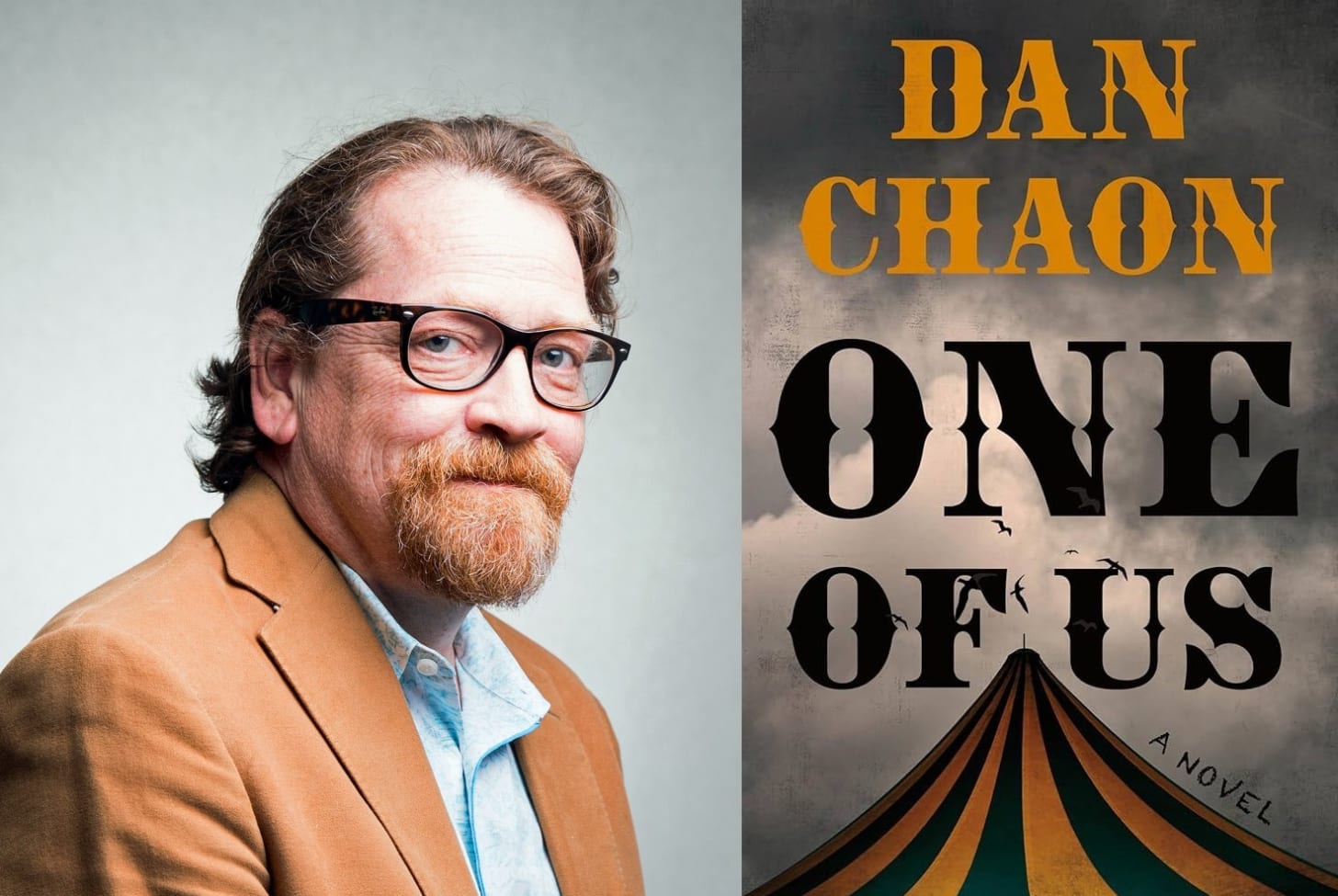

Processing: How Dan Chaon Wrote One of Us

The author on historical fiction, writing villains, and the darkness of older children's literature

On a semi-regular basis, I interview authors about their writing processes and the craft behind their books. You can find previous entries here. This week I’m excited to be talking to Dan Chaon, whose latest novel, One of Us, is a perfect October read. The novel follows twins Eleanor and Bolt who flee their murderous uncle Charlie and end up adopted by a Mr. Jengling for his traveling Emporium of Wonders where they meet a cast of memorable carnival characters like Herculea the Muscle Lady and Tickley-Feather the clown. The resulting story is part rollicking adventure tale, part dark fantasy, and party horror-tinged Western. It’s strange, captivating, and a whole lot of fun.

