Is the American Bibliography Shrinking?

Writers don't seem to be writing, or at least publishing, as much as they used to

Before this week’s Counter Craft article, I wanted to share two pieces of news. First, I have a new weird horror story in Nightmare called “The Tugwort.” Second, my novel Metallic Realms got its first trade review in Booklist. Review is for subscribers only, but here is a quote: “Exciting and tragic and funny and bewildering and just plain wonderful.” (!!) More info and preorder links here, if your interest is piqued.

Is the American Bibliography Shrinking?

As long as I’ve wanted to be a writer, I’ve wanted to write a lot of books. Others may dream of Pulitzers, film adaptations, or the Great American Novel. I’d love all of those too. But what I’ve wanted most was a bibliography. An oeuvre. To earn enough money and acclaim to allow me to write the next book, and the next, and the next. I’m not saying this is more noble than the writer who carefully crafts a masterpiece over a decade. Many of the greats wrote that way. But my artistic temperament leans in the other direction. I’m energized by productivity. By trying out new tactics and styles. The writers I’ve always held up as my artistic ideals are those like Italo Calvino, Ursula K. Le Guin, César Aira, and Percival Everett who wrote—or still write—dozens of books across a variety of genres, styles, and forms.

That I don’t have a long bibliography already is mostly my own fault. Procrastination, smart phones, distractions, etc. But my attention was caught when I read

’s Substack article “Where Are All the Young Writers?” about how my generation of writers simply aren’t publishing that much:I did a little digging to see if my perception of there not being literary career titan writers under the age of 45 matched the actual reality. I started by looking back at 10 years of the National Book Foundation’s “5 Under 35” list, from 2011-2021, so that every writer had a least a few years to have a career and so that the hypothetically oldest person would still be under 50 today. […] Of the 55 novelists, nearly half (21) would never go on to publish another book after they won this distinguishing award for being a young and promising writer. An entire generation of talented literary writers are not producing or having writing careers in the way they used to.

(Here I must disclose that Sean deLone is my fantastic editor for my forthcoming novel, Metallic Realms. I hope for future books too! But I have yet to submit any subsequent manuscripts, so nothing I say below is about him specifically.)

That statistic is wild to me. And yet also… expected? Most writers of my generation or younger seem to have short bibliographies. (Yes, generations are fake, but they are useful shorthand for different eras of publishing.) There are exceptions to the minimalist millennial oeuvre. There are always exceptions. Most of the exceptions I can think of fall into two camps: 1) Authors on very small publishers who make no money yet have the great artistic freedom small presses provide. 2) Authors on genre imprints, especially those writing series or doing IP work. There is still more of an admirable “writing is a day job” attitude in the genre world.

When it comes to the nebulous category of literary fiction, the situation seems different. I don’t want to get to in the weeds about the definition of “literary” here. Let’s just say for our purposes this refers to the kind of books that compete for literary awards (PEN awards, Pulitzers, NBCCs, NBAs, etc.) and are published on imprints dubbed literary (FSG, Knopf, Grove, Riverhead, Graywolf, Penguin Press, etc.). This includes many authors of science fiction, fantasy, and other genres in 2025. The distinction between literary and genre is perhaps less about content than ecosystem these days.

Why are literary authors publishing less? I think many of the causes are not terribly mysterious. I won’t be shocking anyone to say that streaming TV, cell phones, social media, insane politics, etc. drain our time. On top of this, authors are also increasingly expected to “build platforms” and publicize ourselves. A lot of time that could be spent writing books is instead used to post on social media, film TikToks, or, yes, write newsletters. This is all true yet seems like only part of the answer. I know a lot of authors who write more than they can publish. Even those who earn out their advances find it harder and harder to publish the next one. Publishing seems to have changed in specific ways that discourage or prevent authors from publishing as much as they used to.

Remember Back in the Day…

I thought of this whole topic again when I read Dan Kois’s interesting piece at Slate looking back at the wild phenomenon of Dave Eggers’s first book, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. The 2000 memoir had the kind of publication story that’s impossible to imagine today. A number one bestseller, Pulitzer finalist, and general phenomenon among both the literati and the general public. I missed this myself—I was a punk kid in high school who avoided anything mainstream and so it wasn’t even on my radar—but when I got to college and became interested in writing seriously, Eggers’s many tentacles were unavoidable. No matter what you think of Eggers’s novels, his creative output is staggering. Not only did he help found McSweeney’s (the long-running literary magazine, publishing house, and humor website) and philanthropic projects like Voice of Witness and 826 Valencia, but his literary output is quite impressive. In the first ten years of his career, Eggers published the following according to his Wikipedia bibliography: 7 novels, 3 short story collections, 5 children’s books (4 co-written), and 3 non-fiction books (1 co-written). Even discounting the co-written works, that’s 13 books in a decade. And that is not including 2 co-written screenplays, a photobook, and a handful of edited anthologies in addition to McSweeney’s issues.

