Three Thoughts on the NYT Top 100: Missing Millennials, Fading Autofiction, the Genre-Bending Era

Looking at some trends in the alleged top 100 books of the 21st century

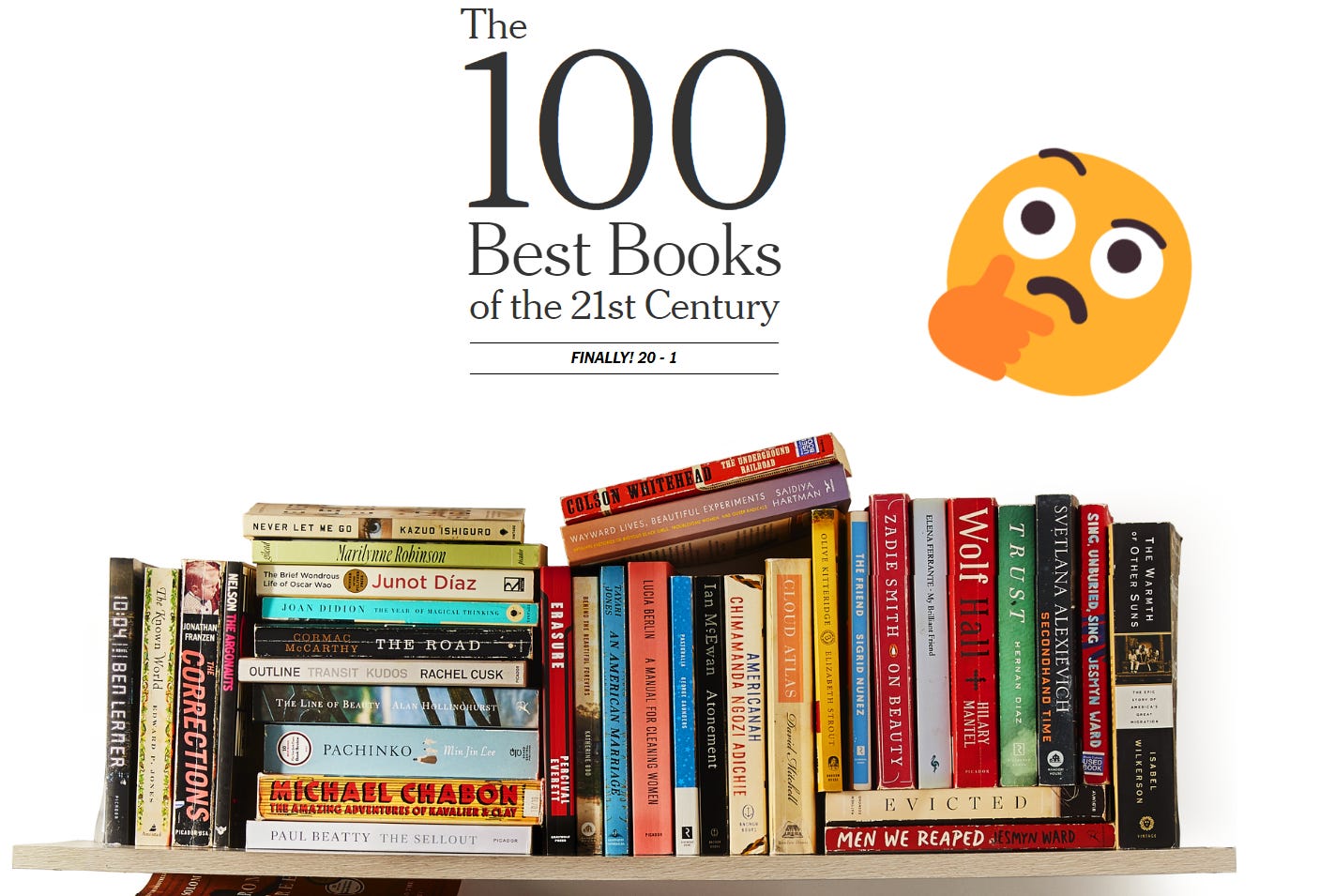

If you pay attention to the literary discourse, you’ve likely been following the New York Times “The 100 Best Books of the 21st Century” list. Like all such lists, it is alternatively interesting, baffling, and predictable. Mostly, it is fodder for conversation. That’s good. Lists may be silly, but they do get people talking about literature and—one hopes—seeking out some new books to read. This one certainly got people talking and was smartly unveiled over a week.

