Gabagool and Malpropisms: Dialogue Lessons from The Sopranos

Some thoughts on linguistic errors in fiction and life

I’ve been slowly working my way through a rewatch of The Sopranos and remain in awe of the show. Despite debuting over 20 years ago, it still feels like a breath of fresh TV air. I think the reason is tone. The Sopranos is a show that feels full of life. Yes, it’s a mob drama with lots of violence and intrigue, but there’s also a huge amount of love, small talk, lightness, surreality, and humor. The Sopranos is adept at moving between tones. Most TV dramas of the last 10-15 years have been remarkably humorless and monotone, at least to me. They might have a few jokes now and then, but from the cinematography to the soundtrack the tone is one of Very Serious Stuff. Many of them are good, some even great, but they all feel a bit dreary to me. A bit lifeless.

(The recent shows that feel closest to The Sopranos in their ability to mix tones are half-hour comedies, like Bojack Horseman. Although Succession is a rare hour drama exception.)

One particular aspect of craft The Sopranos excels at is dialogue, and a notable feature is the errors. The characters are constantly speaking in malapropisms, mangled idioms, and mispronunciations. They mishear things or misquote each other. It happens so much it feels like a distinctive feature of the show. I can’t think of a single other TV show that deploys so many errors in dialogue.

If you don’t know, a malapropism is when you accidentally substitute a similar sounding word or phrase for the correct one. Some Sopranos examples:

Tony: “I was prostate with grief.”

Little Carmine: “There’s no stigmata connected with going to a shrink.”

Christopher: “Create a little dysentery in the ranks.”

Jonny: “She's an albacore around my neck.”

Sometimes the linguistic errors on The Sopranos are less malapropisms and more half-remembered idioms or terms:

Tony: “Revenge is like serving cold cuts.” (Dr. Melfi: “I think it’s ‘Revenge is a dish best served cold.’” Tony: “What did I say?”)

Christopher: “Keep your eye on the tiger, man.”

Little Carmine: “If there is one thing my dad taught me, it is this: a pint of blood costs more than a gallon of gold.”

Paulie: “She was in the hospital unit for an hour-and-a-half with nervous bowel syndrome!”

Tony: “Water over the dam.”

Little Carmine: “You’re at a precipice of an enormous crossroads.”

Perhaps my second favorite bit of dialogue in all The Sopranos occurs when Tony tries to steal Dr. Melfi’s insight as his own when attempting to get his mother to go to a nursing home. It takes place over two scenes:

1.

Tony Soprano: Well, we were looking at Green Grove.

Dr. Jennifer Melfi: It’s a beautiful facility. It’s more like a hotel at Cap d’Antibes.

Tony Soprano: Yeah. But to her it's a nursing home.

Dr. Jennifer Melfi: Well, she needs to be made to see the distinction. That in fact, she's embarking on a rewarding chapter. I know seniors who are inspired. And inspiring.

2.

Tony Soprano: Green Grove is a retirement community! And it’s more like a hotel at Captain Teeb’s!

Livia Soprano: Who’s he?

Tony Soprano: A captain that owns luxury hotels or something, I don’t know. That’s not the point. The point is, I talked to Mrs. DiCaprio over there and she says she’s got a corner suite available with a woods view. It's available now, but it’s gonna go fast.

[they fight for a bit]

Livia Soprano: Then kill me now. Go on now, go into the ham, and take the carving knife and stab me, here, here, now, please! It would hurt me less than what you just said.

Tony Soprano: You know, I know seniors that are inspired!

And my absolute favorite bit of Sopranos dialogue, which occurs when Tony is calling Paulie but the reception is bad and he can’t quite hear.

Christopher’s delivery of “his house looked like shit” is just perfect.

The use of malapropisms and other linguistic errors for buffoonish characters is an old theater tactic dating back to Shakespeare and before. The term itself comes from the 1775 play The Rivals by Richard Brinsley Sheridan, in which Mrs. Malaprop says things like “he is the very pineapple of politeness.” You give your dumbest, most pretentious, or most clownish character these errors to let the audience know what a dunce they are.

