The Classics Are Whatever We Want Them to Be

Classic books are a lot more varied and enjoyable than people think

One depressing thing about literary social media discourse is there seems to be a handful of ridiculous, reductive debates that go viral every day. Genre vs. literary fiction. “Are MFA programs scams?” And, of course, the most popular one: “all the classics are garbage!”

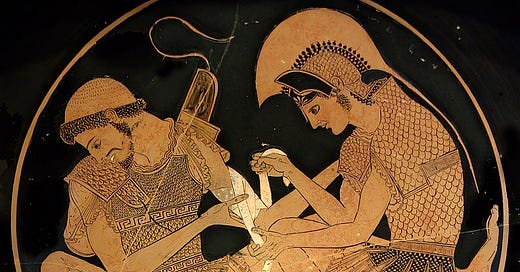

The most recent round of “classics” discourse was kicked off by a self-proclaimed former English professor who said they had *never once* enjoyed a classic book. Nor had their students. (As Nick Mamatas pointed out, the thread got even more ridiculous when it proclaimed the classics never had non-Christian or queer perspectives while mentioning only one book by name: The Iliad, a decided not Christian work where a central part of the story is Achilles going ape shit because his gay lover Patroclus has been killed in battle.) The upshot was that we should chuck out all the classics and replace them with contemporary YA books.

There’s a lot going on here, and I have no interest in shaming this Tweeter by name. But the sentiment is pervasive and one that I’ve found baffling. A “classic” is not an entry on some fixed list of books in Harold Bloom’s old office. Most of the time it is just a term for older—let’s say >25 years—books that we still read. As such, claiming that the classics are just the work of “straight cis Western white men” doesn’t strike me as a progressive stance. It’s a complete erasure of centuries of writing by women, queer writers, people of color, and authors from around the world.

Let’s agree up front that everyone thinks students should be taught a diverse selection of literature. Okay, a lot of Republican legislators don’t, but just about everyone who is involved in academia, publishing, and online literary discourse does. It’s certainly true that for a long time high school and college syllabi have been mirrored society’s biases, and it also is true that—thankfully!—this has changed quite a lot in recent decades. We should continue to fight for broader and more inclusive syllabi. But the question of the diversity is a completely separate question from contemporary books. It is quite easy to construct a syllabus of classics that includes zero straight white men. Countless such courses are taught literally every semester in colleges around the country. As they should be!

The classics are whatever we want them to be. We have the whole of literature—that’s survived at least—from across time and around the world at our fingertips. The classics exist in every country. In every genre. In every decade. And by authors of every creed, background, and body. It’s up to us as teachers, or individual readers, to pick and choose which we want to read.

So if we’re in agreement that the classics include not only Herman Melville and William Shakespeare but also Toni Morrison, Sappho, Murasaki Shikibu, Gabriel García Márquez, James Baldwin, Tayeb Salih, Simone de Beauvoir, Zora Neale Hurston, Jane Austen, Arundhati Roy, Chinua Achebe, and [insert endless list of authors from around the world and throughout history] we can move on to other questions.

Why read classic books? One reason is that classics are not dead texts isolated in the past, but works that still resonate in our culture today. “A classic is a book that has never finished saying what it has to say,” Italo Calvino famously said. This is true in the abstract sense that our culture did not emerge out of the blue. We are shaped by the past, so it is good for us to understand it. But it’s also true in the very concrete sense that classics are an active presence in contemporary culture. Take the tweeter’s example of The Iliad. One of the biggest successes of BookTok—that is mostly young people on TikTok who talk about literature and drive a lot of book sales—is Madeline Miller’s Song of Achilles, a 2011 retelling of The Iliad. Perhaps the most acclaimed video game of last year was Hades, a Greek myth-inspired game that features, among many other Greek literature characters, Achilles and Patroclus.

More generally, why do we read literature at all? Surely a fundamental reason is to enter the consciousness of people who are not like us or who are in radically different situations than us. You can call this promoting empathy—although I’m skeptical of that—or literature as a way of teaching us history and other subjects. Whatever you call it, literature is an art that expands our consciousness by connecting us to other consciousnesses.

How could you look at this great power and say it must be shrunk? To look at all the literature from word history and say, nope, a modern American student can only connect with work from other American authors written in the last few years. The rest of the world and the rest of history is useless to them. I find this attitude condescending towards teenagers and a rather nihilistic statement about humanity. If we are so incapable of connection, so narrow in our vision, what hope do we have at all?