Given the NYT’s methodology—a large survey of authors, critics, celebrities, and pundits—the skews of the results were expected. The top 100 are heavily weighted toward bestselling award-contenders, the kind of books people are likely to have read yet also feel “weighty” enough. It is predictably mostly American and was almost entirely fiction or narrative non-fiction. Poetry is absent, save Citizen. There are two graphic novels and only a couple books that one would find shelved in science fiction, fantasy, or other genre shelves.

I was happy to see some favorite satires—Beatty’s The Sellout (17th) and Everett’s Erasure (20th)—and especially pleased to see the appearance of excellent but unexpected translated novels like Han Kang’s The Vegetarian (49th) and Benjamín Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand the World (83rd). I could argue about many picks and also quibble about methodology, of course. But stepping back and taking a big picture look at the list here are three things I noticed.

Where Are All the Young Writers?

The biases toward American novels (and political and historical nonfiction) and against translated literature, poetry, story collections, graphic novels, and essay collections is notable but also expected. Americans simply don’t read much poetry or translated literature. Similarly, the bias toward big press books instead of indie press books. One thing I spent yesterday discussing with another writer that was surprising—at least to me—is the lack of younger writers. The list is heavily weighted toward writers over 65. There is not a single author under 40. Unless I missed someone, there are only two millennials on the entire list: Fernanda Melchor and Torrey Peters. If you move the cutoff to 1980 births, Justin Torres would also count. Still, only 2-3 titles out of 100 for the generation most of this century? There are no zoomers and even Gen X is underrepresented. This is a list of boomer authors, largely. (Generations are fake of course, but an easy shorthand.)

Probably many will say this is simply because millennials and zoomers have failed to write any worthy books. Yet I doubt anyone who thinks that doesn’t also think the top 100 list is filled with some bad books. You’re telling me that [redacted] and [redacted] are more deserving of a spot than award-winning writers like, for example, Valeria Luiselli, Namwali Serpell, Brandon Taylor, or Hanif Abdurraqib? What does it mean to have a list of 21st century books without any bestselling phenoms like Sally Rooney or Ottessa Moshfegh? Etc.

In one way, I should have expected this since many voters were older and even younger voters were going to use this as a sort of lifetime achievement award. There are lesser works by genius authors who you can tell voters simply felt the need to include. Probably the bigger factor is that younger writers influence can’t be gauged yet. We know Morrison, Roth, McCarthy, Ernaux, and Bolaño have earned their place in literary history and influenced the field. We can’t really say that about younger authors. Their influence hasn’t stuck yet.

Another thought is this may speak to the oft-discussed difficulty in launching big debuts in our modern, social media-fragmented age. The debuts on this list seem to mostly be writers like Zadie Smith, whose White Teeth came out in 2000. That was a very different publishing and media environment. Can publishing still “make” young writers today?

Still, it seems obvious to me that 25 or 50 years from now when someone looks back on this list the lack of younger authors will be an obvious error. Even if the specific authors we’ll all agree (then) were overlooked are hard to know (now).

Autofiction Fictions

Another thing I raised an eyebrow at was the description of the number one ranked novel, Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend, as “one of the premier examples of so-called autofiction, a category that has dominated the literature of the 21st century.”

Like most who’ve read them, I love Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels. Yet I’ve always been baffled by their inclusion in the admittedly nebulous category of “autofiction.” First, they are not seemingly autobiographical beyond the normal way that all books in all genres are inspired in some ways by the experience of their authors. (Even Tolkien brought his life experiences to Middle-Earth. That’s how fiction works.) I appreciate Ferrante’s stance of anonymity, though will say the most likely candidates don’t share the narrator’s life story and Ferrante has said the books are not notably autobiographical: “If, however, you are asking if I’m telling my personal story, none of it.”

So, they aren’t autobiographical. And they share little of the tics, tropes, forms, or even vibe of the classic “autofiction” novels like the Outline, 10:04, My Struggle, How Should A Person Be?, Dept of Speculation, etc. They are not characterized by eschewing traditional plot, character arcs, and scene—quite the opposite, they’re almost 19th-century (this is a compliment) in that regard—nor do they share such works’ penchant for fragments, digressions, or metafictional commentary. As far as I can tell, the novels got this label because they were published when Knasugaard’s My Struggle novels were buzzy.

