Processing: How Rita Bullwinkel Wrote Headshot

The author on boxing, embodying characters, and "the gooey, weird stuff that time can do in literature"

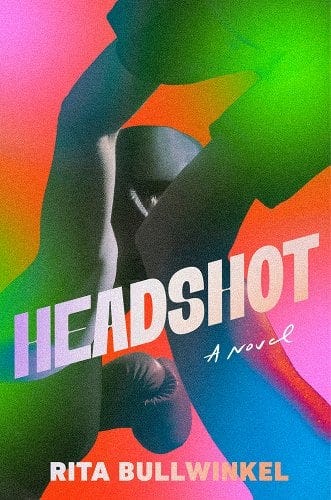

On a semi-regular basis, I interview authors about their writing processes and new books—you can find previous entries here—and this week I’m excited to publish an interview with Rita Bullwinkel about her excellent novel Headshot that comes out week. Headshot really blew me away. Like all good novels, it has to be experienced not summarized. But briefly, it explores the lives of eight young women in a youth boxing competition in Reno. The novel dips into the two characters’ minds in each match-up with an omniscient narrative voice that’s tender, sharp, humorous, and perceptive. We get the boxers desperate hopes as well as their past memories and eventual futures. It’s a great sports novel, but also much more than that.

I talked with Bullwinkel over email about structure, research, character, and “the gooey, weird stuff that time can do in literature.”

There’re so many things I loved about Headshot, but one aspect that impressed me from the start was the structure. It is both intuitive and surprising. The novel centers on eight young women competing for the Daughters of America boxing championship and the chapters go through the bracket match by match, focusing on the two women facing off in a given fight. This structure makes perfect sense for a novel about a sports competition, and yet I can’t think of many other novels structured this way. Did the structure precede the story or come about during the drafting process? Did you have any models in mind when structuring the book?

Oh gosh, Lincoln, these generous words mean so much to me, especially coming from you, an author who has written about a sports culture with such elegance and propulsiveness and grace! The structure came about during the drafting process. My first draft did not have the tournament structure. It was first person, from the point of view of a single girl boxer. It wasn’t right. It wasn’t the book I wanted to write. So I threw that draft away, and I found this tournament structure and started over. Once I had the tournament structure, the book wrote itself, in many ways. It’s largely the same from that first tournament structure draft. I’m not aware of any other books or films or works of art that utilize a tournament structure for character-driven narrative ends. I think the structure’s closest literary relative is a map, which is often included at the beginning of books, especially science fiction and fantasy books. It’s a visual to ground the reader in an unreal world. The space of the tournament has always felt very unreal to me. I think I needed a tether to earth, and with the tether of the tournament map I could take the narrative really far out in deep time and future space.

Formally, the chapters are composed of short flash sections that conjure the back and forth of a boxing match. The novel is narrated in a roving third person POV that is sometimes close and sometimes omniscient. I’d love to know about those decisions and how they changed, if at all, while you were writing the novel. For example, was there a time when the novel included first person sections?

Yes, the first draft of the book, which I threw away, was in the first person. I think of the third person narrator of the finished book as a Greek chorus of all the girl fighters that have come before, and the girl fighters that will come after the moment of the book and these eight young women boxers. I thought of the narrator as a collective of voices and experiences. Perhaps that is what god is? Hard to tell…

While the initial chapters go round by round, fighters by fighters, you take the freedom to loosen this structure as the novel goes on. I want to be vague and not spoil anything, but it made me recall George Saunders’s essay on pattern stories—centered on Donald Barthelme’s “The School”—and his suggestion that at some point the author has to move to another plane. (More specifically, he cites a possibly apocryphal Einstein quote: “No worthy problem is ever solved within the plane of its original conception.”)

If this question doesn’t risk spoiling anything, can you talk about adjusting the structure and scope of the novel?

I knew that the structure would have to fold in on itself in order for it to continue to build suspense. I couldn’t change some of the fundamental rules of the structure, but I could push the narratives further and further out into space, and provide a few of those brief, few-page intermission sections “Night” and “Deep Night.” I am honored that the book brought to mind Saunders’s essay on pattern stories! God, that’s a great essay.

I often feel that the manipulation of time is one of the must important qualities of fiction. Headshot is a novel that does a lot with time, dilating to stretch out a moment or quickly summarizing a round, then flashing backwards or forwards. What’s your approach to time in this novel, or in your fiction in general?