Luckily, I think this idea is quite false.

Teens are far more capable and open than adults give them credit for. So are older students and students in general. I’ve taught a wide range of students from teens to older adults, classes of mostly white students and mostly POC students, classes of working class (and first gen) students and classes of middle/upper class students, and all of them have been quite capable of being engaged and connected to older authors from Plato to James Baldwin.

Yes, a lot of teens hate their English class homework. Guess what? They also hate their calculus homework and their biology homework and their Spanish or French homework. A lot of teens hate school! It’s pretty understandable for a lot of reasons, including the aforementioned condescending attitudes of some teachers. But of course many students find English is their favorite subject. Certainly I remember far more about the books I read in high school, whether I loved them or hated them, than I do whatever lessons I had about Punnett squares and co-sine functions.

There’s of course nothing wrong with reading YA fiction—there’s plenty of great YA literature, as with any genre—and there’s nothing wrong with reading contemporary books. We should always read widely and omnivorously. But that includes the classics, which, again, include most of the literature humans have produced.

Like many teenagers, I was awkward and lonely. I felt like an outsider. I yearned for a different life. Also like many teens—especially those who grew up to be writers—I found my way into the world through art, especially literature. And the literature that connected with me, that either made me feel seen or made me see in new ways, had no time or geographic restrictions. I discovered my love of literature through writers like Jorge Luis Borges, Ursula K. Le Guin, Haruki Murakami, and Ralph Ellison (of all the novels I was assigned in high school English class, none opened my eyes like Invisible Man.) I’m not saying those are the most diverse writers by any means—none are terribly old, for one thing, although I also loved studying Shakespeare’s tragedies and the Greek plays in high school—but I got more from those older and/or foreign authors than I did from any of the contemporary American books marketed to my age bracket. I don’t think I’m unique in this regard.

Did I hate a lot of the classics assigned? Of course. Did other students love those ones and hate the ones I loved? Yep! Do people alternatively love and hate every single contemporary book? Absolutely. You’re never going to find a list of books that everyone loves.

But to end here I want to cycle back to the idea of never enjoying the classics and say something that maybe isn’t said enough: a lot of the classics are just great! Like, they are way more enjoyable and funny and interesting than their dour reputations. One Hundred Years of Solitude is a wonder! Pride and Prejudice is hilarious! Sula is unforgettable! Moby-Dick is astounding! These books haven’t lasted because of some secret cabal of evil English professors are hell bent on destroying literature. They’ve lasted because they’re pretty darn good. Forget importance and connecting to other consciousnesses and what not. They are just really fun, enjoyable reads.

Oh yeah, I hear The Iliad is pretty good too.

As always, If you like this newsletter, please consider subscribing or checking out my recently released science fiction novel The Body Scout, which The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent” and Boing Boing declared “a modern cyberpunk masterpiece.”

I love how the original tweet just completely ignores the Brontë sisters and Mary Shelley. The OG weird girls. Foremothers to every Goth intellectual with a shitty poetry side blog. I’d argue that Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is a more commonly referenced and understood work than 99% of Shakespeare’s plays, but that could be sample bias, as I mostly read fantasy/horror anyhow.

Their argument (if you can call it that) also sidesteps how, yes, sometimes teens *are* deeply annoyed by classics because of the class/race/gender dynamics they contain. But they should still be given the tools to examine why that is, and determine for THEMSELVES what themes and character dynamics are irksome, which are an essential part of the genre and which are an essential part of the author’s worldview.

I read Emma as a poor teen and couldn’t stand it; Emma creating non-issues for herself instead of minding her own business annoyed me on a spiritual level, and I was just bored overall. Disliked Clueless for similar reasons (now *that* is an opinion that didn’t go over well). Am I now biased against Jane Austen and the novel of manners as a concept? Yes! Did I learn something important about my own taste in protagonists? Also yes!

Even disappointing reading experiences can be fruitful. Disappointment is the great spice of life and excellent fuel for idea generation.

I also think that part of students not enjoying certain Classics is them being unaccustomed to reading plays and poetry. Those are separate learning curves from learning to read a novel. It’s still hard for me to read Shakespeare simply because of the formatting.

Okay, sorry but I decided to delete all the comments debating whether European art is superior to art from other cultures as that's absolutely the opposite of the points I was trying to make and this is my personal news letter not an open forum.

To be clear to Kit and Ani, I agree with what you said about the argument being racist. But I'd rather remove the whole thread from this wall (including my own comments). Just rather not have that archived here.