It is impossible for me to think of a millennial writer who even approaches Eggers here. Sally Rooney reaches or surpasses his readership but not output. Only 4 books in 8 years, and Rooney is on a much faster pace than most of her peers. Both Eggers and Rooney are outliers though. Writers who get such great success out of the gate will always be able to do whatever they’d like to do.

What I worry about is whether we’re losing the interesting “midlist” authors who take a few books to break out and become “names.”

The Difficult Middle Books

Take, for example, Jonathan Lethem and Colson Whitehead. These are two authors I did read and admire. Both jumped around genres and styles, testing out different artistic ideas. While they are huge names now, they took some time to achieve that status. In Lethem’s first 10 years, he published 6 novels, 1 novella, and 3 short story collections. Lethem’s career really took off—commercially and critically—with novel #5 (Motherless Brooklyn). Colson Whitehead won some big awards early on, including the MacArthur (!), but he likewise made a commercial leap with novel #5 (Zone One, a bestseller) and then became a superstar author with novel #6, The Underground Railroad—a bestseller, Oprah pick, and winner of the Pulitzer, National Book Award, and Arthur C. Clarke awards. There are many other examples we could list here. Ann Patchett also had a breakout on novel #5, Bel Canto. Sigrid Nunez had her breakout with The Friend, her 8th book and 7th novel. Etc.

Are careers like these nurtured in today’s publishing environment? All of those authors published on big presses, sometimes just one for their whole career. Would big publishers support young authors today through interesting yet not bestselling novels like Girl in Landscape and Apex Hides the Hurt? How many millennial authors will be allowed to get to novels #5, #6, or #7 at all if they aren’t writing consistent hits? If younger authors aren’t allowed to write those interesting middle-career books, they may never get the chance to write their big successes. I’m speaking financially here, from the point of view of a publisher looking for a return on an investment. Artistically, the weirder and more experimental books are typically my favorites.

Some authors don’t need to publish frequently. Some work better carefully constructing a masterpiece over many years. Other authors with different artistic temperaments thrive on production. They need to experiment and test out new genres, ideas, and forms before they are able to write the books that make their careers.

