Processing: How Julia Elliott Wrote Hellions

The author on genre-bending, psychedelic Southern summers, and lyrical language as "the magic key that enables you to slip between worlds"

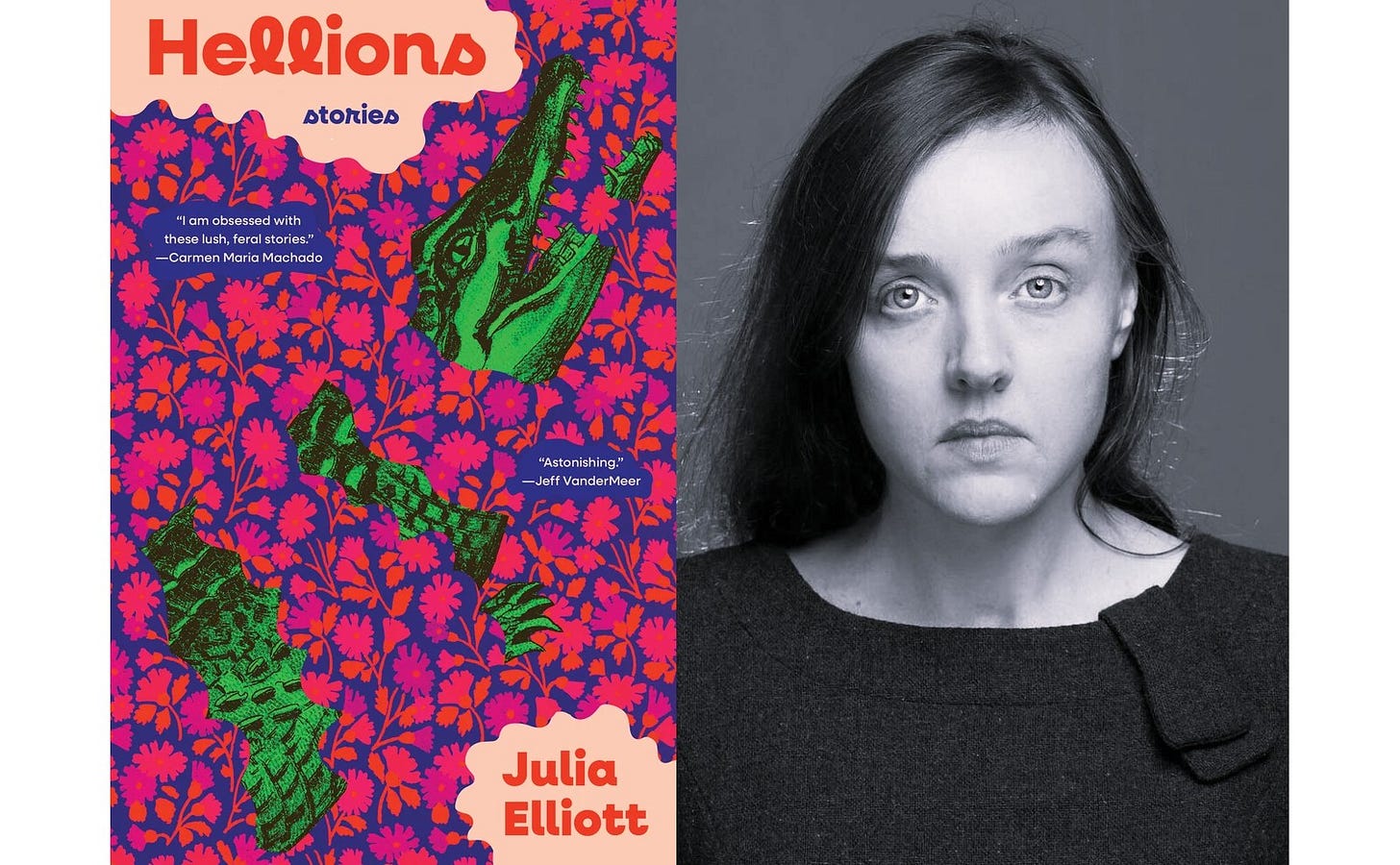

On a semi-regular basis, I interview authors about their writing processes and the craft behind their books. You can find previous entries here. This week, I’m excited to be chatting with Julia Elliott about her excellent new story collection Hellions. I first encountered Elliott’s work when I was assigned her novel, The New and Improved Romie Futch, to review for the NYT in 2015. (My first assignment for the NYT, in fact.) After reading that novel and her first story collection, The Wilds, I knew I’d be a lifelong fan. Elliot’s work combines many things I love—lush Southern Gothic prose, unruly characters, clever science fiction concepts, strange monsters—with a general sense of wildness and adventure on every page. Elliot’s new collection features eleven lyrical and feral stories that romp between historical fiction, Southern realism, fairy tale retellings, and more. The prose is both poetic and strange and the stories equal parts moving and riotous. It is the best story collection I’ve read so far this year.

