Processing: How Tracy O'Neill Wrote Woman of Interest

The author on writing both fiction and memoir, being "an enormous nerd," and making sentences that move

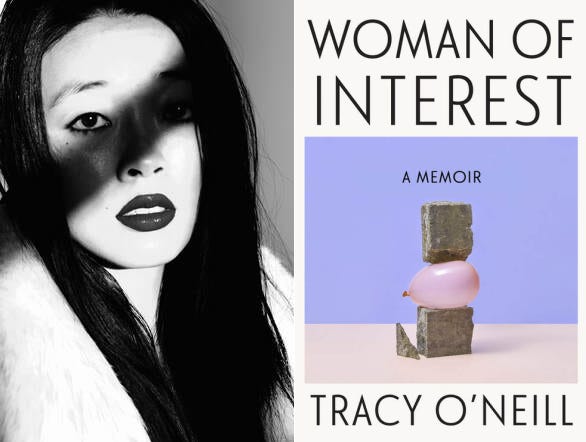

On a semi-regular basis, I interview authors about their writing processes and craft practices. You can find previous entries here. This week, I’m excited to be talking with Tracy O’Neill, whose new memoir Woman of Interest is out today. The book chronicles O’Neill’s decision, during COVID lockdown, to track down her birthmother in South Korea. Structured like a mystery and written in hardboiled inflected prose, Woman of Interest is singular, stylish, and riveting. (O’Neill is also the author of two excellent novels: The Hopeful and Quotients.)

I talked with O’Neill about moving from fiction to memoir, writing one’s life as a mystery, and “the social activity of language.”

When we talk about memoirs, typically the focus is on the story. And the story here is very complex, gripping, and moving. However, I wanted to start by asking you about style. Your prose is very stylish with sentences that buzz and sting. How do you approach writing sentences in general? And how did your approach change—if at all—from writing fiction to writing a memoir?

For me, writing a sentence anticipates the shifting experience of reading-it-through-time. Ideally, a sentence doesn’t just strike a pose. It moves. So, for instance, I’ll try for a sonic push built out of rhythm that, at a point, I’ll knock the block off. But, of course, those rhythms and the sense of advancement or falling back are tied intimately to the mood and meaning. My project isn’t strictly formalist. I’m reaching for meaning and trying to throw meaning, which is to say, I’m invested in the social activity of language.

There are writers whose voices are unmistakably, wonderfully theirs over various projects. The demands of each book result in different voices in my body of work though. This one required more exasperation and abruptness in the voice than Quotients, for instance, because I was rendering a character—myself—who happened to be, to my own chagrin, exasperated and abrupt often enough.

Woman of Interest has a fascinating hardboiled and spy thriller feel to the prose. This is apparent even from the table of contents with chapter titles like “Leave No Witness,” “Hearsay,” and “Red Herring.” It’s a perfect and distinctive choice, I think. I’m curious if you’d always planned to write in this hardboiled-tinged style? Did you (re)read detective novels while writing?

From the beginning, I knew I’d inflect this book with elements of noir. Even as a child, I understood that the mother who didn’t raise me was largely seen to have violated the codes of conventional womanhood. You don’t have affairs. You don’t abandon a child. And, of course, there was the compulsion to investigate and the alienation of the detective that I saw in myself too. So the generic nod felt almost built in to how I understood the story.

I read Missing Person by Patrick Modiano early in the writing, and I re-read “Death and the Compass” by Jorge Luis Borges. In general, I love a narrative propelled by questioning, which is what detectives do.

The memoir is somewhat metafictional about this in the way the narrative references detective and spy novels. You signal this on page one with the line: “Time itself felt ‘dark with something more than night,’ as Ray Chandler might have written.” Other authors, like Roland Barthes, are quoted too. Can you talk about the decision to include these intertextual references?

My sense: I had to. Memoir must provide a view into the narrator’s mind, and as it turns out, I’m an enormous nerd. I’ve spent an ungodly portion of my life reading. Books aren’t exterior to my life. They are also experiences, also living, and I’m prone to relating them to non-textual experiences.

The story of Woman of Interest involves your trying to track down your birth mother in Korea. One thing that struck me is how well-plotted the book is. It feels strange to say that about a memoir, about real life events, but the book is expertly structured and paced. As someone who has never attempted a memoir, I’m curious how you went about structuring the book. Did you have an outline, for example?

I didn’t begin with an outline. I started writing the book with some probably delusional psychological mechanisms at work. It was just me and the illusion of control, the desire for clarity, the comfort of turning to “the work,” the idea that meaning-making could happen on the page though it didn’t feel as though much meaning was being made otherwise.

At some point, when I had written the first third, I created a loose outline. Then I had to abandon some of it, yes, for plotting—but also because my life changed, and I needed a new structure that could hold it. For example, I needed to backtrack and include more instances of tension with one character in particular.

The final chapter was not at all what I originally planned for two reasons: 1) It was going to end on a sort of redemptive and unqualified love letter to language and storytelling that I realized would be full of shit—even if I didn’t want it to be, and 2) I had to admit that the arc I imagined for the character and real person, Tracy O’Neill, wasn’t my actual trajectory; I was still, in various ways, a mess.

Since I call this interview series “processing,” I always like to ask if you have any particular writing process. Do you write by hand then type? Always work at a specific desk? Etc.

I always work at home, at my desk, on the computer, and with a glass of water and a mug of coffee to the right. I drink roughly thirty beverages a day.

Can you talk about the timeline of writing and selling this memoir? Whatever you feel comfortable sharing.

I started the book in 2020, writing about various experiences shortly after they happened. Then I stalled out in the real-life investigation, and I wrote nothing. Then I felt that I should continue writing the book even if I didn’t find my missing woman. There was something inescapable about the compulsion to look for her, whether or not I found her, and inescapable about my sense that I needed to become a writer who could write something more personal and open-handed.

The book sold early in the summer of 2022 off the first third. The next chapter took me all summer. During the fall, I didn’t write anything. I was teaching a lot and very upset with myself for spinning out over the previous two-plus years, so I wasn’t all that game to spend even more time thinking about that in the writing. Then I finished the book late in the spring of 2023.

Woman of Interest is your third book, following two excellent novels, The Hopeful and Quotients. What were you able to carry over from fiction writing and what did you have to learn anew to write a memoir?

When I wrote the first book, I had no idea how to write at length. I remember a professor telling me, after she read the first forty pages, that she had no idea how I’d be able to continue the narrative any further. In those first two books, I was learning how to advance past a situation and think about time unfurling.

In this book, I needed to recognize that some crucial parts of my life story were not the story of the memoir. Originally, there were large sections of book about the woman who once might have become my mother-in-law. I had loved her, so I spent several pages describing her ripping butts and picking raspberries. That sort of thing. But I had to accept that writing about her did not serve the narrative I had set out to tell in Woman of Interest.

Lastly, any advice for any first-time memoirists reading this?

Remember that human life is finite. Take that as you will.

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.”

Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

"There are writers whose voices are unmistakably, wonderfully theirs over various projects. The demands of each book result in different voices in my body of work though."

However, I'll bet the reader will spot similarities. The leopard can't change spots so easily : )

Tracy is quite wise, though some of what she says is a little opaque, or maybe stylized. For example, what does this actually mean? “I’ll try for a sonic push built out of rhythm that, at a point, I’ll knock the block off. But, of course, those rhythms and the sense of advancement or falling back are tied intimately to the mood and meaning.” In any case, great interview overall. Looking forward to more of these!