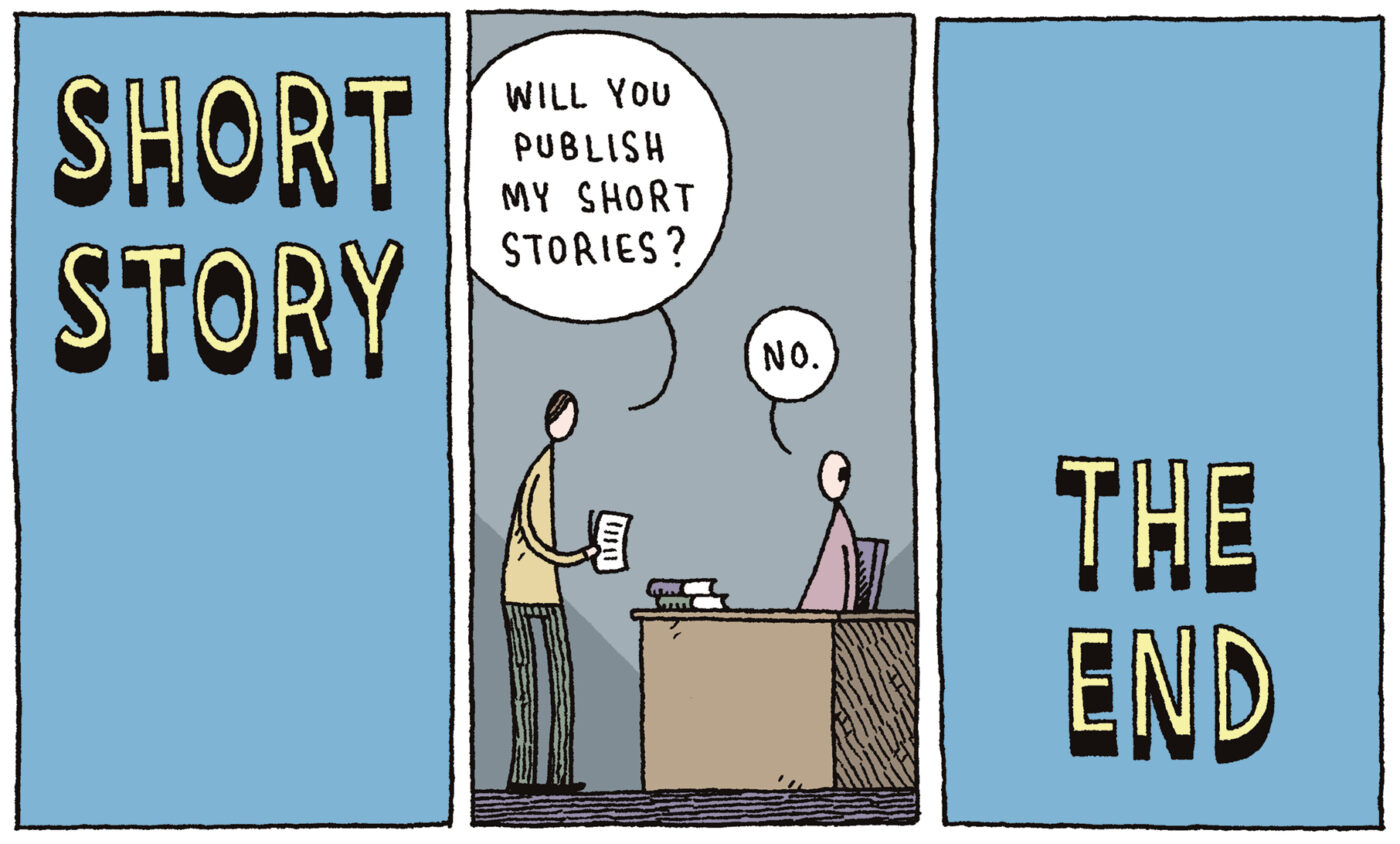

The Vanishing Collection

Another shift in the last twenty years is that big publishers—by which I mean Big 5 imprints as well as the large independent presses—rarely put out collections. It used to be common for a literary author to get a two-book deal to begin their career: a story collection to start building a reputation, and the novel to make money. Now? Big publishers tend to farm out the reputation-building work to small non-profit presses. Even if you are a decent seller, publishing a short story collection is hard. Hell, when you do see them now they are frequently marketed as “novels in stories” or even just “novels.”

Here’s another example of a career trajectory that would be hard to replicate today: George Saunders. Saunders is probably the most influential story writer of his generation. He published four short story collections, one essay collection, and one novella with Random House and Riverhead before publishing his bestselling, Booker-prize-winning novel Lincoln in the Bardo.

I can’t think of any millennial writers who were allowed four story collections before a novel. Actually, I can’t think of any millennial writers who have published four (or even three) story collections on big presses at all. Essay collections also seem to be declining, especially for fiction writers. Many older authors we may think of as primarily novelists in fact published mostly collections. David Foster Wallace published twice as many collections (half fiction, half non-fiction) as novels. Ann Beattie, Joy Williams, and many others have published more collections than novels.

I can’t necessarily blame the publishers for the vanishing collections. Financially, collections are a riskier bet. But as a lover of stories—as both a reader and writer—it isn’t the most exciting trend.

Building Buzz Takes Longer and Longer

Publishing is increasingly built around a blockbuster model where a few big hits fund everything else. Some of this may be publishers’ shortsightedness…. but much of it is simply reader tastes. Despite the early hopes of the internet as producing a “long tail” effect where culture could be spread more broadly, what has actually happened is consumers increasingly coalesce around a few huge hits. MCU movies, Taylor Swift albums, etc. The same is true in books, if on a smaller scale in terms of sales.

Across genres, publishes rely on big hits. In the always nebulous category of “literary fiction,” there is an extra issue as far as productivity goes. Despite what myths circulate online, genre fiction doesn’t necessarily sell more than literary fiction. Some genres like thrillers and (at least for much of recent history) YA sell more, but genres like science fiction and fantasy and horror don’t necessarily appear on the bestseller lists more than “literary fiction.” But. Genre sells consistently. Genre publishers know they can publish authors regularly and move copies. Literary publishing is a bit different. Books marketed as literary fiction can sell quite well but there isn’t the inherent market that promises consistent sales. Instead, the literary ecosystem needs to “build buzz” around books and publishers prefer gaps between publications. If you publish too frequently, you are told that you risk “cannibalizing your sales.”

