How to Read a Royalty Statement

The ins-and-outs of getting paid for writing a book

Before this week’s newsletter, I wanted to note that my novel Metallic Realms will be published on May 13th. Less than one month from now! The reviews so far have been excellent: “Exciting and tragic and funny and bewildering and just plain wonderful.” - Booklist. “Metallic Realms is a brilliant enigma...A hilarious book with a hard core of sadness." - MythAxis. “A riveting tale of a sci-fi writing group and its obsessive hanger-on.” - Publishers Weekly [Starred review].

If you are interested, please consider preordering (and if you read and enjoy, reviewing the novel on Goodreads or Amazon). If you live in NYC, the launch event will be at McNally Jackson Seaport on May 14th with Helen Phillips, Kevin Nguyen, and Chloé Cooper Jones. The event will be part of the McNally Jackson Festival, so RSVP before it sells out.

Now, onto the newsletter:

It’s been a little while since I wrote a publishing demystification post, and so I thought I’d answer a question that a mutual on BlueSky asked me: basically, how do you understand a royalty statement? Royalties are in one way straightforward: what your book has earned (the author’s % of sales $) minus what you “owe” (your advance $) = your royalties. But as with many things in publishing, the actual details are more complex and confusing. So, here’s a somewhat boring yet hopefully useful guide to understanding sales and royalty statements.

Some readers may say, “What’s the point of this? I’ve been told no one ever actually earns a royalty check. The only money you will ever get is your advance!” This is a myth you see repeated all over social media. It isn’t true. Books do earn out advances. Maybe not the majority of books, but enough that earning out isn’t some rare fluke and thus authors should never concern themselves with royalties. I’ve earned out all of my advances. That isn’t necessarily a brag. I’ve also never gotten a huge advance. Earning out doesn’t mean your book has been a huge hit, just that you’ve sold enough copies relative to your advance size to get a check. (A $1,000 advance is easier to earn out than a $1,000,000 advance. Yet I’d rather not earn out and get the latter. Wouldn’t you?) Anyway, authors do indeed get royalty checks so you might as well know how to read one.

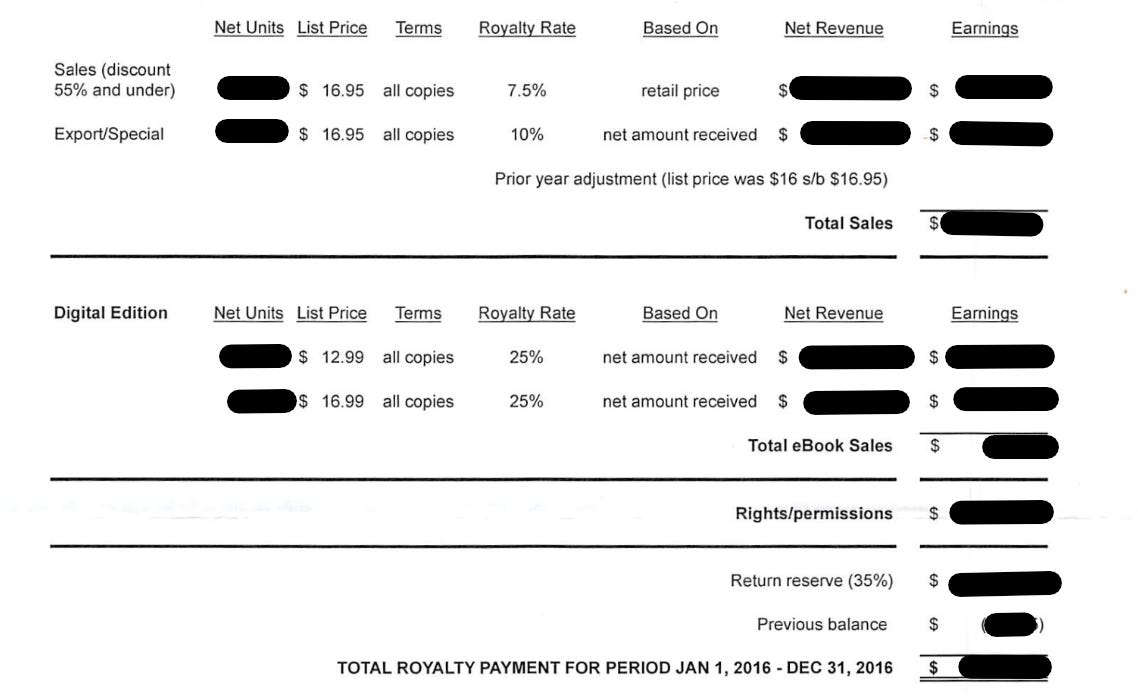

I’ll start with an sample statement as a reference. This is a redacted image of the second royalty statement from my debut short story collection Upright Beasts.

