Ramen Westerns and Thematic Cores

A movie rec, and thoughts on improvisational narratives and unifying stories by theme

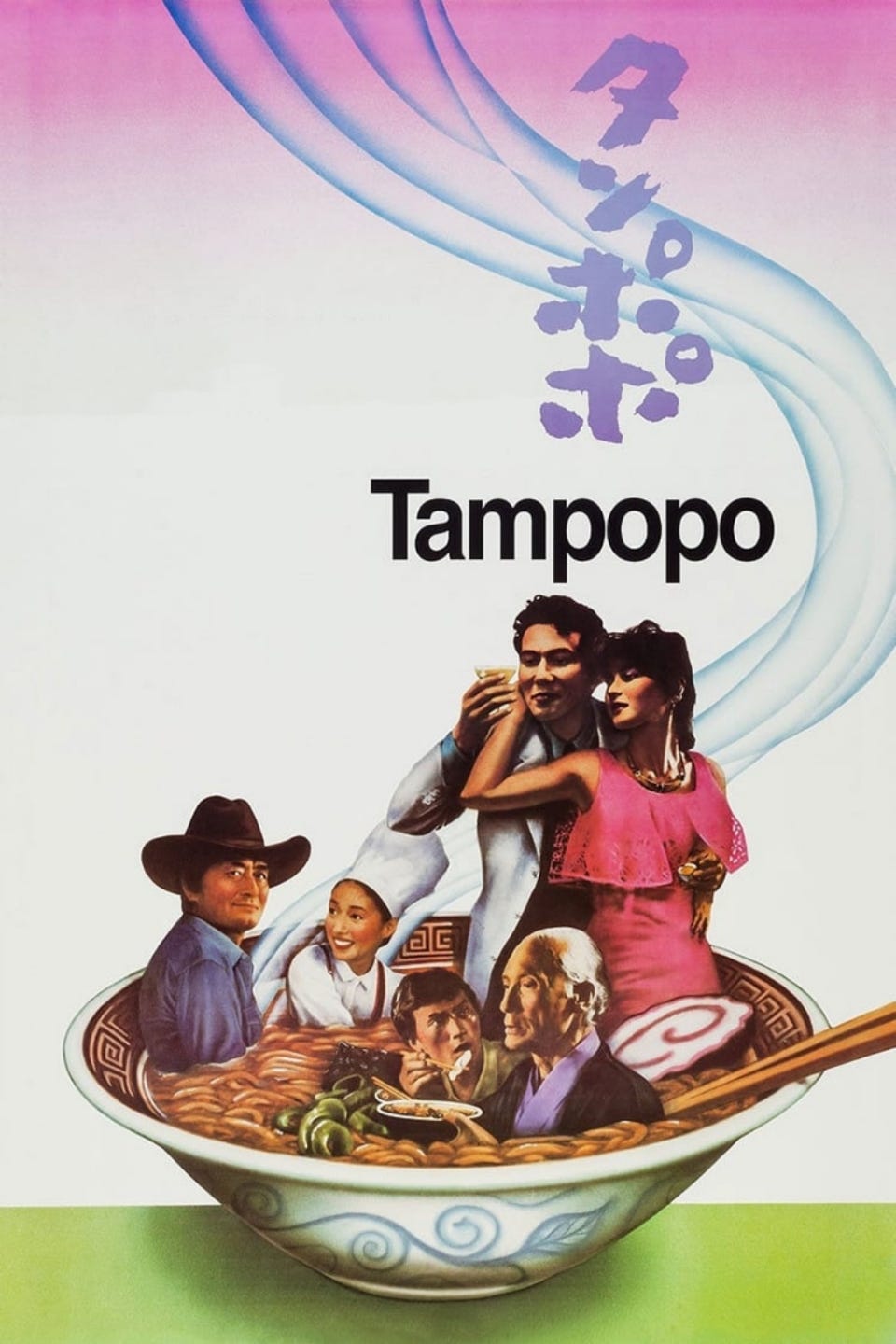

A couple weeks ago, I watched a movie I haven’t stopped thinking about: Tampopo, a 1985 Japanese comedy written and directed by Juzo Itami. The loose plot involves a trucker who helps a woman turn her crappy ramen spot into a first-class restaurant. Itami called it his “Ramen Western,” riffing on the Spaghetti Western. It’s filled with pastiches and parodies of American action films, and does feel at times like Sergio Leone processed through a Monty Python filter. It’s also quite lovely and moving. If you’re a fan of anarchic, surreal, and beautifully filmed comedies then perhaps you too will enjoy it.

So, this post is in part a recommendation. The film is currently streaming on Max. (I’m not sure where else to put this fact, but I later learned the director was likely killed by the Yakuza.)

I’ve also been trying to think about why the movie both snatched my interest and has lurked in my mind sense. I think the reason is not so much the main plotline—as fun and enjoyable as it is—but because the film is filled with strange little digressions. There’s a delightful series of vignettes featuring a gangster character and his lover (who never interact with the main plot) and a host of other one-off scenes and characters such as a spaghetti etiquette class devolving into ravenous slurps:

These scenes add a madcap and even improvisational quality to the film. One gets the sense the director was indulging whatever delightful and bizarre ideas occurred to him in the moment. I love this quality in novels too. Where I can see the writer think to hell with rigidly paced plot beats and traditional character arcs, I’m just going to put in whatever interesting asides or ideas I think of! This improvisational feeling is a lie. Making a movie—like writing a novel—is not a jam band session or an improv show. Even a rushed film takes quite a long time to write, film, and edit. Even quickly written novels have months of revision. But when done well, such freeform works can feel more writhingly alive than those with polished plotlines.