I spoke to Chaon over email about the historical setting, the darkness of older children’s literature, and genre expectations as a means to “slap the character (and the author) out of their reveries and push them toward action.”

One of Us is set in 1915, and I was very impressed with how the prose strikes a balance between the historical and modern. Historical fiction can sometimes risk sounding either too archaic or (more often) being filled with too many modern idioms and phrases that take the reader—at least this reader—out of the setting. I was never taken out of One of Us. The prose here is beautiful and conjures the period, as well as the setting of traveling circuses with their showmanship language, while still feeling contemporary.

How did you approach the style and language for this novel?

I’m very interested in the beauty and strangeness of words—words as sounds and words as text/image on the page—and early on in the process of writing One of Us I found myself going on these treasure-hunting expeditions, seeking out what was peculiar and unfamiliar in the argot and vernacular of that time period. Of particular interest to me were fiction writers who used idiom, and particularly those who wrote dramatic monologue-style stories, like Ring Lardner and Sherwood Anderson. Vernacular direct address was much more acceptable and popular back then—I think it seems a bit corny or stagey to us, but survives, to some extent, in stand-up comedy. I also drew on sociological work that made use of oral history, such as Joe Nickell’s Secrets of the Sideshows and a wonderfully wacky treatise called The Hobo: Sociology of the Homeless Man by Nels Anderson, which I just happened across on Internet Archive. In addition, I discovered the amazing reference book Green’s Dictionary of Slang, a truly towering achievement written over a period of seventeen years by Jonathon Green, which collects slang words from c. 1500 onward, and which I spent many, many happy hours immersed in.

Finally, I read a lot of newspapers from the early 1900s, particularly small town newspapers, and I particularly delighted in the small quirks of spelling and grammar conventions: “foot prints,” “border-line.” That kind of stuff is catnip to me.

In an interview with The Coachella Review, you said that you set One of Us in the past in part because you “just don’t want to live in 2025 all the time”—a sentiment I imagine many readers will share. At the same time, you note there are many elements of that era that “have echoes” with today. I certainly felt those echoes while reading. Did those similarities come into the text through your research? And in general, I’m curious how research informed the novel.

I didn’t set out to write much about the larger political forces at play in the world in 1915. I think WWI is only mentioned a couple of times, for example. Instead, a lot of my research focused on homely scenic detail. What did a South Dakota railroad town look like? What were people eating and wearing? What did they do for entertainment? I got more out of the Sears & Roebuck catalogue and newspaper advertisements and want ads than I got out of historical overviews.

But researching those small details would inevitably lead me to the larger stuff: the ways in which technology was transforming people’s lives, the ideas and philosophies they believed in, the way that larger forces affected the quotidian. For example, the recent scientific discovery of radiation was a source of fascination for turn-of-the-twentieth-century people, as well as misinformation and hucksterism—people were going to “curative” hot springs to bathe in uranium-tainted water and drinking “restorative” water out of radium-lined crocks, and I happened across this because I was looking for quack medicines that might be sold by a charlatan.

Many of my discoveries were accidents. I originally set a scene from the carnival performer Dr. Chui’s childhood in Rock Springs, Wyoming because I myself had lived there for a while when I was a kid and I knew that it had once had a large community of Chinese railroad workers. Then I discovered that it had been the site of a brutal anti-Chinese immigrant massacre—which I had known nothing about; it wasn’t mentioned in school, of course. And that led me to the politics of immigration and the labor movement and “big picture” material that I wasn’t intending to write about at all.

“Genre-bending” has become something of an overused term, but One of Us feels like a true genre-bending novel in that it’s in conversation with genre traditions like the Western, horror, and adventure fiction. Is genre something you think about when writing? What does it mean to you to write in a genre?

I started out as a “genre” reader as a kid—I was particularly fond of horror, fantasy and pirates—and I continue to consume a lot of genre work as an adult. As a writer, I’m drawn to genre because it provides a template for plot, a set of reader expectations that need to be fulfilled in one way or another. This is not to say that genre means “formula.” It’s more like a sonnet. You are given a kind of structural blueprint, but within those confines you can do an infinite number of different things. I find that useful, particularly because given my druthers I tend to get lost in descriptive prose and dreamy, indecisive characters who stand at the kitchen sink and gaze out the window while the dishwater gets cold, feeling vaguely melancholy or anxious. The great thing about genre expectations is that they slap the character (and the author) out of their reveries and push them toward action.

