On Productivity

Some thoughts on writing, writing a little, and writing a whole damn lot

When I was younger, my aspiring writer friends and I would debate “would you rathers.” Would you rather have a bestseller or win a Pulitzer? Would you rather be famous in your life and then forgotten, or obscure now and posthumously canonized? The question that got the most heated debate was: Would you rather publish a lot of books, some okay and some great, or just a couple of great books?

To me, there was never a question. I’ve always aspired to a large bibliography. My early writerly ideals were authors like Calvino, Nabokov, and Le Guin—I’d add later discoveries like Everett, Bolaño, and Butler—who published frequently while experimenting with different forms, styles, and genres. Of course, I love many authors who published only a few books. But I always wanted to produce. A lot of my friends felt—and still feel—differently. They would rather publish only the best work. “Why add more mediocre work to the world?” they told me. “I’d rather write one perfect book than a bunch of good ones.”

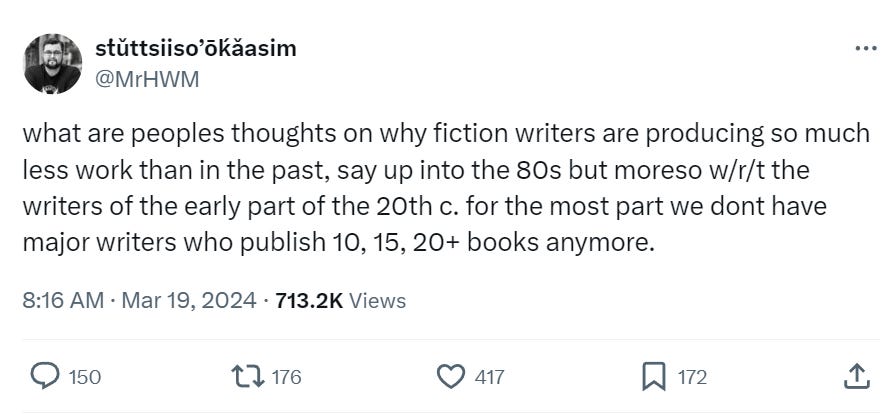

I was thinking of these old debates during an interesting Twitter discussion of productivity, kicked off by this tweet:

Although exceptions always exist, this seems right to me. Perhaps truer in the “literary fiction” sphere than the “genre fiction” sphere, although somewhat true in the latter as well. In my view, there are simple economic factors determining most of this: basically, there’s less money in fiction writing now. Part of that is declining reading rates (so book advances are lower) and part is that the tech world has swallowed up revenues online (so magazines pay less). Because writers still have to pay rent and buy groceries, they understandably turn to other sources of income. Sometimes this is other types of writing—Hollywood screenplays, ghostwriting celebrity memoirs, etc.—leaving less energy for producing books with one’s name on the cover. Often it is teaching or some unrelated field that eats up your time.

Academia also incentivizes publishing well rather than publishing a lot. University hiring committees tend to care more about prestige—awards, rave reviews, fellowships—than sales. And if one secures a tenure track job after, say, a highly regarded debut, then your economic incentive to publish might largely disappear even if your creative impulses are still there. (These were central points in the infamous “MFA vs. NYC” essay that spawned many bitter discourses.)

Of course, some genres still sell well and those tend to produce a higher number of highly productive authors. Still, even in those genres it seems we’re past the time when writers like Stephen King and Joyce Carol Oates were simply especially productive instead of absurdly, almost unbelievably productive.

Then again, there is a difference between productivity and publishing.

Many authors produce a lot of worthy material, but can’t publish it all. Because publishers don’t want to publish authors too frequently outside of the bestselling genres like (right now) romantacy, romance, and thrillers. Few publishers are champing at the bit to publish a lyrical, experimental literary novelist at a one book a year rate.

