideas about the reality of publishing. I include myself here. As a younger author, I really didn’t understand the nuts and bolts of publishing much less how those bolts and nuts determine how the entire machine runs. And I really only know more now because I’m friends with people on the publishing side and ask them questions.

I think it is good for one’s mental health as a writer to understand the business. This isn’t because I want people to write “for the market” or look up “writing hacks” to earn more money for less work. I’m a writer and reader of weird books that are unlikely to be bestsellers. I care about art. But, that’s all the more reason I think having realistic expectations is useful.

One thing writers should understand is how publishers sell books. Publishers do not sell books to readers per se. They sell to accounts. Accounts are retailers, from small indie bookstores to huge places like Amazon and Costco, but also book clubs, subscription boxes, and libraries. Everyone knows this abstractly, but they sometimes don’t think through what that means in practical terms. For example, it is common to hear people—especially self-pub enthusiasts—claim that publishers “steal 90% of the cover price from the author!” because royalty rates are around 10%. But publishers don’t get 90% of the cover price. About half the cover price of a book goes to the retailer, and another chunk goes to the distributor.

But accounts don’t just affect the selling side of books. They also affect acquisitions and can even influence the design. Hate your book cover? Confused as to why your publisher is insisting on a title change late in the process? It might be because big accounts told the sales team they hated the cover or title and would only increase their buy if those were changed. (This is more common for commercial fiction than literary fiction, because, well, the Walmarts and Targets of the world only stock the former.)

The publication of a book involves not just editorial decisions but also sales and marketing ones, which both involve feedback from accounts. Book clubs will pick a book well before its publication. Retailers make their initial buys before a book is even printed so that a publisher prints (approximately) the correct number of books. And it is these forces and decisions that determine which books go on display in windows or get stacked on “New Release” tables that in turn affect what books are purchased by readers. Retailers will adjust things as sales and reviews come in, and books can bomb expectations or become surprise successes. Still, a depressing truth of publishing is that much of the success of a book is determined long before readers ever get their hands on a copy.

(Again, I am simply explaining the process. I am not saying it is ideal.)

I wrote about the way the Book Club Industrial Complex shapes what books are acquired in my last newsletter. Another example of how accounts shape publishing, for good or ill, is when it comes to two of authors’ most hated things: track and comps.

Nuts and Bolts of Track and Comps

Recently, there has been a lot of publishing discourse spinning off of Tajja Isen’s Walrus article about the state of publishing. It’s a good if bleak article that I recommended in my last newsletter. A central point is that publishing focuses a lot on “track”—aka how many copies an author’s previous books sold—which warps what books get acquired. Publishers focus a lot on debuts, because debut authors have no track. “Nothing but potential,” writer and researcher Laura McGrath is quoted as saying. “If your track is zero, there’s only one place for it to go.” On the other hand, if your debut isn’t a huge seller then it is much harder to sell the next book because the “track” hangs around your neck like an albatross. A book that sold poorly, perhaps for reasons beyond the author’s control, can kill a career.

No matter the reasons for the flop—a tiny marketing budget, staff turnover at the press, cutbacks in culture coverage, backlash toward a hot literary trend—the writer carries the failure on their record.

To say something more hopeful here, one editor told me that it is good to remember publishing is a narrative business. It is the job of the agent and the editor to spin a narrative about why the new book will be different. “The last novel came out during COVID lockdown, but the new novel is in a different genre and the author will be on a ten-stop tour for live events!” Authors do sell books despite poor track records, at least sometimes. Obviously, the ability to spin a narrative depends on the book and the circumstances. It is easier to spin a totally new project as having potential than it is to spin, say, book three of an unpopular series. If no one bought the first two books, how many will buy the third?

A lot of this comes down to accounts. I mentioned this briefly in my last newsletter, but I want to recommend two great Substack articles that explain the situation in more detail. The first was by publishing professional

—Schmidt’s Substack is a great resource to learn about the business side of publishing—titled “Publishers Aren’t the Only Ones with a Gambling Problem.”Retailers, both big and small, also consider an author’s sales history important. They know how many copies of a particular author’s previous book their store sold, so they give estimates to their sales reps accordingly. Ask anyone who works in sales for a publisher, and they will tell you how difficult it is to convince a buyer to order a significant quantity of a book if the author’s previous title didn’t sell well. This makes it more difficult for publishers to grow authors beyond two books—or even beyond their debut. While I disagree with the decision to disregard an author who has potential but hasn’t hit their stride, I also understand that publishing is a business with tight margins.

Schmidt explains it in more detail in the piece with examples of how different accounts operate. E.g., Costco only stocks bestsellers and only in the holiday season. Schmidt also makes the point that this kind of situation is common in most industries. Big publishing is a business. Bookstores are a business. Target and Amazon are businesses. Until the revolution comes, well, sales are going to determine how publishing works. Schmidt also makes a point that is hard to disagree with even if few authors, myself included, want to hear it:

We can argue that publishers should dedicate more resources to books with potential. Sometimes, they do. The reality of publishing—unlikely to change anytime soon—is that there are too many books. There aren’t enough publicity and marketing channels for the number of books published each year. There isn’t enough retail space for chains and indie stores to take a risk on a debut or second book by an author with weak sales. I don’t like how the industry handles this, but as you know, I am nothing if not blunt. Authors need to understand how this system works beyond articles that only blame publishers.

