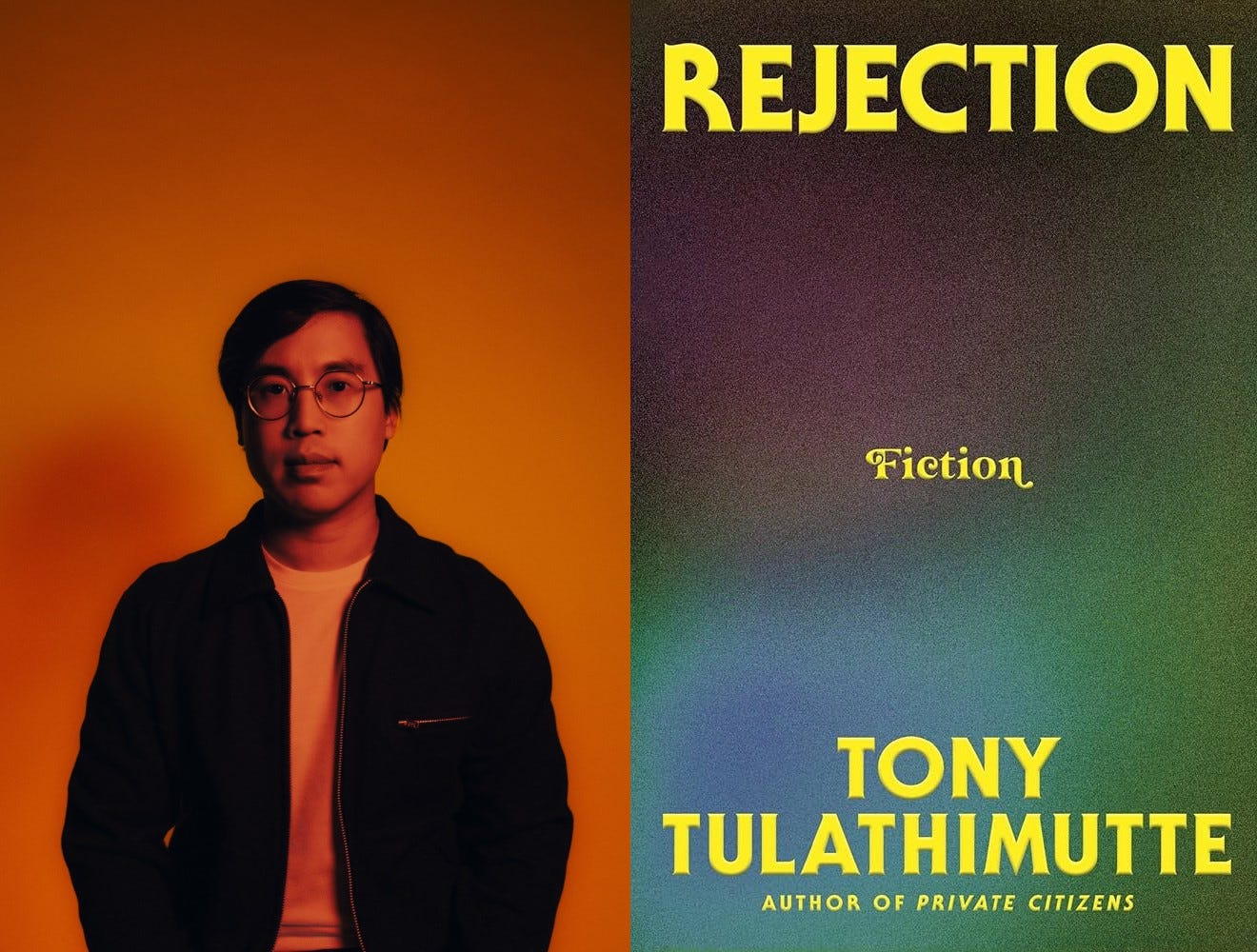

Processing: How Tony Tulathimutte Wrote Rejection

The author on comic disproportion, revision, internet language, and pledging yourself to idiocy in fiction.

On a semi-regular basis, I interview authors about their writing processes and craft practices. You can find previous entries here. This week I’m very excited to be talking with Tony Tulathimutte, whose new book Rejection is one of the most hilarious, outrageous, and brilliant books I’ve read all year. (It was longlisted for the National Book Award just this week.) Rejection is a sort of novel-in-stories examining “rejection” in various forms from the point of view of interconnected characters who are alternatively not self-aware enough and far too self-aware. The stories are ruthless in their satire, stylish in their prose, and fearless in their commitment. I talked with Tulathimutte about revision, comedic disproportion, and pledging yourself to idiocy in fiction.