I talked with Elliott over email about constructing her new collection, bending various genres, and lyrical language as “the magic key that enables you to slip between worlds.”

Many of the stories in Hellions might be described as not just “genre-bending” but “genre-colliding.” “Erl King” combines fairy tales and campus fiction; “Moon Witch, Moon Witch” mixes science fiction, realism, and a sort of epic fantasy; “Bride” is both historical, religious, and Gothic; etc. I’ve very curious about your relation to “genre” in general. Do you start a story knowing what genre(s) you want to work in? Or is that something you prefer not to think about and to leave to readers and critics?

Reading “The Lottery” by Shirley Jackson and “The Metamorphosis” by Franz Kafka in high school stirred an early awareness that the distinction between “literary” and “genre” fiction was bogus and that “literary realism” was never going to be my thing. It wasn’t until I started reading George Saunders’s fiction in the New Yorker in the 90s, however, that I started formally categorizing genres and sub-genres and thinking more strategically about the literary effects of combining them and the political implications of challenging the “hegemony of realism” (I’m putting that in quotes because it sounds pretentious). I use genre as a trope to voice ineffable experiences and philosophies—sometimes consciously, other times intuitively. As a grad student, I studied experimental fiction, but also literature from the medieval and Renaissance periods, eras when magic and science were often indistinguishable, when one could find a recipe for cough syrup right next to a spell to keep incubi from visiting at night. My story “Bride,” inspired by medieval female mystics like Margery Kempe, intuitively evokes a high Gothic atmosphere and the surreal religious visions of a starved, ecstatic nun. On the other hand, I made a very conscious decision to meld seemingly incongruous genres in my story “The Maiden,” in which a group of small-town teens discover the transcendent magic of an outcast girl named Cujo who hexes kids by performing supernatural trampoline stunts. The story begins with a mix of Southern Gothic and magic realism, but when Cujo shows her true form, I took a risk and incorporated some pretty outlandish elements from high fantasy—an epic mode that hearkens back to Renaissance works like Edmund Spenser’s The Fairie Queene.

One particularly delicate balancing act in many of these stories is between (broadly speaking) realism and fantasy. Often the stories are ambiguous about how much of the surrealism or the fantastic is “actually” happening. I love that sort of ambiguity myself and also know how difficult it can be to achieve. How did you approach that balance?

The father in the story “All the Other Demons” is an exaggerated version of my own dad, a weird, verbose man who loved to spellbind his children with strange tales and arcane lore, patchwork narratives drawn from whatever sources he needed to hold our imaginations captive. As I grew older and started performing my own version of the charismatic raconteur, my father said I suffered from a “hyperbolic condition,” a genetically inherited illness enhanced by a steady diet of tall tales. By the time I started writing poetry in high school, I was possessed with the power of language, and my main goal was to enchant readers with streams of words—never mind the subject matter. This language-driven approach to writing naturally drew me toward works of magic realism, Surrealism, and the absurdist extremes of Southern Gothic—genres in which the border between the “real” and the “fantastic” is blurry and lyrical language is the magic key that enables you to slip between worlds—whether you’re evoking a demon from another dimension or attempting to convey the psychedelic effect of a dog day in South Carolina, with its supernatural humidity, shrieking cicadas, and lush vegetation.

Can you talk about how Hellions came together as a collection. How did you decide what stories would appear in the collection? Were stories written specifically to work with existing ones and/or were there stories that were cut because they didn’t seem to fit with the others?

Because short stories allow me to chase a wide range of obsessions and experiment with various genres, voices, and narrative forms, I don’t limit myself with themes while writing them. Once in the past, when attempting to write with a larger conceptual framework in mind, I produced a few forced, uninspired stories before abandoning this imposed limitation. I’ve written and published a lot of stories since The Wilds appeared in 2014, and I’ve even compiled one or two “collections” that didn’t quite cohere. In 2023, I realized that my story “Hellion,” published in the Summer 2018 issue of The Georgia Review, offered the perfect concept for pulling in a range of stories about rebellions girls and women who “long for the otherworldly.” “Hellion,” a term I heard often in my youth, is an impish, misbehaving creature—usually a child—who has the Devil in them and resists being domesticated by polite society. While half of the stories in Hellions explore the uncanniness of feral girlhoods, the others revolve around the archetype of “the witch”—liminal women who lurk along the border between the real and unreal.