Again, I’m not saying the publishers are wrong from a business perspective. Review space shrinks every year and readers gravitate ever-more to the mega hits. It does take more time and effort to build buzz and readership for authors today than it did 25 years ago. It does means younger writers can’t publish as frequently.

Paying the Bills by Not Publishing

Of course, hanging over all of these questions is money. This is America after all. It’s no secret that advances are shrinking alongside the midlist and review column space. Publishing pays less than it used to. Sean deLone makes this point in his article: “economic opportunities whether in academia, Hollywood, or even with toy companies suck up the literary talent and attention of the younger generation. Who can blame them? Why do something that is harder (write a novel) and pays less money than do something that is easier and pays more?”

A lot of writers I know have shifted their energies to places other than fiction writing because, well, they have bills to pay. I don’t blame any novelists for taking the first train out of novel writing, so to speak, when it is simply easier to pay the bills through speaking fees or by writing for Hollywood and TV. (Though Hollywood and TV are undergoing their own crises these days…) A lot of writers I know have also felt forced to shift efforts to other fields because they can’t sell their next books even if their previous ones did pretty well. Or their editors and agents have left publishing—the industry can be just as unstable for them as us writers—and the process of finding new ones is so time-consuming and daunting they give up.

Throughout this post I’ve been talking about bigger publishers, because those are the ones that pay. Many of the best books published today are published by small presses and micropresses. They should be commended for publishing work that would otherwise never exist. I buy books mostly from the small presses myself. Still. It is not possible to live on 1,000 dollar advances for novels that take years to write. Which means even the productive authors on those presses are not likely to be spending as much time on their writing as they’d like.

I can already feel some readers thinking “Hey, real writers write for love, not money!” and “Writing has always been hard!” Whether or not this is true doesn’t actually change my point. As a writer of weird short stories, I obviously agree there is a lot of value in writing for little to no money. But there is a zero-sum question here. We only have 24 hours in a day. And unless you are independently wealthy or funded by a spouse, then you have bills to pay. The more money you can make writing, the more time you can devote to it. The less you make from your art, the more you have to work elsewhere.

Anyway. What can one do? C’est la vie and all that. I think big publishers make some mistakes like throwing lots of money at splashy books (that frequently bomb) instead of supporting midlisters long enough for them to “break out.” But also, most of the forces at play here aren’t going to change anytime soon. Our attention is divided. Consumers gravitate to blockbusters across artistic mediums. Tech corporations have successfully siphoned off much of the profits in arts and culture. Etc.

And personally I cannot complain. I am quite happy to be publishing my third book this May. If I’m lucky, readers will enjoy it enough that I can sell book four and then book five and book six and so on. Of course, I need to write them first. It is up to me to log off and fill those pages. Hell, maybe I should do that now.

I published a first novel in 2000 with Picador. Got paid $7500. Had just come out of grad school 40K in the hole.

I had to get a "real" job, and then had a major personal disaster that took a couple of years to recover from. Agent dropped me.

If we want a robust publishing environment, writers need support. Not all of us are "energized" by the hustle. I could have written more books on a steady small income, and a place to live. Instead I spent 25 years in tech making a living, buying a house, hardening my finances and lifestyle against the crash I hoped was not coming, but now is.

Maybe if I'd had a spouse, or family support, or even any kind of encouragement and support from the publishing industry (including from my agent) I might have done it.

Just "retired" (cough cough quit my job) to finish the book I've been working on for 10 years on weekends and vacations. We'll see. I don't have much faith in the industry, but maybe I can find a new agent, and a publisher? Who knows?

I think a simple answer to this--and, sadly, to many things--is market consolidation. Most publishers are now imprints of the Big 5 (4?), and those are subsidiaries of private equity firms (SS), giant entertainment conglomerates (Harper Collins, Penguin RandomHouse), or international publishing conglomerates (Hachette, MacMillian).

What we've seen with the intense market consolidation in the film industry is that these giant corporations (like Disney) actually produce fewer films than they used to. So they gobble up the competition, the smaller fish, and then use that market power to produce fewer and fewer products.

And it seems clear that the same thing has been happening with publishing for many of the same reasons.