Publishers believe—and to be fair I see no reason to think they’re wrong—that having a few years between books is useful for everyone involved. It gives the publishers more time to launch books properly, gives readers time to catch up and build excitement, and those both help the author actually sell copies. An executive director for one small publisher said many publishers have a “three year minimum between books” rule:

Obviously there are exceptions—Reid notes Graywolf didn’t apply the rule to Percival Everett—and in popular genre spaces this rule doesn’t seem to exist at all. But most authors don’t tend a large number of rabid fans who will buy any book an author puts out. Time helps with sales.

What about the artistic question though? If we could publish more frequently, would that be creatively beneficial or a hindrance? There’s a popular idea that the longer someone works on a piece, the better it will be. This seems intuitive: more work = better, right? But I’m not sure history supports this. Think of the 1960s and 1970s when artists like The Beatles, Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Sly and the Family Stone, The Clash and/or [insert your favorite names] were producing now classic albums at a nearly once-a-year pace. Many of my favorite fiction writers produced their best works in very productive periods. Italo Calvino published eleven works of fiction between 1957 and 1972, plus plenty of nonfiction. Octavia Butler published five books in five years to start her career. I recently wrote about how Percival Everett has on an astounding run publishing four novels in five years.

[Editing to add: By producing “a lot,” I’m speaking of something like one book every 1-3 years. That’s a lot in the literary fiction space. In other worlds, such as the self-pub world, authors sometimes publish 5 or more books every single year! So these conversations are very different in different spaces.]

I could go on and on. Of course, there are lots of great artists who produce equally great works on a much slower timeline. Authors who publish one great book a decade and musicians who wait many years between albums. What I’m getting at here is my usual spiel, which is that it all depends on the individual artist’s process and temperament. Some artists need to spend a long time on a project. That’s the only way they can produce great work. But other artists thrive on productivity.

Productivity is generative for these artists. Ideas split hydralike into new ideas, and so on and so forth. I don’t think it is a coincidence that so many of the musicians and authors I’ve named—we could add in other artistic mediums too—are famous for hopping genres, styles, forms, and modes. For this type of artist, working too long on something can even kill whatever spark it had. Polishing diamonds into dull stones, as it were. I don’t think that Charles Dickens or Prince or [insert your favorite productive artist] would have been better if they produced less. The producing was central to the process.

At least it seems to me. And if this is true—if there are artists who creatively thrive on productivity—are we stifling them and depriving ourselves of some excellent work by not publishing them more frequently? And are we possibly stifling their careers?

But then “would you rathers” are after all just fantasies. You can’t control the market or awards committees. You can’t even entirely control your creative process, career, or life path. You can only create the best work you can at whatever pace works best for you.

If you like this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my recent science fiction novel The Body Scout that The New York Times called “Timeless and original…a wild ride, sad and funny, surreal and intelligent.”

Other works I’ve written or co-edited include Upright Beasts (my story collection), Tiny Nightmares (an anthology of horror fiction), and Tiny Crimes (an anthology of crime fiction).

As a decently prolific *reader* it drives me a little bananas when writers are ultra-productive. With them, I'm left feeling I just can't keep up, as much as I'd like to. In the genre space, authors like Adrian Tchaikovsky and Seanan McGuire have routinely published three to five books a year, and it seems they rely on relationships with multiple different publishers to make that happen. I also recently read a piece by an indie writer who argued that indie publishing allows prolific writers to circumvent the three (or one) book a year rule imposed by publishers. "Indie" + "ultra-productive" don't to me sound like a recipe for high quality writing, though, and I avoid it.

I am someone who would be a slow writer in any imaginable universe, just because that is how my brain works. But I don't think contemporary publishing's snail's pace even benefits someone like me. It was more than two full years between signing the contract for my dragon novel and it actually launching, and I was rarely in contact with my editor for much of that time -- it wasn't like I was swamped with major revisions. Imo that kind of time scale leads to dwindling enthusiasm on the publisher's side by the pub date (especially if the book was particularly timely when written) and the author often feeling pretty distant from the project by the time they have to do a ton of promotion.