There’s so much I admired in Rejection from the sharp prose to the deranged (complimentary) humor, but maybe what I loved most was the book’s audacity. I kept thinking Wow, he’s really going there! This is a bit vague, but can you talk about audaciousness in fiction? Is pushing your stories further and further something that happens more in drafting or in revision?

It's always revision. When I’m drafting I have no idea what the story is about or what effect it’s going for. You need to keep a loose grip on your intentions for the story in these early stages, because often what you think you’re going for will diverge from what the story wants to be. “Ahegao” makes a good example; the ending is an obscene 4,000-word description of a custom-order porn video, and in the early drafts I’d just glossed over it in a page of summary. But I kept going back to it to add more, and feeling guilty because I thought it was a digression, it wasn’t moving the plot forward, and it was quite literally masturbatory filth. Eventually I reversed my thinking and restructured the story entirely to support the long version of that ending, because honestly that was the part that interested me most; even if it was silly and excessive, that just meant I had to make the silliness and excess the point. The story’s theme followed suit—it became a story about repression and expression, not coincidentally the issues I was dealing with while writing it. In general you just have to follow along with whatever’s productive.

One of my favorite bits of writing advice I took from you: “Pick your dumbest idea and write it as seriously as possible.” Hopefully I didn’t butcher that. It really is an excellent way to write a story. Was this a principle guiding Rejection?

Most certainly. For “Ahegao” and “Our Dope Future” I pledged myself to idiocy in different ways. The trick works because it takes the pressure off, and you can just commit yourself to the process. If you write something stupid and bad, then it’s not a letdown and any draft can still be salvaged, but if you manage to write something stupid and surprisingly good, then voila. Of course “stupid” is a judgment you make on an idea that supposedly “shouldn’t work,” but a lot of writing is about making it work anyway by finding the right voice or form. You need to believe that in principle anything can be pulled off and it’s just a matter of finding out how. After that it’s a matter of throttling your ego and ignoring those inhibitions that come up like This isn’t my kind of writing, what will people think about this, this isn’t what I intended, and so on. You have to just try it first and then decide whether it’s worth pursuing, or whether you have to just towel off and move to the next project.

These stories are character driven, but more specifically driven by the consciousnesses of the characters. It’s a deeply interior book in some ways. You dive down to the murky floor of their minds, stirring up their secret desires, fears, and horrors. The characters are all very distinct though, with different identities, personalities, and politics. How did you get into the mindset of a given character when writing?

In comedy it’s good to lean into disproportion. All the protagonists in Rejection generally think in ways that feel natural to me, but then I dial up a preoccupation or sensitivity that sort of overpowers their other tendencies. With “The Feminist,” his otherwise relatable anxieties about signaling his feminism are so intense that they make him oblivious to the effect he has on other people. In “Pics” Alison’s desire to project an interesting and powerful image, and her susceptibility to other people’s images, consistently outstrips her ability to do so. Getting the balance right is important, because if you make a character too single-minded then you just get a flat caricature or allegorical finger puppet, and if you go too far in the other then it can feel weak or smudgy, you can end up with this lockjawed ambivalence that tries to pass itself off as subtlety or nuance.

From there the character and the situation work to define each other—a character acts toward their intentions, and the consequences feed back into their personality. Also, I’ve said this elsewhere, but in general it’s good for comic purposes to have the characters just be 30% more selfish than a reasonable person would be, and to want something sort of ignoble or dumb, and fail to get it.

I’ve read a lot of funny books. But Rejection stands out as one of the few books I’ve read that successfully translates cringe humor to the page. It reaches Larry David levels. What is your approach to comic fiction? Is your writing influenced by any comedians or works of comedy?

I watch a lot of standup, but it’s almost impossible to translate that kind of humor to prose because the timing works way differently, so it’s mostly other writers I’m pulling from. The Brits basically invented cringe, and I think a lot about writers who toe the line between manners and transgression, like Martin Amis and Alasdair Gray. Alissa Nutting is great at hitting that register of comedy that’s almost horror, and I like to say the two genres work the same in how they use tension and payoff. I took a lot from the tone / content dissonance in Dennis Cooper’s The Sluts, and Helen DeWitt’s book-length commitment to the bit in Lightning Rods. But I’m probably most directly influenced by my writing group, both in their writing and feedback. Jenny Zhang and Alice Sola Kim figured out interesting ways to do comedy way before I did.