In addition to blending genres, One of Us has a wonderful blend of tones. The book is at turns elegiac, horrifying, rollicking, wondrous, poetic, and comic. The way the book moves through tone perhaps mirrors the carnival setting, where a variety of pleasures and surprises exist side by side. Is tonal variety something you were aiming for?

Tone is so tricky, because it’s not exactly objective. One issue I face is that I’m not always sure how my sense of humor translates. Back when I was teaching creative writing, I once had an extremely uncomfortable workshop experience when I began talking about how hilarious a student’s story was, and the kids looked at me blankly at first, and then with increasing puzzlement and incredulity. “Professor Chaon, I don’t think this is meant to be funny,” piped one student at last, and the rest grimly nodded. I was so embarrassed!

“Oh,” I said.

Nevertheless, as subjective as it is, I am interested in tonal effects. There’s nothing better than making a set of words that you hope will make someone laugh, or cry, or gasp, but I especially love the indefinable moments, in which several tones can exist at once. I loved writing the Uncle Charlie character because he is a loathsome monster and also, I think, very funny, and also, he has moments of poetic reflection. And all of those things can exist at once. For me, one of the things that makes writing flat is a single sustained tone. It’s like monks chanting. Monochromatic.

I am most interested in finding details and actions that can swing from one tone to another. If you can grab a moment that makes you simultaneously full of multiple emotions, that’s the Grail, man.

I wanted to ask about the structure of One of Us. The novel focuses on the siblings Bolt and Eleanor, but there are regular chapters from the perspective of their Uncle Charlie, who is trying to hunt them down, as well as stories of the various workers at Mr. Jengling’s Emporium of Wonders. Despite the roving chapters, the novel keeps the plot moving. Was this a structure you had settled on before writing or one that came about while drafting? And how did you plot the novel?

Originally, it focused on Eleanor and Bolt exclusively. I had these really basic plotlines in place: the twins are being pursued by this crazy man! And also, the twins are pulling apart in two different directions! But once I started to write about the carnival, I began to see that really it was a story of a community—and that the backstories of the various performers were not just side-hatches, but actually central to what the novel was about.

The roving POV gives us a variety of unique characters and voices, but one that stood out is the villainous Uncle Charlie. How did you get in his murderous yet somewhat ludicrous mindset when writing his chapters?

I was part of a Dungeons and Dragons group for years, and my character was a Chaotic Evil warrior named Hack Hairy-Hands, and later he was an avatar in the video game Skyrim, so I’ve embodied this sort of character before—he came to me very naturally, and at times threatened to take over the novel.

There are also elements of my dad, who I didn’t meet until I was in my mid-twenties. He was a colorful character who had a goofy verbal flair that I gifted to Charlie. “Bejabbers!” is one of my father’s exclamations. Also, “For crying out toothpicks!” which didn’t make the final cut. My dad styled himself as a charming rogue, and he was to some extent, but he was also the sort of guy who goes to a bar with the intention of getting into a fist fight for fun. The cheerful joy he took in violence was also something I gave to Charlie.

Finally, there was a bit in my previous novel, Sleepwalk, that I particularly liked. “You have to wonder about these settlers of the Great Plains,” thinks the narrator, Will. “These white people who in olden times killed the natives and laid claim to this dirt and stuck to it; who stranded their children and grandchildren with a birthright of dust. A collection of clapboard shacks with backyards full of pigweed and junked cars and abandoned swing sets and withered, thirsty trees. Was the genocide worth it?

But who am I to look down on them? No doubt in the grand scheme of things we are all the offspring of murderers. Right? If we weren’t, we probably wouldn’t be here.”

I guess Charlie is the extension of that idea.

One of Us is a very visual novel. There are action set-pieces, colorful characters, and more. Your author’s note mentions some visual inspirations, such as the films The Night of the Hunter and Dumbo. I’m curious if you used visuals in the process of writing, for example drawing characters or creating mood boards.

Most definitely. I’m sure I looked at thousand of pictures of sideshow performers and vaudeville acts, as well as many images of various deformed fetuses in jars. I went to the Circus World Museum in Baraboo, Wisconsin and took pictures of all the stuff.