I completely agree that the ability to fuck with time is unique to the medium of fiction. In film, even when we’re in flashbacks, we’re still moving forward linearly. In fiction you can fold time on itself, layer it, make it longer or shorter both experientially and narratively. It’s one of the most affecting things about the medium, and certainly what affects me the greatest as a reader, so I knew I wanted to write a book that deployed the gooey, weird stuff that time can do in literature. My approach to time in this novel had to do with seeing if I could make the reader feel like they were inside the space of a boxing match, which can feel fast and slow at the same time. In general, I find exercise has a way of making time wiggly. I wanted to see I could write a book with wiggly time, too.

How did research—in or out of the ring—inform the novel?

I am not a boxer, but I was a competitive youth athlete. I co-captained a top 20 ranked division 1 water polo team. Many of my teammates and opponents went on to play professionally in Europe and Australia, where they have pro women’s leagues, and there was a time when I knew everyone on the American women’s Olympic team, because I had either played with them, or against them. This summer Olympics will likely be the last year I know some of the players, and they are elder statesmen at this point. Many of my experiences as a competitive youth athlete shaped this book. I wanted to write about the space of the tournament because I had lived inside so many tournaments. Boxing was an ideal setting to unleash the psychological portraiture I was interested in because so much of the sport (the lighting, the gear, the ring) already feels like theater. Also, because it’s one on one, I could create non-verbal dialogue between characters in a way that I couldn’t with a team sport. I think there are a lot of shared realities in youth women’s athletics no matter what sport is being played. I learned almost everything I know about boxing from YouTube videos that had three or four views that young girl boxers uploaded to document the changing of their form over time. This documentation resonated with me. I did this, too. There were once thousands of hours of footage of me shooting free throws, running, treading water, all recorded in an attempt to perfect my form. It’s a common training technique. When I saw the girls in those videos I saw myself in them and I knew I could set the book in the world of boxing. My hope is that even though I am not a boxer, boxers will find authenticity in this book. Ginny Fuchs, one of the world’s best boxers, generously gave the book an early read and blurbed it, which meant the world to me. My sincere apologies to any boxers for things I got wrong. The fault is obviously my own.

Even as the characters are bound by boxing and age, they feel quite distinct. The novel is written in the third person, but the voice—or at least mindset—of the eight different fighters comes through. Did you have any particular practices to get into the head of a given character when writing?

I relate to the idea that writing is like acting in that all the characters are both me and not me, and in order for me to embody any character I have to believe that I could be them, or I am them, on an alternate plane. Headshot has a large cast. I had to give all eight of the main characters portions of my own lived experiences in order to embody them. This book doesn’t contain any characters that were difficult for me to embody. When I have written a difficult character before, a serial rapist, for instance, I became quite sick. There’s probably a better, less invasive way to embody character on the page, but I haven’t found it.

In general, can you talk about your writing process? Do you have any habits or superstitions? Or does it vary by project?

There are periods of time when I write a great deal and periods of time when I write nothing. When I do write, I mostly write quickly.

The novel doesn’t have any dialogue, I believe. Can you talk about that decision?

Omitting dialogue was not something I was conscious of doing while I was writing, but it makes sense that nobody verbally speaks to one another because the entire book takes place while the characters are boxing. However, there is some remembered and future speech, without dialogue tags, in the fighters’ minds’, I believe.

I’m always curious about the overall process of writing a novel from first draft to publication. Anything you are willing to share about how the novel evolved over the course of drafting and revision?

My brilliant Viking editors, Allie Merola and Paul Slovak, pushed me to expand one of the last fights, which did the book a great service. They were also brilliant at helping me perceive where the repetition in the book was powerful, and where it was ineffective. I am forever in debt to both of them. They made the book much, much better.

Any last advice you’d give an aspiring novelist working on their debut?

Write in the way, and with the practices, that make you feel powerful. The world is a better place, and you are likely better, after you have spent time alone in your mind, trying to figure out what haunts you.

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.” Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

I also have a story adapted in The Werewolf at Dusk, a new graphic collection from David Small out this month from Liveright.

Very interesting stuff. The competition bracket is a pretty common structure in Japanese anime. Basically each fight dives into the background and motivations of the current antagonist, reinforcing the themes of the story and providing the context for the conclusion, where the protagonist learns something from each opponent as they move towards the final confrontation.

I had this book on my radar but after learning about this book's structure I'm very intrigued. I might have to pick up a copy.