Processing: How Elisa Gabbert Wrote Normal Distance

The author on sentence-thoughts, constructing poems, and the eternal themes of “boredom, death, and suffering!”

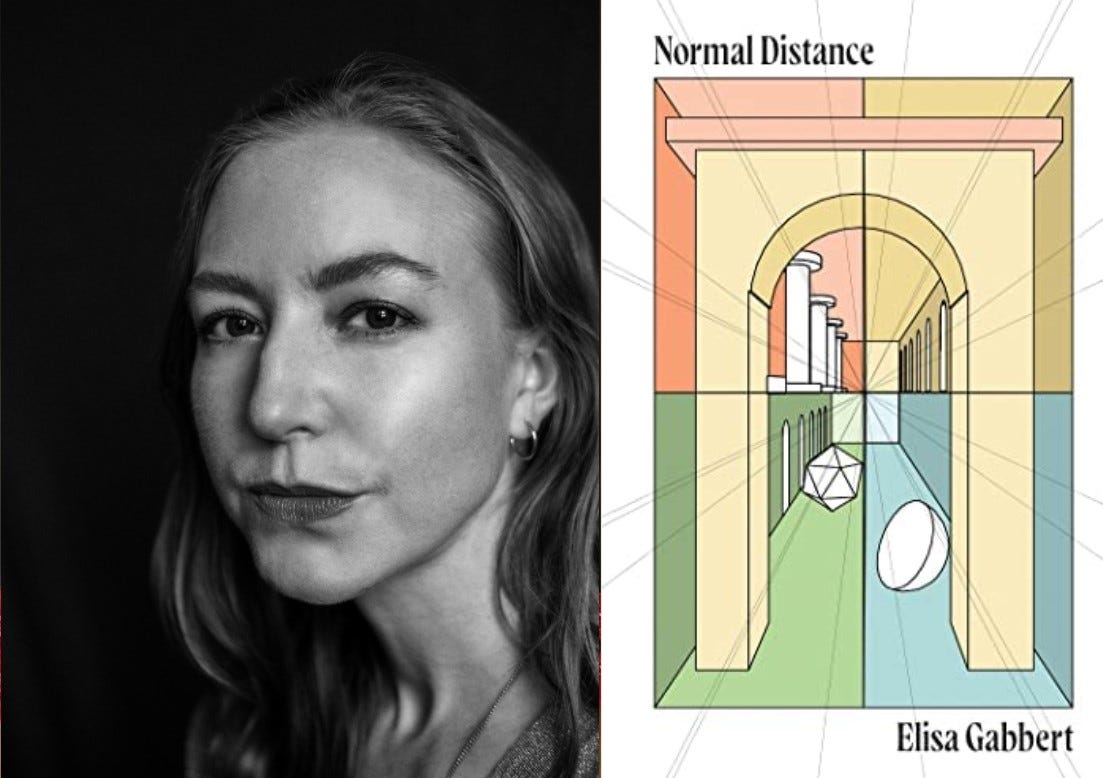

On a semi-regular basis, I like to interview authors I admire about their writing processes. This week I was excited to chat with one of the smartest people I know: Elisa Gabbert, whose new poetry collection, Normal Distance, I devoured on recent subway rides to and from work. Gabbert is the poetry critic at the New York Times, a fantastic and deeply thoughtful essayist—I interviewed Gabbert about her last essay collection for BOMB if you’re interested—and, of course, an excellent poet. The poems in Normal Distance blur the lines between these roles, reading as hybrid critical essays and lyrical poems. Most are written in an aphoristic style, with Gabbert meditating on different topics like boredom, sex, and madness in lines that are by turns thought-provoking, imagistic, arresting, and hilarious.

We chatted over email about writing poems, writing tweets, and the eternal themes of “boredom, death, and suffering!”

The poems in Normal Distance blur the line between poetry, philosophy, essay, and comedy, but if one thing unifies them it’s form. Most of the poems are written in short one to two sentence stanzas separated by line breaks. On the page—and I think in style—they read not unlike a collection of aphorisms or one-liners, although of course they’re more than that.

So my first question is about how you wrote these poems. Did you write these one-liners (if I can call them that) in sequence or were they written separately and then compiled into poems?

Both! The earliest poems in this collection were collaged out of these one-liners or aphorisms I had already written. “New Theories on Boredom” is a good example – it’s like every thought I’ve had about boredom over five to ten years, and then I tried to arrange them in such a way that it feels like the thoughts occurred in that order. This is one of the magical things about writing, I think – you can cut out all the empty time you had to live through between having interesting thoughts and just put the interesting thoughts down. After I had composed a few poems that way, I sort of internalized the form and rhythm and could write them from scratch, as it were, or in some cases just starting with one or two one-liners I felt had potential and expanding from there. And then of course there are the shorter, fifteen-line poems which completely break the pattern of the longer poems, though I did set a rule for myself that each of the five stanzas in those poems had to be self-contained, no enjambment between stanzas, which makes them of a kind with the longer poems in a way.

You and I are both what the kids call “posters.” That is, we spend a lot of time on Twitter. Twitter is obviously [checks notes] a bit chaotic right now and I don’t want to ask you about Musk or anything like that. However, at your book launch I believe you said that many of the lines in this book were taken from your tweets. Can you talk about that process? When you tweet a killer line, do you know it will be used later in a poem?