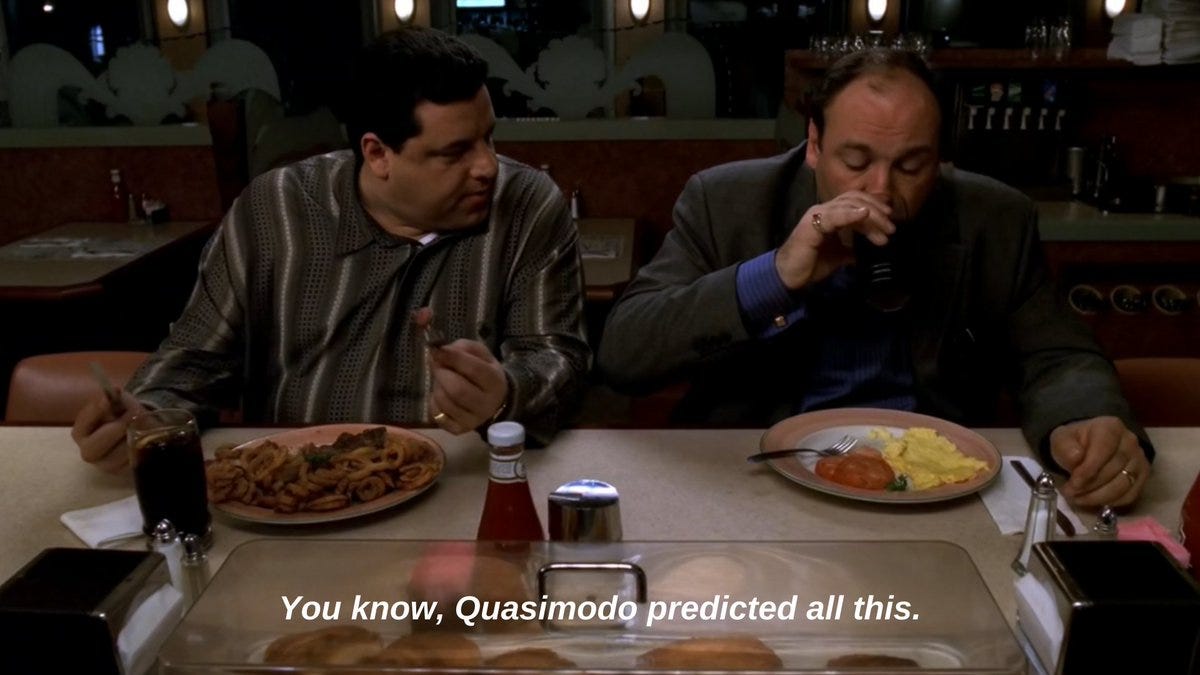

However, one thing I love about The Sopranos is that it’s not just the clown characters who speak this way. It’s all of them. That’s not to say that The Sopranos doesn’t use the errors for pure comedic effect with the more clownish characters, such as the classic post-9/11 scene where Bobby says

The full scene is worth watching:

But characters like Tony, who no one would call stupid, speak this way too. It highlights how they are street-smart-but-not-book-smart types, of course, but it also gives them a real sense of life. These types of linguistic errors happen all the time, more or less daily. And they’re more common than ever in the age of autocorrect and predictive text errors.

They’re also extremely memorable, in both fiction and real life. I’ll never forget a time two of my students asked me to settle a debate about whether the phrase “in lame man’s terms” was correct in one of their papers. Or when my phone autocorrected “are we doing something tonight?” to “are we dung sunbathing tonight?”

(Language-based memes, such as those on Twitter, frequently emerge from malapropisms or other errors. Some bit of language is distorted or mistyped and then the weirdness of it makes it propagate across the web.)

This newsletter is about prose fiction writing, and so watching The Sopranos made me think about malapropisms and other (intentional) linguistic errors in fiction. Malapropisms are much harder to pull off in fiction than plays/TV for obvious reasons. An actor’s performance can make it clear that an error is intentional on the part of the writer, but in prose if I type “it was the pineapple of success” a reader might easily think it was a typo that got missed it proofs. Then the writer is the clown instead of the character. I spent a little time Googling examples of malapropisms in literature, but the only ones I could find were from plays or else novels with child narrators.

That doesn’t mean you can’t deploy these errors in fiction though. You just need some to make sure the reader understand the error is intentional. One way I’ve done this in my own writing is pretty simple: have another character correct the speaker.

Here’s a passage from my story “The Yellow Spark of Clarity” (published in NOON, but not online):

[The doctor] said that she had a tumor in her brain that was the size of a grape.

“That’s not very big,” she said, rubbing the rind of her scalp.

“A grapefruit is quite large for a tumor,” he said.

“Ah, I thought you had said a grape fruit, not a grapefruit.”

The doctor gave her a sour look.

In one of my stories, “Dark Air,” I made a typo in the draft that I found funny enough that I simply left it and incorporated it into the story:

“We’ll sneak down that slope and make our way back to the road,” Iris said. “Then we’ll come back with police and guns and fucking rapid dogs.”

“Do you mean rabid dogs?”

“Both!”

“Sure,” I said. “Okay. That’s a plan.”

For me at least, these moments are pretty funny. But they’re also humanizing, and character appropriate. (In “Dark Air,” Iris is crazed with terror and anger after discovering a monstrous secret.) I picked these examples from my own writing because, as I said, I couldn’t find prose fiction examples easily online. If you know any good ones, please post in the comments!

But I suppose the lesson here is to embrace a bit of messiness in the way your characters speak. Life is messy. Our words are frequently mangled. Our speech confused. Shouldn’t fiction reflect that?

Okay, now I’m off to watch another episode with a bowl of fucking ziti and a plate of gabagool.

In one of P.G Wodehouse stories he has Bertie refer to someone as being ‘ as rich as creosote’.

I love these play on words...fabulous!

You might like Anne Garreta's 'In Concrete,' translated by Emma Ramadan. Lots of fun. "A riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enema."

https://www.europenowjournal.org/2021/04/01/in-concrete-by-anne-f-garreta/