Processing: How Martin Riker Wrote The Guest Lecture

"A lot of good literature comes from writers figuring out how to take the crappy parts of their lives and turn them into something interesting."

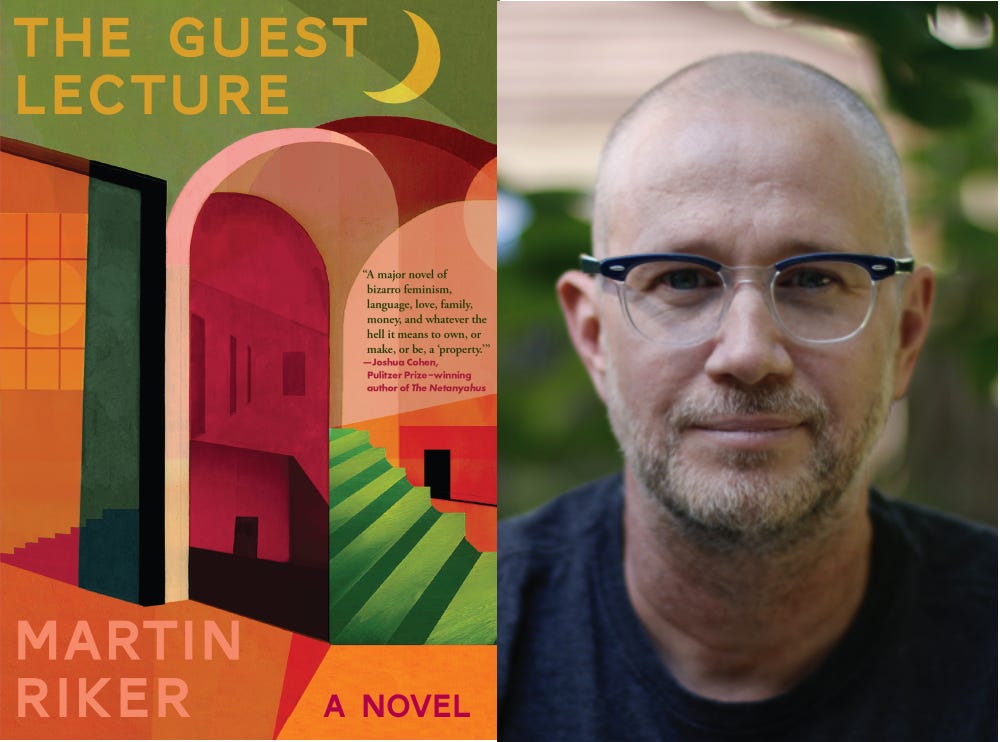

On a semi-regular basis, I interview authors about their writing processes and craft—you can find previous entries here—and today I’m really excited to publish this interview with Martin Riker, whose excellent novel The Guest Lecture came out this week. The Guest Lecture was one of those magical books I plucked at random from my review copy pile and was instantly taken with. We follow Abby, an economics professor lying awake at night in a hotel room and anxiously thinking about the guest lecture she has to give the following day. The novel stays entirely in her head with no external action. It’s the type of novel that seems like it shouldn’t work. But Riker pulls it off and produces a deeply funny, moving, and thought-provoking book.

I reached out to Riker over email, and we chatted a length about literary form, insomnia, and how writers can take “the crappy parts of their lives and turn them into something interesting."

The Guest Lecture is one of those novels I love in part because it could only be a novel. More or less everything that happens in the book takes place in the mind of Abby, a professor laying awake and anxiously thinking about the economics lecture she has to give tomorrow while discussing it with an imagined version of John Maynard Keynes.

I’d love to hear how you struck on this central conceit. Was the novel always planned as taking place entirely in interiority? Or did you settle on that during the drafting process?

The overall weird way the book comes together happened really gradually, but it was always an interior monologue, yes. It was somebody up all night moving back and forth between different mental spaces, and then also between the present and the past, hope and despair. A lot dialectical and associative motion, in other words, but more choreographed than a typical stream of consciousness. More like a story. My deep background is actually as a musician, and as a writer I think more in terms of movement than anything else, the particular way a story is going to remain in motion and why that sort of movement, whatever it is, is going to be interesting.