The Disney films Dumbo and Pinocchio both provided details that helped me create a mood of dark innocence. I think particularly of a moment in Pinocchio when we see a set of hanging, broken puppets in Stromboli’s quarters, swaying like windchimes. Or the scene in which Dumbo is brought to visit his mad, imprisoned mother, and she cradles him. Those are images that marked me.

But the thing that inspired me the most were children’s books from the time period—which were so INCREDIBLY dark, it’s astonishing. For example, here is Gustave Doré’s illustration of “Tom Thumb,” from Perrault’s Fairy Tales:

And here is an illustration by an uncredited illustrator from a nursery rhyme book, depicting “Ding Dong Bell:”

I’m certain Charles Laughton must have been thinking of such illustrations when he was directing “Night of the Hunter.”

In any case, this kind of chiaroscuro effect was what I was trying to create in my prose:

The kind of sinister depth of a silhouette.

Throughout much of the book, it is ambiguous whether the supernatural powers of the characters were “real” in the world of the story. You give the reader reasons to believe and to doubt. It reminded me of Tzvetan Todorov’s theory of “the fantastic,” which is a type of story defined by “hesitation” between realistic and supernatural explanations for the magical. Why did you decide to make the supernatural ambiguous in the first half of the novel?

The question of how to introduce fantastical or science-fictional elements into a story has always been interesting to me, and I think I’ve been particularly influenced by Ray Bradbury’s method, which is to create first a naturalistic human drama in which the uncanny aspect is just a part of the background.

I also thought that it was a good way to develop tension between the twins. Bolt believes strongly in this psychic connection they have, and when Eleanor dismisses it as a childish fantasy, it shakes him and deepens the rift between them.

As a last question, it is often said that most writers are outsiders. Few embody the outsider more than “freaks.” Any advice for any weird outsiders who are working on their own novel?

Try to find your people.

Hunt for the writers that speak to you most, and then seek out the authors that they loved, and branch out from there. Keep reading and discovering new books.

And look for someone who you can share your work with. The ideal is to seek out readers who are on your wavelength, who like the books and films that you like, but who are not pushovers, people who have opinions. I didn’t find traditional workshops particularly useful, but I found a few friends and relatives that I trusted, and I’ve stuck with their advice for years.

And finally, try not to be attached to results.

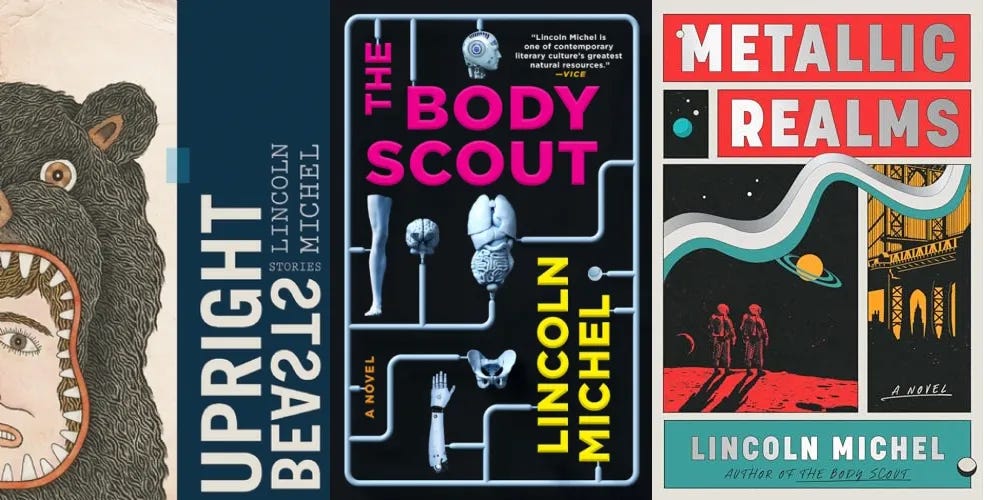

My new novel Metallic Realms is out in stores! Reviews have called the book “brilliant” (Esquire), “riveting” (Publishers Weekly), “hilariously clever” (Elle), “a total blast” (Chicago Tribune), “unrelentingly smart and inventive” (Locus), and “just plain wonderful” (Booklist). My previous books are the science fiction noir novel The Body Scout and the genre-bending story collection Upright Beasts. If you enjoy this newsletter, perhaps you’ll enjoy one or more of those books too.

I love this! And I cant express how much I understand the idea of genre expectations helping slap a character awake 😆

Awesome interview, I’ve never heard of this author but I’m definitely going to check his work out now.