I don’t typically bother to write something out – either in a notebook or on Twitter, which has always served as a kind of public notebook for me – unless I think it’s an interesting enough thought or line to commit to some level of history, maybe only my own history (because once I write a thought down, as a sentence, I might remember it forever). And often I keep thinking about these sentence-thoughts and want to do something more with them. I also often have the experience of finding that something I thought in the past, when I encounter it later, by flipping through a notebook, or through a Twitter search, is more profound than any thought I’ve recently had. I think the distance helps.

Moving from the individual poem to the collection, how did you compile the manuscript for Normal Distance? Were the poems written to be published together? Were there poems that didn’t fit that you’re saving for the next book?

My husband, John, who you know as a tall and handsome raconteur [editor’s note: true], told me several years ago he thought I should publish a book of poems next. I had only written a handful of those funny/philosophical collage poems so far, but I’d performed them at some readings and people seemed to like them. So I thought, OK, let me try to write a book of these. I was writing lots of essays and such at the same time, so it ended up taking about five years. The shorter poems were the last ones I wrote before I decided it was finished and sent it to my agent.

As for the next poetry book, I don’t know if there is any next poetry book (skull emoji). I haven’t written a poem this year. It’s not unusual for me to go a year or more without writing poems, so I may write poems again someday – I hope I do – but when I’m not writing poems it always feels like I might be done forever.

Do you have any particular quirks to your writing process? Any particular routines you have to do?

Oh yes, though for me prose requires these types of processized, almost superstitious rituals more than poetry does. I have to take a lot of notes, and usually I’ll start a document just for these notes and add to it over weeks or sometimes months or years before I decide I’m ready to do the writing proper. Then I need to declare a day, like declaring a war, that I am officially going to write, and on that day I like to write as much as possible, thousands of words. And then I need to read over what I write a lot and make all the tiny finishing changes that are so important to me, shades of meaning changes, rhythm changes. I like to do some of this latter stuff, the last 1%, a little buzzed. Again, the benefit of distance!

Reading Normal Distance, I had the impression of a great mind thinking over topics again and again. Certain ideas recur, for example our relationship to boredom. There’s the poem “New Theories on Boredom” of course but boredom appears in many poems. “You’re going to die of something. // I hope I die of boredom in my sleep” in one poem and in another “I feel most myself—most trapped in my self—when I’m bored.” These recurring themes really unify the collection, making each poem feel part of a larger whole. Did you go into the collection planning to muse on these particular topics (boredom, death, suffering, etc.)?

One of the things I am looking for in an encounter with any kind of art is just the impression that someone has thought about it a lot. This is ridiculous, but the realization came to me while I was watching the recent Top Gun sequel. It just felt like people thought about that movie a lot more than they had to, and that’s so refreshing. I love the feeling that someone has spent a lot of time on something, and I love projects that feel like someone has been saving up ideas their whole life to put into them. Like the long Wong May essay in the back of this anthology – that essay feels like it contains every interesting thought Wong May has ever had about translation, poetry, life in general. It’s so rich.

That said, I didn’t really decide ahead of time what topics I was going to spend that much time with – those are just the topics I always return to by default. Boredom, death, and suffering!

One of the things I am looking for in an encounter with any kind of art is just the impression that someone has thought about it a lot.

Many of these poems read as poetic essays of a sort, by which I mean they meditate on different topics. You signal this with your titles: “About Suffering.” “New Theories of Boredom.” “Madness.” In addition to being a fantastic poet, you’re a tremendous essayist—everyone please go read The Unreality of Memory—and I’d love to hear how you consider these poems in relation to your essays. Are they companion pieces in a way? Do you see the poems crossing over into the essays and vice versa?

Thank you so much Lincoln! I definitely hold myself to different standards when I’m writing nonfiction – I feel a lot more allegiance to reality – but I like to bring essayistic qualities into my poetry and poetic qualities into my essays. “Poetic” is a fraught word though, and often when a novel or memoir is described as “poetic” that’s a sign that I’m not going to like it, it often seems to be code for “overwritten.” When I think about poetic qualities in prose I’m thinking more about mystery and surprise.

Writers and thinkers of various sorts appear not infrequently in these poems. (“I’m trying to decide if Wittgenstein was sexy. It’s not obvious.”) I’m curious about your approach to intertextuality (sorry to sound like a professor) in these poems.

I think I get very bored with myself and my own mind and life. You know how a gathering can feel boring and then suddenly someone new walks in and changes the whole dynamic and makes everyone present more interesting? That’s how I feel about other writers, other books, other thoughts – I invite them in to help me be more interesting to myself.

These poems are often quite funny, even when meditating on very philosophical subjects. You have great comedic timing. Do you consider any comedians or comedic writers influences?

I love this question. No one has ever asked me this! I immediately think of the deadpan, erudite humor of New York School poets like Koch and Ashbery, or the goofy surrealism of James Tate and Bill Knott. But I also remember a conversation I had many years ago with the poet Sampson Starkweather, where we both admitted – we could not deny – that the old SNL segment Deep Thoughts with Jack Handy must be counted as an influence. (“Anytime I see something screech across a room and latch onto someone’s neck, and the guy screams and tries to get it off, I have to laugh, because what is that thing?”)

Lately, what’s next for the Gabbert hive to look out for?

I recently finished another book of essays, a mix of personal and literary essays, in the vein of The Word Pretty, which should (knock wood) be coming out from FSG in early 2024. It’s called Any Person Is the Only Self.

As always, if you like this newsletter, please consider subscribing or checking out my recently released science fiction novel The Body Scout, which The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent” and Boing Boing declared “a modern cyberpunk masterpiece.”

Loved the interview! It's always nice to read about differerent writing routines too

lovely interview!