So it's an interior monologue, and specifically it’s an insomnia monologue, an even narrower genre. But as it happens, a number of my favorite novels belong to this genre, and each does something really different. Three I had in mind while writing The Guest Lecture were Vedrana Rudan’s Night, Alasdair Gray’s 1982 Janine, and Beckett’s Company. It seems everything I write starts with loving something I’d read, but in this case it was not just one book (as it was with my first novel, which is a “retelling” of Robert Montgomery Byrd’s 1836 Sheppard Lee, Written by Himself) but a lot of different books each of which added something different to the mix. What was important about the three novels I just listed wasn’t just that I loved how they handled this form, “the insomnia novel,” but that they each handled it so differently. That variety meant that the rules of the genre were loose, up for grabs, and there was lots of room for invention.

Although the novel is in one sense stream of consciousness, there is plenty of movement and structure to her thoughts. “Plot” in a sense. How did you approach “plotting” in this novel?

That was the fun part! Well, they were all the fun parts. There are four different types of text that the book alternates between, or I will call them four types of space. There are essay spaces, story spaces, space spaces (actual descriptions of rooms), and eventually there is also the space of dream. Each one has a different texture and language of its own, and when you’re inside one of these spaces, it offers you its own way of being in the world (in language). I am a different person when I’m reading an essay than when I’m reading a short story; my engagement with the world feels different. So, in a very practical way, when you move between the book’s different “spaces” what you really move between is different ways of being. The book has a lot of large and small craft-strategies for generating energy and momentum—transitions, foreshadowing, that kind of stuff—but this movement between ways of being is more than just a strategy, it’s one of the things this book is actually about. How life is like that.

In terms of theories of the novel, I’m a Bakhtin guy. I want novels to be experiences of polyphony, multiplicity, a non-hierarchical stew of ideas and forms. Our culture is mostly monologic and didactic, but the special opportunity novels offer is the creation of a state of play where possibilities are put in motion with one another.

When we first emailed, you called yourself “a card-carrying Shklovskian formalist.” Could you talk more about what a formalist approach means to you and how it manifests in this novel?

I think I just meant that I am wonkish and love to talk about literary form, but I will try to give you a better answer.

For about ten years—basically my thirties—I was the associate director of Dalkey Archive Press, and worked on a number of books by the Russian Formalist Viktor Shklovsky. Perhaps my favorite is Energy of Delusion, in case anyone is interested. A Shklovskian formalist, a Russian Formalist in general, is different from an American New Critic in one very important way. The New Critics were a variety of formalists who wanted to study form free of outside considerations. At least that is the received understanding of what the New Critics wanted. The creative writing workshop model, which has roots in New Criticism, is often criticized for this, and for a while academics were pretty down on formalism for the same reason. But the Russian Formalists saw form as an expression of experience, and as historically and culturally derived. It’s like Guy Davenport’s “every force evolves a form,” where form is understood not as a stand-alone aesthetic structure, but as the unique expression of a force in the world. In other words, literature and life, form and content, are in constant conversation with one another. Shklovsky was a structure nerd who wrote sentences like “When works of art are undergoing change, interest shifts to the connective tissue,” but he also wrote, “Give everything a cosmic dimension, take your heart in your teeth, write a book.”

Another piece of trivia about me is that my master’s thesis adviser was David Foster Wallace (at Illinois State University, where I had gone to work at Dalkey Archive Press). This is relevant because of a conversation we once had, where David asked me how I could even enjoy reading, given that I was such a formalist, always wanting to talk about how a story was made rather than the emotional arc or whatever. This was a surprising question coming from a such smart person. First of all, I love artistic form. I don’t just “find it interesting,” I love the adventure of how artists put things together, how art takes the stuff of the world and figures out new ways to see it. Second, I see no reason at all why the experience of form and the experience of “content” should be mutually exclusive. As it happens, I am extremely susceptible to emotional content. I am the guy who cries at TV commercials, which drives my son crazy. But I have also read Thomas Frank’s The Conquest of Cool, about the history of the advertising industry, so I understand the narrative moves the commercial is making as well as the historical traditions of advertising that it draws upon. This is the stuff that interests me.

Last thing I’ll say about Wallace—who was a friend and whose loss was devastating—is that his emphasis on empathy never spoke to me. Obviously, empathy is a really foundational part of what makes novels interesting, but for me it’s only one of the many possibilities constantly at play. It isn’t “the point” of the novel form. Namwali Serpell has that really good essay about this. The point of art, for me, is very simple, and comes from Shklovsky: “Art is a means of experiencing the process of creativity.”

[Note: you can read Serpell’s excellent essay here.]

One of the challenges of an interior-driven novel is risking all telling and no showing (to use the old MFA cliché). That there isn’t action or setting for the reader to visualize. You get around that in part by having Abby use the “memory palace” method of rhetoric—which originates with Simonides of Ceos—where Abby mentally moves through her house as she thinks thought the parts of her lecture while accompanied by John Maynard Keynes. Is this a method you use yourself? And how did you settle on this tactic in the novel?