A lot of contemporary fiction struggles with the internet, despite how much it shapes our lives. I loved how Rejection works in social media posts and other online material. I think this is in part because you take the language of the internet seriously as language. As a building block of art. One way you do that is with form. “Our Dope Future” is written as an AITA post, “Main Character” is in the form of an internet guide, “Pics” includes long group-text exchanges, etc. What’s your approach to incorporating the internet in fiction?

I think writers bungle internet writing when they overrely on superficial signifiers—hashtags, acronyms, memes, discourse references—without really picking up on the cadences specific to the platform they’re writing about, or what motivates people to use it, or the different variations and subcultures endemic to it. It’s not just a problem with the internet, there’s a similar issue with fictional rock / rap lyrics and child-speak too. Sometimes you can also feel an undercurrent of contempt for the internet’s ostensible debasement of language, and attempting to make that point too strongly will only blind you to its pleasures; ironically it’s just the writer’s work that suffers as a result. (There’s no “debasing” language to begin with, there’s only missing your target.) For some examples of writing that I think does it well, there’s the momfluencer Instagram posts in Alexandra Tanner’s Worry, the Gchat scene in Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station, and the Slack chat in Calvin Kasulke’s Several People Are Typing.

Speaking of form, there are two other formally playful stories at the end. I won’t spoil them. But is form a sort of Oulipian constraint that guides a story from the beginning? Or does the form reveal itself for you during drafting and revision?

Both really. I don’t usually know what the form will be at the outset, so I need to rewrite until I figure it out, but once I do, it becomes a scaffold and source for new material.

Rejection has a clear theme uniting the collection. The titular rejection. Did the theme predate the stories? Or had you written some of the individual stories first before realizing they could anchor a collection in this way?

Yeah, the theme and title both came first. I just knew I had a lot to say about it. And no shortage of material.

I’m calling these stories, but the stories are interconnected, and the work is titled not “stories,” “a novel,” or even “a novel-in-stories” but simply “fiction.” Why did you decide on that label for the book?

I didn’t, my publisher did. I have always considered it a novel, but my definition of a novel probably isn’t shared by everyone. Anyone who randomly picked the book up would probably call it a linked story collection, even though they’re arguably not all stories. So it was sort of a hedge to call it “Fiction.” (Another funnier reason is that the title Rejection keeps getting the book lumped in with nonfiction and self-help in online databases, which is why on a lot of sales pages the title comes up as Rejection: Fiction.)

I understand Rejection went through a few different structures, including having non-fiction portions at one point. Can you talk about the process of writing and revising the book? Whatever you’d like to share.

I’ll try to keep it short. Starting back in 2011, the idea was to cover the topic in as many ways as possible—different genres and forms within fiction and nonfiction, like vignettes, lit crit, logical propositions, a glossary, and so on. After focusing on Private Citizens for a few years I came back to it around 2018 and reconceived it as stories and a long essay, but the fiction ended up outweighing the nonfiction by about 3:1, and after selling the book in 2022 I ultimately cut the essay, though it’s been adapted for publication elsewhere (as “The Rejection Plot” in The Paris Review and “Creeps” in Mixed Feelings).

Like I’ve said, the form of the individual stories took a lot of work; the first three stories share a similar mode, but the others had to be rewritten a lot from scratch—“Main Character” in particular took four tries.

Any advice for a reader going through rejection in life and/or literature?

In general, don’t dispute or haggle. Also, when you’re not ready for, correct about, or deserving of the thing you want, acceptance is worse than rejection.

If you enjoy this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.” Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

My favorite Tony-themed interview this go-round (and way more interesting than the NYT piece). I was in Tony’s Stanford-and-after-Stanford writing group before we split into East Coast and West Coast factions; he’s always been an astounding writer, but based on what I’ve read about this book (haven’t read it yet), this is where he’s really hit his stride. Leave it to you to ask all the right questions.

I'll be picking this up shortly.

I quite enjoyed PRIVATE CITIZENS and used it as a comparable when querying. Some agents told me it was a risky choice because the novel was "polarizing." That's how I knew I was on the right track.