Royalties are calculated by multiplying the units sold by the list price by the royalty rate for each format. That’s your sales revenue. As you can see, the exact percent varies between formats. Hardcover, paperback, ebook, and audio can all have different rates. These rates are mostly standard, but can sometimes be negotiated for your contract.

One thing you might notice is that print book sales are based on “retail price,” meaning that if a bookstore discounts a book this does not change the author’s cut. Ebook royalties are often “net amount received” meaning you earn less from sales of discounted ebooks. (That makes sense when you think about how often publishers run $0.99 to $2.99 ebook deals. Publishers would be losing money on those otherwise.) My first story collection didn’t have an audiobook version, although I’ll note that audiobook income can be especially confusing because most audiobook earnings are part of subscription services (e.g., Audible) rather than direct sales.

After your % of sales, you add in rights/permission money—more on that below—and that gives you the total revenue. You subtract this by what you “owe” on your existing advance and any remaining return reserve and there you go. Either you’ve made money and get a check or you still “owe” money and don’t. That part, at least, is simple

You Don’t Really “Owe” Anything (Or; Advances)

An advance is money advanced to the author before a book is published. It’s your upfront money and typically broken into three or four equal payments: 1) on contract signing, 2) on manuscript delivery and acceptance, 3) on publication, and 4) one year after initial publication. You do not earn any more money unless you sell enough to “earn out” your advance.

Let’s say that a publisher pays you $25,000 dollars and (for simple math) let’s say your royalty rate is $1 dollar per book. That means you wouldn’t earn a royalty check until you’ve sold 25,001 copies of the book. Obviously the actual math is more complicated than one dollar per book, given the different royalty rates for different formats and such, but you get the point.

I’m putting “owe” in scare quotes because—unless you got scammed—an author never pays back their advance on a published book. You may owe your advance back if you fail to ever turn in the manuscript. But you never pay money back merely because a book doesn’t sell as many copies as the publisher (and you) hoped. You just won’t get more money. Think of it like “guaranteed money” in a sports contract, if that helps. Even if the team benches or cuts you, you keep that cash.

Earning Out Isn’t Just About Books Sales (Or; Rights/Permissions)

Here’s a fun fact: it is possible to earn out a book contract without ever selling a single book. Seriously. It happens.

How is that possible? Well, see the “rights/permissions” line on my royalty statement above. Publishers don’t only make money by selling books. They also make money by selling rights and/or permissions to other publishers. A publisher might sell “first serial” rights to a magazine to publish an excerpt from your book. Or a publisher might sell the audiobook rights to an audiobook maker or sell the rights to sell your book in another country or translate it into another language. The publisher takes a cut of these sales but the majority of the money comes back to the author.

Publishers will normally seek your input on these deals. You could veto if you didn’t (e.g.) want your book sold in specific country for some reason. But rights and permissions are a big part of how authors and publishers earn money.

The specifics of what rights a publisher can sell will vary by contract. Typically, your agent will ensure you keep film/TV adaptation rights. These days, almost any publisher will insist on getting audiobook and ebook rights. But whether the publisher gets “world rights” (rights to all languages), just English-language rights, or just North America distribution rights, etc. is up to your agent and publisher to hash out during contract negotiations. What’s advantageous to you, the author, will depends on your situation. If your agency is quite good at selling foreign rights, then you probably want to keep those and let your agent sell them. If the agency isn’t equipped to sell foreign rights, well, you probably want to let your publisher sell them.