The stories in Hellions use many different craft techniques—including using almost every POV, even the rare first-person plural in “The Maiden”—yet never in a showy way. These are stories first, not experimental showcases. Still, I’m curious how craft questions like POV or structure drive your stories. Do you come up with the POV and structure before writing a story or do such decisions arise during the drafting?

While the structures of my stories usually take shape during the drafting and revision process, I almost always decide which POV I’ll use before starting a draft. Most of the stories in Hellions are told from first-person or third-person limited perspectives, providing access to a single female character’s psyche with various levels of intimacy. Interestingly, the only two stories told from male perspectives use rarer POVs to approach mysterious female characters from a distance. “Flying” uses second-person to place the reader into the mind of a medieval man from a small village who chases a shape-shifting enchantress through a primeval forest. This point of view enables the reader to share the man’s bafflement as he slowly begins to understand more about this woman. Similarly, “The Maiden” uses first-person plural to capture the collective curiosity of a group of small-town teens who contend with the mystery of Cujo, a girl who performs hexes with outlandish trampoline stunts. As the story progresses, the larger collective consciousness of the POV narrows to that of four characters, the only kids who begin to comprehend Cujo’s true nature.

There are many things that stand out in your stories but foremost might be the lush and lyrical language. Your pages are packed with beautiful lines and strange, lovely images in a style that is often called “Southern Gothic.” Your stories too are typically set in the South, where you life. What’s your relation to “Southern Gothic” and how do you see the role of “Southerness” in your work?

As explained above, my father came from a long line of garrulous, yarn-spinning Southerners who infected me with a “hyperbolic condition” as a child, the desire to hold people captive with intoxicating language. Part of the Southern Gothic arises from social and familial hauntings—repressed ghosts oozing up from stagnant water, skeleton’s moldering in closets, antebellum and Jim-Crow-era brutalities that linger in architecture and cotton fields, personal trauma and politics. But there is also something ecological about the Southern Gothic that is epitomized by the endless psychedelic summers—lush and rank, loud with shrieking insects—maddening summers that go on and on and make you wonder if your brain has been infected by some interstellar parasite you caught from a stagnant lake, the black water of an eerie swamp, or simply by breathing in the muggy air.

I always think of the “Southern Gothic” as one of these great literary traditions in which writers are speaking to each other across time. And that isn’t the only tradition your stories are working in. Hellions draws from various traditions like fairy tales and even makes explicit connections. “Erl King” alludes to Angela Carter’s classic story “The Earl-King” from The Bloody Chamber and the back of the book contains notes on each story, showing various allusions or references. I realize this is a very vague question, but how do you see your work relating to existing literature and traditions?

I appreciate all kinds of fiction and love many realist books, but personally, I feel most akin to genre-benders, weirdos, fabulists, Surrealists, and magic realists of all stripes, writers ranging from Agnes Blannbekin, a thirteenth century Austrian mystic who claimed she repeatedly ate the foreskin of Christ, to contemporary practitioners of the fantastic like Karen Russell, Sofia Samatar, and George Saunders. I love Angela Carter, Leonora Carrington, Franz Kafka, Carson McCullers, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Octavia Butler, Carmen Maria Machado, Nathan Ballingrud, Jeff VanderMeer, Nalo Hopkinson, Margaret Atwood, Barry Hannah, Paul Beatty, Jorge Luis Borges, Thomas Bernhard, Percival Everett, Diane Cook, Brian Evenson, Shirley Jackson, Ben Okri, David Mitchell, Joy Williams, Mikhail Bulgakov, Daisy Johnson, Nikolai Gogol, Donna Tartt, and hundreds of other odd bird writers who evoke the strange with magic words that restore my sense of wonder in an increasingly alienating world. After I submit this, I will think of other crucial writers who belong on the list I just casually rattled off. I would put your work in this category too, Lincoln, as I am a fan of Upright Beasts and The Body Scout and cannot wait for Metallic Realms.

And lastly, if you don’t mind sharing, what are you working on next?

I’m writing an absurd, psychedelic, sci-fi rendition of “The Princess and the Frog,” an amphibious novel infested with psychonauts, tech tycoons, and otherworldly bullfrogs.

If you enjoy this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout—which The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent”—or preorder my forthcoming weird-satirical-science-autofiction novel Metallic Realms.

Thank you! New writer for me.

Well I'm definitely picking this one up!