A novel I recently reread with a similar ravenous and improvisational quality is The Story of My Teeth by Valeria Luiselli (a book I think was missing from the recent NYT top 100 list). That novel has a loose plot and shifts styles each chapter. E.g., one chapter involves the auctioneer narrator inventing little stories to sell teeth he claims are taken from historical and contemporary figures. In Luiselli’s case, there was a sort of literal improvisational element to the work. The book was written chapter by chapter to be read to workers at the Jumex factory. The workers provided feedback, which informed later chapters. The result is wild and unique.

I also think, as I often do, of Italo Calvino. Invisible Cities has some of this quality, although it comes about it from the opposite direction.

[Invisible Cities] was born a little at a time, with considerable intervals between one piece and the next, rather as if I were writing poems, one by one, following up varying inspirations. Indeed, in my writing I tend to work in series: I keep a whole range of files in which I put the pages I happen to write (following the ideas which come into my head), or mere notes for things I would like to write some day. In one file I put the odd individuals I bump into, in another the heroes of myth; I have a file for the trades I would like to have followed instead of being a writer, and another for the books I would like to have written had they not already been written by somebody else; in one file I collect pages on the towns and landscapes of my own life, and in another imaginary cities, outside of space and time. When one of these files begins to fill up, I start to think of the book that I can work it into.

Instead of being written quickly, Invisible Cities was collaged together from work written over a long period of time. Yet the result is a similar joyous, anything-goes feeling.

How does one hold such works together? How can “anything goes” become a singular thing going in certain direction? I think the answer is simply theme. A strong thematic organizing principle can take the place of traditional plot and character in cohering a story. In the case of Invisible Cities, that thematic core is cities, travel, and attendant ideas. In The Story of My Teeth, it is stories and the blurring of truth and lies. In Tampopo, the core is food and the way sustenance is entwined in our lives from birth to death. Each of these works—and surely many others that could be named—use their theme as a lens on all of human life. But the thematic core works to unify the disparate parts without traditional plot and character arcs. Or with those arcs more muted and in the background.

At least that’s a theory. And if you are looking for an interesting and funny and moving film to watch this weekend, try Tampopo.

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.”

Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

I was recently recommended Manhattan Transfer by John Dos Passos and it has a similar feel, loaded with seemingly unrelated streams of consciousness and non sequiturs that are quite expertly tied together.

Another great one, Lincoln. Thank you! I’ve been a jazz musician for 20 years now and for the last 15 of those have been a heavy practitioner of free jazz and free improvisation. For the past three years, I’ve been writing, nothing much good yet, but I’ve really loved the journey so far. As a result of my background, I think often think about the improvisational quality you reference. I love when I feel it in works. And I miss it in my own work. It feels daunting to try and break free of the self-conscious voice that starts screaming about self-indulgence and plot beats and unnecessary sentences. I feel I end up with a sterility that I don’t enjoy in my own work as a result but that feels safer and that in and of itself, as someone just trying to make some art, is just… not fun.

One thing I’ve been thinking about in terms of balancing this in an art form that doesn’t share the same fleeting temporality as the freely improvised music performance is the role of listening. In free Improvisation, the best improvisers have the biggest ears, are able to hear what’s happening around them on the bandstand in the most eager and lucid way and know when to build, when to destroy, when to augment, when to disrupt, and when to stay silent (the hardest part for some ((most)) people). The tiny voice in your heard that says, that’d be a bad idea to hit that going right now or what if this ruins the vibe, you don’t have time to hesitate in free improvisation, you can hear hesitation and it’s the worst thing you can become aware of as a listener.

I’ve been really trying to cultivate what the parallel might be in the practice of writing and I’m tempted to say the story itself is the fellow improvisers. The world outside of yourself while you’re tucked away behind a drum-set and being able to open your ears to feel, really feel, when to drop the bomb, when to stay silent, when to steamroll, when to make a joke and in the lovely tradition of Han Bennink stick your teeth out, put the brushes on your head and pretend to be a rabbit (the Dutch are the best). I think about the Bernhard quote about seeing stories and shooting them down all the time and what that makes him as an improviser, what listening meant to him, and how he became so big earred that the cracking of a twig in the forest was enough to get him cocked and aiming. As a reader I begin to hear him listening, and that is so satisfying to me.

I want that quality in my own work, deep listening. I don’t know if I’ll ever find it and I don’t know if I can silence the voice that makes me hesitate. I’m ready to follow any author on any ramble, I’m ready to at least give it a chance before saying “why?” But I feel like I don’t give myself the same grace as a writer. Any thoughts on how to open up and stop worrying and love the bomb? Or is it just a case of knowing rules before you can break them and know that as voice and style and ears develop these things sort themselves out in way or another? Or am I just a self-indulgent jerk who needs to read more Hemingway? Thanks again Lincoln, always love getting Counter Craft on my inbox!!