But, let’s say you sold a publisher “world rights” to your novel for a $20,000 dollar advance. If the publisher sells foreign rights to France, Italy, Japan, and Brazil for $5,000 each and audiobook rights to Audible for $7,000 then, well, you have earned out your book before it is even published.

How Books Are Sold and Not Sold (Or; Returns)

In the case of the post that prompted this article, the writer was surprised by how many books they’d “sold” for the first royalty statement. Then surprised by all the “returns” in statement number two. Returns are standard in publishing, if unusual in retail. First understand that publishers don’t really sell books to readers. They sell to retailers aka bookstores and online stores. This is common business practice. Most candy makers or whatever sell to retailers too. What’s unusual is that publishers allow returns. If a store can’t sell the candy they bought, they don’t return it to the candy factory for a refund. But for various historical and economic reasons, publishing allows returns of books.

I won’t get into the various pros and cons of this model. I’m just stating the reality. That’s why I put “sold” in quotation marks above. Books that are marked as sold on a royalty statement might not actually be sold.

In my sample statement, there is a line that says “Return reserve (35%).” This is an amount the book earned that the publisher is holding to cover the potential loss from returns. If the books aren’t returned, you get that money on subsequent statements. Some publishers might not hold a % in reserve and might instead give you the credit now and then put debits on future statements. Returns are typically only a thing for the first year or so of publication. That’s when bookstore might “overorder” a large amount and sell less than expected. After the launch, bookstores tend to buy smaller amounts they know they can sell.

And That’s More or Less All You Need to Know (Or; the Bottom Line)

The last thing to note here is the royalty period. My sample royalty check covers an entire year. My second book, The Body Scout, was published on a Big 5 imprint that uses 6-month royalty periods. So, I get two a year from them. Or, to be technical, my agency gets those statements. They take their cut and send me the rest.

And that’s basically all you need to know.

There are a lot of nuances of rights/permissions and format royalty rates, but those will be built into your contract before publication. Your specific royalty statement might have slightly different wording. It might include more or less information. My Hachette royalty statements are 10 pages long, starting with a topline summary and then breaking down each part page by page.

But these are how royalty statements work. You have your credits (royalty earnings + rights/permissions sales) and subtract your debits (any remaining advance $ + returns and/or return reserve) and that equals the amount you’ll receive.

Hopefully, that number is a positive one and you can now go out and buy a lobster bedazzled with diamonds and stuffed with a glass of champagne filled to the brim with cocaine-coated caviar. Or, more likely, a cup of coffee and a sandwich.

Though, if you’d like to help me buy a metaphorically lobster-diamond-champagne monstrosity then you can buy short story collection Upright Beasts, my science-fiction noir novel The Body Scout, or preorder my out-next-month (!!!) satirical-autofiction-meets-space-opera novel Metallic Realms.

The never earning an advance myth needs to die. I've earned all my advances so far except two (my eleventh novel is out this year). One took seven years to earn out while for others they earned out by the second statement. It's very different having an advance of $5,000 than getting $500,000. Odds are you'll see royalties much faster when there's a low advance but as you mention, if you are lucky enough to make $500,000 that's not chump change and even if your book only makes you $250,000 in royalties that means the publisher took a gamble and overpaid you. Or not. Many things happen during the lifetime of a book. We're rejacketing one of my novels (a steady, respectable seller that nevertheless is not my most famous or profitable title) for sale next year because trends have changed and it might have a second life with a different cover.

I'm a lonely voice in the wind on this topic, but the whole mindset of "get the biggest advance you can, don't worry if the publisher is overpaying you, you'll never have to pay it back" is really IMO destructive to the larger project of building a truly sustainable publishing ecosystem. Every book that doesn't earn out its advance makes a publisher less willing to take a risk on the next project. It drives complacency and a herd mentality at the P&L level. Smaller advances, aka "bad advances," which offer a guaranteed annual (or biannual) payment to authors on the back end, help build more diverse and risk-friendly publishing. Like, no other industry works like this! To use the candy example: why would you expect a buyer (publisher) to pay $500,000 up front if the seller (author) was only able to deliver $250,000 worth of candy? Would you ever buy that candy again? Probably not. Lower expectations on the sales end set so many more people up for success.

Anyway, just the POV of a publisher :)