One of the other books that served as a model for aspects of The Guest Lecture was Georges Perec’s wonderful Life, a User’s Manual. Perec’s novel chronicles all the lives lived in a Parisian apartment building, but the way he proceeds is by describing each room when it is empty, all the stuff in the room, the detritus of life in great detail, then pivoting to tell the story of the person who lived there. As an effect, it is both haunting and warmhearted, a surprising combination. Anyone who’s read The Guest Lecture will immediately recognize how that particular narrative strategy found its way into my book, but also how differently it’s handled, and to very different effect. Abby, the narrator, uses Simonides’ loci method to mentally move through the rooms of her house, setting herself down in each room to remember whichever piece of her speech she has mentally secreted away there. In structural terms, what is presented as a story-driven mnemonic doubles as a plot-driven conceptual hinge that allows the book to quickly pivot between essay spaces and story spaces and space-spaces. But it also pulls in the book’s emotional crises, because this house whose rooms Abby is describing to herself is also a house she is about to lose, and is metonymic for everything else she has lost or is losing. So, it’s a formal technique, but it’s also a direct line into the heart and guts of everything the narrator is going through.

Perec’s work in general has always been very important to me. It showed me how novels can create different spaces of experience—the stuff I was talking about earlier—and how the orchestration of these spaces can constitute a kind of movement that is not exactly “plot” but that does some of the same work that plot can do.

One novel I thought about while reading The Guest Lecture was Nicholson Baker’s The Anthologist, which is of course very different but also a voice-driven novel about an academic obsessing about their field. (In that case, formal poetry.) I remembered Baker claimed to have walked around his house recording himself lecturing in his narrator’s persona to discover the voice. This may be a weird question, but it made me wonder if you had any unique processes for this book. For example, did you compose any of it while lying in bed to mirror the character? Late at night?

I am happy to say I have actually read that book! Was I thinking of it when I wrote this one? I’m not sure. The point of comparison I would draw when I think about it now, though, would be Baker’s handling of intellectual material (ideas, theories). The “status” of ideas in a novel is something I think about a lot, in terms of my own work and others’. One thing I loved about The Anthologist was that the narrator’s thesis—which I remember as being a kind of conservative argument for the superiority of rhyming poetry—seemed at once kind of loony (to me) but also ardently and artfully thought-through. There was a sustained ambiguity around the status of the narrator’s “ideas,” in terms of how the reader was meant to “take” them, that I thought showed brilliant restraint on Baker’s part.

a lot of good literature comes from writers figuring out how to take the crappy parts of their lives and turn them into something interesting

To answer your actual question: I did lay in bed late at night working on this book, but your question has the causes and effects reversed. I have always thought that a lot of good literature comes from writers figuring out how to take the crappy parts of their lives and turn them into something interesting. As a person who experiences periodic insomnia, writing a narrator who can’t sleep seemed like a really good use of my time. Then, whenever I’m up at 3am, I don’t just have to feel bad about myself, I can think, This is all research for my book! It doesn’t make my insomnia go away, but it does make it seem less useless. And actually this is also an important part of what The Guest Lecture is about: Abby is faced with a sleepless night and has to decide what to do with it. She wants to do something practical with it (practice her speech) but her mind won’t entirely allow that. The essential drama of the book is the struggle of her imagination to make the sleepless hours useful, which she does in part by trying to approach the workings of her own mind with playfulness and openness.

There’s been a lot of literary discussion over the last decade or so about the border and blurring of fiction and non-fiction. Most of that has been focused on “autofiction” and having autobiographical elements in fiction. The Guest Lecture has a different kind of fiction / nonfiction blurring, in that much of the novel is devoted to Abby’s economics lecture. As someone who is also a critic, do you have thoughts on the distinction between fiction and nonfiction? Was blurring that boundary something you set out to do?

I really appreciate the distinction you’ve drawn here, and I think you’re right, the book takes up some of the prevailing questions of this literary moment, but takes them up in its own way. Another recent book that is a little like The Guest Lecture in how it navigates this movement between fiction and nonfiction (or nonfiction as fiction) is Joshua Cohen’s The Netanyahus, and he and I discuss this question in an interview I did with him here, in case that’s of interest.