Anyway, what is more interesting perhaps is despite the NYT saying autofiction has “dominated” literature over the last 25 years—a not uncommon claim in the lit world—the list itself seems to rebuke the claim. The genre is represented by only two books: 10:04 and Outline. Some might argue that two nonfiction works, The Years and The Argonauts, have some of the form and feel of autofiction. Still, if you have to stretch… And either way, the list has no titles from Knausgaard, Heti, Offill, Lin, and so on.

In this regard, the NYT list actually mirrors the literary world. Autofiction has been a much discussed concept among critics. But it has always been more popular for think pieces than for readers or even awards committees. Few autofiction books sold terribly well—especially when we don’t include Ferrante—and the list of Pulitzer, National Book Award, and Booker finalists are surprisingly free of the famous autofiction titles. (One exception is Ben Lerner’s third, and least, novel being a Pulitzer finalist.)

If there was anywhere autofiction should shine, it is exactly a list of critics’ favorite books. What does it mean that so few made the cut?

None of this is to say autofiction isn’t valuable or interesting, or that it hasn’t produced some excellent works. I love Cusk’s Outline trilogy, Lerner’s first book, and others. But when I look back at the last twenty-five years of fiction, I see another trend dominating.

The Genre-Bending Era

I think one can make an easy argument that the biggest trend in the literary fiction world has been, in fact, genre fiction. Or rather “genre-bending” work that bridges literary fiction style and themes with genre fiction tropes and concepts. Like autofiction, this is a fraught term. Both are labels people can claim are hardly new at all. There have always been books that blurred literary style and genre tropes, and however you define autofiction there are precedents stretching back centuries. But labels can be useful for thinking about larger trends in culture. And anyway, what’s the point of a literary newsletter but to dissect such hobbyhorses?

So, why is “genre-bending fiction”—or, if you prefer, “speculative fiction that’s finally celebrated by the mainstream”—the dominant fiction trend of the last 25 years? Well let’s turn to the NYT list itself. You have acclaimed and award winning science fiction (Never Let Me Go, Station Eleven, The Road), fantasy/magical realism (The Underground Railroad, Exit West, The Fifth Season), and general genre-bending works (Cloud Atlas, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, and all three titles by George Saunders). There are some others one could argue for too.

We would not have seen this in a list made 25 years ago. In the 80s and 90s, realism still dominated and the Pulitzers, National Book Awards, MacArthurs, and the like gave little consideration was given to works one could describe as science fiction, fantasy, or horror. The last twenty-five years have radically changed in that regard. The titles and authors above were winners of Pulitzers, NBAs, MacArthurs, and even Nobel Prizes. Some were Oprah picks and many were bestsellers.

Outside of the NYT top 100, we could list many other titles. Along with Saunders’s work, the most influential short story collection for younger writers is—in my experience as an MFA professor at least—Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties. Add in acclaimed and influential works by Kelly Link, Jonathan Lethem, Victor LaValle, Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, Brian Evenson, Charles Yu, etc., as well as other titles from the authors above such as Whitehead’s Zone One and Ishiguro’s The Buried Giant…. the list could go on for some time. Genre-bending books have been big sellers, award winners, and (again at least in my experience as a writing professor who discusses such thins with colleagues) a huge influence on younger writers. This is not limited to literature. The bridging of “highbrow” or “prestige” work with genre narratives has been a dominant trend across mediums. Think of the acclaim for shows like Black Mirror, Severance, Game of Thrones, Handmaid’s Tale, Westworld, Twin Peaks: The Return, and so on. But the trend in literature has been just as strong. As someone who loves and writes such work, it has been a welcome shift.

Okay there are three thoughts on the list. And for what it is worth, here are 10 books I personally would include on my own top 100 list that did not make the NYT list: By Night in Chile, Signs Preceding the End of the World, Fifteen Dogs, The Story of My Teeth, Windeye, Piranesi, The Memory Police, The Visiting Privilege, Debt: The First 5,000 Years, Fever Dream.

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.”

Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

Never mind piranesi -- Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell was not in the list! (I certainly prefer it to the broken earth trilogy.)

I'm going to say that the most interesting thing someone could say is not what is missing from the list, but what*doesn't* belong on it. I think it's far more revealing of aesthetic distinctions.

I was honestly disappointed by how completely provincial the list was. We live in a golden age of literary translation and have access to more international literature in English than we've ever had before...87% of the list is books originally written in English. Like I get it's the New York times and it's an American publication...but how predictably pathetic of the New York times to include three George saunders books at the expense of any single book from say Spain, or Austria, or Russia or Brazil, etc. It's a small minded idea of what constitutes great literature in the 21st century