I also loved this article from bookseller

titled “Who decides what goes on bookstore shelves?” Fisher writes from the perspective of an indie bookstore buyer and explains what decisions go into deciding what books to stock, and also a glimpse at the kind of numbers involved:Just to give you an idea of the scale of the task of buying: I have about 40 different catalogs on my Edelweiss worklist right now as I start next season’s buy (books coming out in the Winter/Spring of 2026). There are over 14K individual titles in these catalogs combined. I’ll see similar numbers when I buy for the summer, and a bit more when I buy for fall, meaning I see between 40 and 50K individual book titles every year. New books, not backlist.

I often think almost everything about publishing—submitting to lit mags, querying agents, what books are sold, etc.—comes down to the numbers. When there are these vast numbers involved, everyone has to figure some way to winnow them down. Even if a bookstore wasn’t a business that had to pay employees and pay rent, there is simply no way to meritocratically judge 50,000 books a year. How many books does a voracious reader complete in a year? 100? No one can read and judge all these books on their artistic merits. It isn’t remotely possible. So, factors like author platform, comp titles, sales track, and marketing plan are going to determine things.

Another factor that carries significant weight in my decision making process is the sales rep’s “markup.” A markup contains publisher information that the sales rep shares only with buyers. Some of that information is private or temporarily confidential, such as print runs, whether or not the book has been picked by a major book club, and in some cases, what the book even is.

Also, of course, the personal tastes of people in various points in the chain: “I’m almost always gonna buy a book with a rabbit on the cover, and I absolutely could not begin to guess what that’s about.”

Fisher’s article is long and interesting, and also a key perspective—the bookseller’s—that I feel is often left out of publishing discourse. If you are curious about how books are bought and sold, I recommend reading Isen’s, Schmidt’s, and Fisher’s pieces together. Fisher has also agreed to chat with me for a future Counter Craft post, so if you have any questions you’d love to hear an indie bookstore buyer answer, please send them my way.

My new novel Metallic Realms is out in stores! Reviews have called the book “brilliant” (Esquire), “riveting” (Publishers Weekly), “hilariously clever” (Elle), “a total blast” (Chicago Tribune), “unrelentingly smart and inventive” (Locus), and “just plain wonderful” (Booklist). My previous books are the science fiction noir novel The Body Scout and the genre-bending story collection Upright Beasts. If you enjoy this newsletter, perhaps you’ll enjoy one or more of those books too.

The Walrus article by Tajja Isen was fantastic. Thank you for that. I want to state the probably-obvious but socially-unacceptable reason why "track" matters so much: Very few of the people who determine a book's fate actually read them. The agent might. The acquiring editor, in theory, always does. The sales team? The marketing team? The guy who sits in every meeting and bitches about word count, forcing epic fantasy authors to rein it in, because he's been out of ideas for twenty years? Those people just look at the numbers; they don't read the text. Commercial metrics matter because (a) they're immediately evident, and (b) they provide an easy excuse *not* to read. "Bad track, pass. What's next?"

This goes beyond trade publishing, of course. Professors get hired or fired ("denied tenure") based on the h-index, which is the count of published papers, penalized if they aren't cited enough (i.e., to have an h-index of 20, you need 20 papers that have been cited at least 20 times.) This is not hard to game and, unsurprisingly, people do if they want to be employable at the highest levels. It's all metrics because hardly anyone reads in academia either—professors would love to do so, but they don't have time for it, because they're full-time grant-chasers now. Grad students do most of the actual research. But then they leave; there's no continuity.

Publishing gives power to talkers—not readers. And the public reacts to publishing's attitude toward its own product by reading less and less every year. If the decision makers don't read, they set the example for everyone else. It's a game-theoretic sink, like the prisoner's dilemma. Every publishing house is making decisions it believes are short-term optimal, while the long-term effect is that publishing (and literature, since most people only find or read traditionally published books) loses its credibility slowly, one celebrity memoir at a time.

All of this said, the biggest enemy of literature isn't trade publishing at this point. TP sucks right now and it will probably never get better, but the real problem is enshittification, which is damaging self-publishing as well as trade. If we find a way to solve enshittification, then online discovery may work again, and we won't need traditional publishing; given the way the industry is evolving, we should plan not to need it. Maxwell Perkins has been dead for a long time, and the golden age of traditional publishing is almost certainly not coming back.

Thank you so much for this article, and for your whole newsletter. It never fails to provide intelligent, concise, and valuable perspectives on the art, craft, and business of writing. Even having been published multiple times I learn something new every time I read your newsletter.