On a different note, I’ll say that the most important similarity between my criticism and my fiction is that I don’t write to tell people things I know already, but instead to learn about things I’m interested in. The books I pitch for review are generally books by writers I’m drawn to but haven’t gone deeply into already, and writing the review becomes an opportunity to read all of their work and spend time in the space of their writing. This is not the only reason I enjoy reviewing books, but honestly, it’s the only one that really matters. And the same is true of The Guest Lecture. Some of the knowledge and ideas that Abby works her way through in the course of the novel are things I knew about before—the history of rhetoric, for example—but most of it is stuff I was interested in learning about. And this is very important, because writing things I already know is kind of boring to me, and I’m not sure I’m any good at it. But learning about new things by way of a writing project is very meaningful, and my best writing is always driven by this energy of discovery, this process of figuring out what I think through the writing itself.

John Maynard Keynes himself appears as a character in the novel, albeit in Abby’s imagined version of him. I’m curious how you approached the voice of the Abby-insomnia-Keynes character. How much or how little did you worry about fidelity to the real Keynes’s voice?

Very little? I did a lot of research all throughout this book, and in the course of that I listened to recordings of Keynes, but everything about Abby’s Keynes is really just Abby. I mean, it is importantly not-Keynes. She provides facts about him, she states opinions about some of his ideas, but it’s all in a novelistic context. The most important characteristic of her imaginary Keynes is how he reflects back on her, and in this sense fidelity is not just a secondary consideration, but is something the novel might at times purposefully transgress in order to accurately render her subjectivity.

Do you have any set habits in your writing processes? A time of day or a location you always write? Any practices you do to get into the right headspace?

Writing is wonderfully fun for me almost all the time, and so much of that pleasure is the physical act of doing it. It is almost never a chore, and requires nothing more than sitting down with enough time to think about the work without distraction. Preferably at least a two-hour chunk, ideally early in the day, because after 2pm my brain is useless. I am not the most productive writer in the world, and certainly not the fastest. But part of that is that I do a lot of other things: teaching, reviewing, parenting, publishing other people. If you ranked my life activities in terms of time-spent, my own writing would be pretty far behind parenting and teaching and publishing other people.

In addition to being a novelist, you’re a critic and co-founder of the fantastic literary press Dorothy. How does your criticism and editorial work shape your writing? And vice versa?

Well I mentioned earlier that before Danielle and I started Dorothy, I’d worked in publishing at Dalkey Archive for about ten years, so really I came of age as a literary person more in the role of publisher than author. One result is that my relationship with literature has always moved in several directions at once, but it all feels like parts of a whole to me, the writing and the reviewing and the publishing. To my mind these are all similarly creative activities, and even on a technical level, in terms of craft, or praxis, they have more in common than not. I’ll give you an example.

One of the roles I had played at Dalkey Archive was to oversee publicity, and once every six months I would travel from Illinois to New York to meet with review editors. Because I was a well-read person, I developed real friendships with review editors at a few of the major newspapers, who were happy to sit around talking books rather than being constantly pitched at. When I left Dalkey, I wrote to these people to let them know, and two of them wrote to say they’d miss our conversations because it was fun to talk with a publicist who had interesting ideas about books. I said, Funny you should say that, because I was hoping to get some reviewing work! And that was how I got my first reviewing work for the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal.

I hadn’t done a lot of reviewing before this, nor had I published almost any of my fiction, but suddenly I had assignments to write 1200 words for 4 million people. I think these original review assignments were the most important moment for my development as a writer. The pressure I felt to do a good job, and the particularity of the audience for whom I was writing (I pictured my mom as the reader), forced me to massively up my game in terms of concision, and narrative tension and pull, and the freshness of transitions, all that stuff. I hold multiple degrees in creative writing, and that was probably all useful to me in generative ways, but the shock of suddenly writing for a real and large audience, and the creative discipline required to pull that off, was a clear turning point, not just for my critical writing but for my fiction as well.

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.”

Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

Ugh, I loved reading this. I’m struggling with form presently and this edition of the newsletter was highly inspiring. Thank you.

Thank you for a great interview. I am experimenting with form in my current project, and as Jasmine says below, this is full of gold.

On another front, my belief in serendipity as my personal creative force/muse is confirmed once again. Your most recent post lead me to my bookcase to pull out Marcel Schwob’s Imaginary Lives. Inside that little book I had folded up Martin Riker’s WSJ piece on Schwob, which lead me to buy the book, and when I reread the piece I saw at once I reread, how to approach/structure my current work-in-progress. I had skipped over this interview when it was initially published. Scrolling down after reading comments on your latest post, I realized the interview was with Riker.